Japan History: Sanada Yukimura

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Sanada (Yukimura) Nobushige was one of the greatest samurai of the Sengoku period. Second child of Sanada Masayuki and younger brother of Sanada Nobuyuki, he was never called "Yukimura" during his lifetime, since his real name was Nobushige. It seems that Yukimura was obtained at the end of the Edo period. Known as "Crimson Demon of War" for his blood-red banners and red armor, he was also recognized as "the greatest warrior of Japan" and even "The last Sengoku hero" by his peers.

As a young man, he was sent by his father as a hostage to the Uesugi clan in exchange for Uesugi's support against the Tokugawa. The father who later sided with Toyotomi Hideyoshi, as Uesugi had done, allowed him to return home to Ueda.

Sanada Nobushige served Hideyoshi directly. His first wife, Aki-hime, was the daughter of Otani Yoshitsugu even though adopted by Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Nobushige had seven daughters and three children with four wives, the last was born two months after his father's death.

photo credits: samurai-world.com

Ueda Castle, built in 1583, was the home of the Sanada clan. The fact that it was well built was first tested in 1583 when the castle resisted the attack of a numerically superior Tokugawa force. The defeat would have been embarrassing for the Tokugawa in the future. Another similar siege of Ueda Castle in the 1600s at the time of the Battle of Sekigahara also saw Tokugawa Hidetada, son and heir of Ieyasu, who led his army along Nakasendo, strategically important. Along the way, he stopped and besieged Ueda Castle. Although there was a great distance from the battlefield of Sekigahara, events at Ueda Castle would have almost destroyed the intentions of the Tokugawa legions. The Sanada resisted long enough for Hidetada to arrive late to the battle itself, depriving Tokugawa of about 38,000 men. Nobushige commanded only 2,000 men inside the castle.

Sanada Masayuki and his son Nobushige kept Ueda's castle as an ally of Western forces, however, Sanada Nobuyuki, was fighting for the Tokugawa. This ensured that at least one member of the Sanada family would be among the winners, regardless of the outcome. This was clearly a plan to preserve the family name. Following Sekigahara, Nobushige and his father were deprived of their domain and exiled to the holy mountain, Koya.

Photo Credits: tozandoshop.com

14 years after Sanada's father and son were sent into exile, Nobushige would rebel against the Tokugawa again during the winter siege of Osaka, and again the following year in the summer campaign. Nobushige had built a crescent-shaped fortress in the southwestern corner of Osaka Castle, known as Sanada Maru. The fortified outpost was surrounded by a wide, deep and dry moat. The earth of the moat was piled up inside, and along the top of this embankment, there was a simple two-story wooden wall, with platforms at regular intervals. Apparently, the Sanada Maru was armed with cannons along the walls. Sanada Nobushige and about 7,000 men repeatedly repulsed around 25,000 Tokugawa allies. Sometimes the Sanada samurai left the borders of the Sanada Maru to counter the enemy troops.

The following year, during the summer siege of Osaka, Sanada Nobushige commanded the right flank of Toyotomi's forces. On June 3, despite being completely exhausted from the battle against Date Masamune's forces, Nobushige and his men had returned to Osaka Castle to find the 150,000 Tokugawa men preparing to make one final assault. Hoping to catch them off guard and destroy their formations, Nobushige sent his son, Daisuke, to instruct Hideyori to look for opportunities to get out of the castle and attack the Tokugawa.

photo credits: pinterest.it

However, at the time of the attack, Hideyori appears to have lost control and failed to launch a counterattack that could have reversed the siege. The Sanada troops were overwhelmed. Seriously wounded in the fierce battle against Matsudaira Tadanao who had pledged him for most of this day, from 12 to 17, Nobushige sat under a pine tree in the Yasui Shrine grounds, unable to continue. When the wave of enemy forces approached, he calmly said his name, and saying that he was too tired to continue fighting, he allowed a Tokugawa samurai named Nishio Nizaemon to take his head. Sanada Nobushige was 47 years old. The news of his death spread rapidly and the morale of Osaka's troops fell.

The name Yukimura was known throughout Japan due to its fearless fighting.

Shimazu Iehisa of Satsuma praised Yukimura, writing "Sanada was the greatest warrior in Japan, stronger than any warrior in the stories of ancient times. The Tokugawa army was half defeated. I say this only in general."

A statue of the weary warrior is now found under the second-generation pine tree in the ground of the sanctuary.

photo credits: samurai-world.com

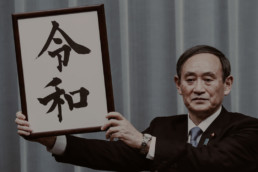

Japan Modern Culture: 令和 ReiWa, the new Era

令和: ReiWa, the new Era

Exactly one month ahead of Prince Naruhito's accession to the throne, Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga announced the beginning of the new Era for Japan.

Reiwa, formed by the kanji 令 (rei) "auspicious", "ordered" and 和 wa "harmony", "peace", reflects the spiritual unity of the Japanese people, because "culture is born and nourished when people take care of each other lovingly" explained Prime Minister Shinzo Abe immediately after the announcement.

photo credits: asia.nikkei.com

Time passes following the Era of the Emperor

In the Japanese culture, the periods of time throughout history are subdivided according to the system of "eras", gengō (元号): it involves the use of two kanji that represent the hopes, ideals and good intentions for the period to come, followed by the number from the year of the emperor's mandate. According to this system, from 1989 the current era is Heisei 31 (平成31), or the 31st year of the Heisei Era (31 years of "achieving peace" under the guidance of Emperor Akihito). From May 1st, 2019 we will be officially in the Reiwa Era (令和1 - Reiwa 1).

photo credits: tg24.sky.it

The roots of Reiwa

Unlike all previous eras whose names were inspired by Chinese literature, Reiwa has its roots in Man'yōshū, 万集 "The Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves", the oldest collection of Japanese poetry that has survived till today. The authors belong to all walks of life: members of the imperial family, peasants, soldiers, artisans and monks. This choice breaks an over 1300 years old tradition and has a highly symbolic value for Modern Japan. We are wishing for an era of hope and unity and, above all, an era aimed at the preservation of nature. Reiwa will face a path aimed at harmony and to give strength to a nation that in the course of history has always raised up with pride in every adversity and that has never been pulled back.

But how was this name decided?

The choice was made between a list of 30 proposals prepared by Japanese and Chinese literature and history experts appointed by the government for this important task. The traditional procedure requires the Government to make the final choice in a cabinet session, after which the chosen name is revealed to the Emperor in office and he prepares the decree for the proclamation of the new Era.

photo credits: kelo.com

Naruhito, Emperor of the Throne of Chrysanthemum

First born of the current Emperor of Japan Akihito and Empress Michiko, Naruhito (皇太子徳仁親王) became the crown prince to the throne following the death of his grandfather, Emperor Hirohito in 1989. Known for his countless charitable works and a series of absolved imperial functions, he will become the 126th Emperor of the Throne of Chrysanthemum (the oldest ever interrupted monarchy in the world) on May 1st, 2019 following the abdication of his father on April 30th, 2019.

The blank pages of a new beginning

The word Reiwa is so full of serenity, even in its pronunciation! The harmony, the peace, the balance that characterize a the people of a nation like that of the Rising Sun thus finds its fulfillment. Just a few days ago, I had a fixed idea in my mind: "a new beginning", I even wrote a thought entitled "Start of a new chapter", and having woken up with the announcement of this new Era, shook me positively. Furthermore, after hearing Prime Minister Abe's speech, my heart was filled with hope. I like the proposal for greater openness to work for those coming from abroad and I believe that this can bring a prosperous future for Japan worldwide.

The spirit of cohesion, solidarity and peace may seem an utopia, but it must start from the small things, from us and then spread like the waves produced by a pebble falling into the water.

Japan Tradition: Saigō Takamori

photo credits: jpninfo.com

Saigō Takamori (1828-1877) is remembered both for his important role in the Meiji Restoration which overthrew the shogunate in 1868 and for his failed rebellion against the new government less than a decade later. Although he died a renegade, a government pardon rehabilitated his reputation and 150 years after the Meiji restoration, the spotlight is again on the last samurai.

Saigō's rise to power began in 1854 when he was recruited by Shimazu Nariakira, the daimyo of the Satsuma domain (now Kagoshima prefecture), to accompany him to the capital of Edo (now Tokyo). As a low-ranking official, Saigō was involved in bridge construction projects and roads. He managed to capture Nariakira's attention with a series of memoranda on the agricultural administration that he submitted to the provincial government. Officially he was employed in Edo as a gardener, but his duties went beyond plants. While in the capital, Saigō made contact with the main personalities who opposed the shogunate. The outdoor work offered a comfortable cover for Nariakira and Saigō to meet and talk, avoiding the obstacles they would face due to their large difference in rank.

photo credits: yabai.com

Saigō quickly built a network of loyalists from Mito (now Ibaraki Prefecture) and other domains. He won the trust of Nariakira with his simple and emotional nature, and over time the daimyo came to look for the opinions of the younger people. However, the situation began to change from 1857 when Abe Masahiro died. He elderly shogunate adviser who had helped ensure the succession of his close friend Nariakira as Satsuma daimyo. Nariakira himself died the following year and the power in Satsuma passed to his younger brother Shimazu Hisamitsu. Meanwhile, the conservative politician Naosuke had taken effective control of the shogunate, launching an important crackdown on the reformists.

Suffering from the loss of Nariakira and facing difficult political prospects, Saigō was determined to follow his teacher to the grave but was persuaded by Gessho, the chief priest of a Kyoto temple, to flee with Satsuma. However, once there, they threw themselves into the sea in Kagoshima Bay and Gessho drowned, but Saigō miraculously survived.

Over the next five years, Saigō suffered periods of exile on the islands of Amami Ōshima and Okinoerabujima. On Amami he was given some freedom and married a local woman. However, After a brief respite on his return from Amami, he was again exiled to an island after angering Hisamitsu. This period of imprisonment became an opportunity for serious reflection on his life and shaped his personality as a caring man of firm principles.

Iechika Yoshiki, Saigō’s biographer and researcher, argues that, unlike most people, he was not afraid of death. Having lost many people he loved and respected, including his parents, Nariakira and Gessho, he was not terrified of dying and saw it as a way to be reunited with his loved ones.

photo credits: nippon.com

Iechika says that Saigō believed that heaven had spared his life for a reason and that he would live to complete his divine call. This philosophy is linked to his famous motto “keiten aijin”, which means "Respect the sky and love people". According to Saigō, the questions of life and death were above human consideration and had to be left entirely to fate.

In 1864 Saigō reconciled with Hisamitsu and returned to the Kyoto political center as commander of the Satsuma army. After rejecting the anti-shogunate forces from the Chōshū domain (now Yamaguchi Prefecture) while attempting to enter the city, he was promoted to the rank of high officer. The event, known as the Hamaguri Gomon incident, was Saigō's first battle experience with an army. The same year, he became chief of staff of the shogunate army sent to punish Chōshū. In 1866, however, Satsuma and Chōshū entered an alliance mediated by Sakamoto Ryōma. Saigō took charge of the opposition forces that would eventually become soldiers of the new Meiji government.

In 1864 Saigō reconciled with Hisamitsu and returned to the Kyoto political center as commander of the Satsuma army. After rejecting the anti-shogunate forces from the Chōshū domain (now Yamaguchi Prefecture) while attempting to enter the city, he was promoted to the rank of high officer. The event, known as the Hamaguri Gomon incident, was Saigō's first battle experience with an army. The same year, he became chief of staff of the shogunate army sent to punish Chōshū. In 1866, however, Satsuma and Chōshū entered an alliance mediated by Sakamoto Ryōma. Saigō took charge of the opposition forces that would eventually become soldiers of the new Meiji government.

In January 1868, the imperial loyalists led by Satsuma and Chōshū proclaimed the restoration of power from the shogun to the emperor. The resistance of the shogunate supporters triggered the Boshin war later in that month. Although the conflict dragged on until the following year, a key victory for the Meiji troops came with the surrendering of Edo Castle in the spring of 1868. With the city and nation in danger and fighting in Edo, Saigō entered the stronghold of the shogunate with only a handful of followers, wanting to try negotiation. Surrounded by enemy soldiers, he faced the prospect of murder. The discussion and cooperation between Saigō and the leader of the shogunate Katsu Kaishū led to the peaceful delivery of the castle, as a "bloodless delivery".

photo credits: nippon.com

In Japan, Saigō Takamori, Ōkubo Toshimichi and Kido Takayoshi are considered the three great figures of the Meiji Restoration. However, according to Iechika, Saigō's success at Edo Castle was something the other two members of the trio could never have achieved. He claims that without Saigō, the Meiji Restoration would never have happened and that people today see the event favorably because of this. On the contrary, if the movement had caused a bloody civil war, it is likely that public sentiment would have been very different. Although Saigō was not the astute politician that Ōkubo was, he had a love and a spirit that the other could not match.

In 1871 Saigō joined the Meiji government and in 1873 he became an army general. However, he resigns a few later after losing a debate about his support for a military expedition to Korea. He returned to his home in the prefecture of Kagoshima, where he spent his time cultivating and hunting. However, In 1877, he was convinced to lead an army of dissatisfied Samurai in the Satsuma rebellion. Driven by government forces in the battles on Kyūshū, the army reached the last position at Shiroyama in Kagoshima. Saigō committed suicide after his soldiers were defeated. He was 49 years old.

Saigō is the likely inspiration for Katsumoto Moritsugu - played by Watanabe Ken in the 2003 film The Last Samurai. The film complains of the passage of bushidō (the way of the Samurai) through Katsumoto, as noted by the Civil War veteran Tom Cruise, Nathan Algren (the character has no direct historical equivalent).

Saigo's association with traditional values in a modernized Japan is why he was called "the last Samurai". Just 12 years after his failed rebellion, he was pardoned by the Meiji government and in 1898 a statue of Saigō and his dog was erected in Tokyo's Ueno Park. Almost a century and a half after his death, it remains a popular historical and cultural icon.

photo credits: madmonarchist.blogspot.com

Japan Tradition: Hinamatsuri

photo credits: mcasiwakuni.marines.mil

Doll’s Day

There is a special celebration held annually on the third day of the third month in Japan known as Hina-matsuri (雛 祭 り), also known as Doll’s Day or Girl’s Day. During this celebration, the misfortunes of girls are transferred to the dolls and the family members pray to the gods for their daughters’ good health and beauty.

This festival dates back to the Heian period (1650) and in Japanese culture, dolls have always been believed to have the capacity to contain evil spirits. During the Hina-Nagashi (雛 流 し, The floating doll) ceremonies, straw dolls will be placed along the course of a river to take the evil spirits away with them. This ritual is still carried out in some parts of Japan.

photo credit: monchhichi.net

The Dolls of Hina-dan (雛 壇)

The hina-dan is a platform of 7 steps covered by a red carpet with a rainbow stripe at the bottom, called hi-mōsen. The hina ningyo, ornamental dolls passed from generation to generation, are placed on this hina-dan.

On the first step, the highest step, are the dolls representing the imperial court of the Heian period, the position of emperor and the empress, behind them a small golden screen and two lanterns of paper or silk on the sides.

On the second step there are three court ladies serving sake and separated by two small round tables (takatsuki), on which seasonal sweets are displayed.

On the third step there are five male musicians who are arranged from right to left and based on the instrument they hold in this order: a musician seated with a small drum, a standing musician with a large drum, a standing musician with percussion, a sitting player with the flute and, finally, a singer seated with a fan in his hands.

On the fourth step there are two ministers: the younger is placed on the right, the elder on the left. Both of them are equipped with bows and arrows while separated by takatsuki.

Three samurai, protectors of the emperor and the empress, are placed on the fifth step. They each hold a rake, a shovel, and a broom with respective expressions of weeping, of laughter, and of rage.

On the sixth step there are the objects that the court uses inside the building.

On the seventh and final step, the lowest tier, are the objects the court uses when they are far from the building.

photo credit: trend-blog-site.com

Between kimoni, hishi-mochi and amazake

During the festival, girls wear their most beautiful kimonos or dress up like dolls. There are numerous themed parties where shirozake, a special sweet and non-alcoholic sake based on amazake (甘 酒, a sweetener obtained from the fermentation of rice), arare (あ ら れ, crackers composed by glutinous rice and flavored with soy sauce) and the traditional sweet of Hina-matsuri, hishi-mochi (菱 餅 ひ し も ち) are served.

Hishi-mochi is a cube-shaped glutinous rice mixture made up of three colored layers. Each layer holds special meanings. Green represents the grass and symbolizes health; white represents snow, a symbol of purity; and finally, rose represents the plum blossoms fighting malignancy. Together these three colors indicate the arrival of spring, when the snow melts, the grass grows and the plum blossoms start to bloom.

Japan Traditions: Wakakusa Yamayaki Matsuri

One of Japan's most famous matsuri is the Wakakusa Yamayaki Matsuri held in the city of Nara on the fourth Saturday of January.

photo credits: matsuritracker on flickr

Le Origini

On the top of the third hill of Mount Wakakusa we find the Uguisuzuka Kofun, a keyhole-shaped tombstone.

Legends say that in the past if the mountain was burned by the end of January in the new year, it was possible to repel deaths returning from their graves. On the contrary, if the mountain was not burned by the end of January, a big period of misfortune layed before the city of Nara. As a result, the stories tell that people passing by Mount Wakakusa began to ignite the mountain without permission.

photo credits: smartus & matsuritracker on flickr

Following this, there were some incidents where the fire from Mount Wakakusa came to approach the boundaries of the Todaiji and Kohfukuji temple repeatedly. Because of this, in December 1738, the Nara magistrate's office (Bugyosho) prohibited people from burning the mountain. However, the arson fires continued at the hands of anonymous people and on some occasions approached the nearby cities and temples. To avoid similar dangers, the city of Nara established a rule to allow people to burn the mountain with the participation of representatives of the Todaiji and Kohfukuji temples along with the Nara Bugyosho at the end of the Edo period.

photo credits: toshimo1123 on flickr

The Yamayaki festival (burning mountain) comes from superstitions to calm the spirits of the dead at the Uguisuzuka Kofun located at the top of the mountain, so the Yamayaki could also be considered as a moment of service in memory of the dead.

Modern history and present day

Since 1900, there have been a series of changes related to Wakakusa Yamayaki Matsuri. Firstly, the time was shifted from day to night and even its date moved to 11 February (Day of the Empire), although during the period of World War II, the celebrations were held during the afternoon. Later, in 1910, the organization passed into the hands of the prefecture of Nara.

photo credits: karihaugsdal on flickr

After the end of the war, the Yamayaki once again became an evening event together with a fireworks display of over one hundred fireworks.

During the fifties, the date of the Yamayaki was moved to January 15, the "Coming of Age day", while in 1999, due to the implementation of the so-called "Happy Monday System Act" (law that moved some public holidays on Mondays) , the festival was celebrated on the Sunday before the "Coming of Age day".

photo credits: toshimo1123 & nwhitely on flickr

Since 2009 we find the combination that still exists today, where the event is held on the fourth Saturday in January with a fireworks display of hundreds of fireworks.

On this matter, this is the only event in Nara that uses the Shakudama fireworks that have a diameter of over 30cm. An absolutely magical fireworks display that we guarantee will always remain engraved in your memories.

Mount Wakakusa

Mount Wakakusa is 342 meters high and 33 hectares wide and is covered with grass with delicate slopes. Here you can see deers, seasonal flowers and plants, like the traditional Japanese cherry trees in spring and the fantastic autumn colors typical of Japan. Also from its top, it is possible to see the whole panorama of the city of Nara with all its historical part.

photo credits: 158175735@N03 & mashipooh on flickr

Mount Wakakusa is surrounded by many UNESCO world heritage sites such as the temples Todaiji and Kohfukuji and the spring forest of Mount Kasuga, so be very careful to avoid accidents such as spreading the fire.

The parade

Led by the sound of shell horns played by the mountain priests of the Kinpusenji Temple, more than 40 people face the solemn parade through the park, wearing the traditional costumes of the representatives of the temples of Kasugataisha, Todaiji and Kohfukuji and of the officers of the judiciary office of Nara in the Edo period.

photo credits: toshimo1123 & katiefujiapple on flickr

The event begins with the Gojinkahotaisai, the sacred fire acceptance ceremony held at the Tobohino park, on the site of the Great Round Bonfire. In this ceremony, the sacred fire is transferred from the Great Round Bonfire to the torches. Following this, the parade will take the sacred fire to the Nogami temple. Once arrived at the Mizuya temple, the sacred fire brought by time Kasugataisha will be transferred to a series of torches. Once at the Nogami Temple, at the base of Mount Wakakusa, the sacred fire forms another great bonfire.

photo credits: katiefujiapple on flickr

During the parade, the fire is accompanied by constant prayers in the first place for the safety of the Yamayaki. The fire is then transferred back to the torches, accompanied by the songs of the priests of the temples Todaji, Kohfukuji and Kinpusenji. At this point, the parade moves towards the big bonfire in the center at the base of the mountain where it is lit, thus giving birth to the spectacle of light and heat.

photo credits: nara-park.com

Access

Mount Wakakusa is about a 10 - 15 minute walk from the Todaiji temple and Kasuga Taisha. The mountain can also be reached on foot from Kintetsu Nara station in about 35 minutes or from JR Nara station in about 50 minutes. Alternatively, you can use buses departing from both the station and Kasuga Taisha for a small fee.

If you are in Japan during this period, the next Yamamaki will take place in a few days, January 26, 2019. Do not miss it and we’ll wait for your stories!

photo credits: ks_photograph

Japan History: Hasekura Tsunenaga

photo credits: wikimedia.org

Tsunenaga Rokuemon Hasekura (1571 - 7 August 1622) was a Japanese samurai and servant of Date Masamune, the daimyo of Sendai, famous for having led numerous delegations of ambassadors that led him to travel the whole world.

He led a delegation of ambassadors in Mexico and later in Europe between 1613 and 1620, after which he returned to Japan. He was the first Japanese officer sent to America and the first to establish relations between France and Japan.

The Spaniards began their travels between Mexico ("New Spain") and China, through their territorial base in the Philippines, following the journeys of Andrés de Urdaneta in the sixteenth century. Manila became their definitive base for the Asian region in 1571.

Contacts with Japan began due to the continuous shipwrecks on the Japanese coast, at which point the Spaniards began to hope to expand the Christian faith in Japan. The attempts to expand their influence in Japan met strong resistance from the Jesuits, who had begun the evangelization of the country in 1549, as well as the Portuguese and the Dutch who did not wish to see Spain trade with the Japanese.

In 1609 the Spanish galleon San Francisco shipwrecked on the Japanese coast at Chiba due to bad weather on its way from Manila to Acapulco. The sailors were rescued, and the captain of the ship, Rodrigo de Vivero y Aberrucia, met Tokugawa Ieyasu.

A treaty under which the Spaniards could build an industry in the east of Japan was signed on November 29 1609, so that Spanish ships would be allowed to visit Japan if necessary.

The embassy project

Luis Sotelo, a Franciscan friar who was proselytizing in the Tokyo area, persuaded the Shōgun to send him as ambassador to Nueva España (Mexico). In 1610 he sailed to Mexico with the Spanish and 22 Japanese sailors aboard the San Buena Ventura, a ship built by the Englishman William Adams for the Shogun. Once in New Spain, Luis Sotelo met the Viceroy Luis de Velasco, who agreed to send an ambassador to Japan, in the person of the famous explorer Sebastián Vizcaíno, with the mission to explore the "Gold and Silver Islands" that were thought to be east of the Japanese islands.

Vizcaíno arrived in Japan in 1611 and had many meetings with the Shogun and the feudal lords, but he was not very respectful of Japanese customs, and he found the Japanese to be against Catholic proselytism. Vizcaíno eventually set off in search of the "Silver Island", during which he encountered bad weather, which forced him to return to Japan with serious damage. The Shogun decided to build a galleon in Japan, in order to bring Vizcaíno back to New Spain.

Statue of Hasekura Tsunenaga in Coria del Río

photo credits: tradurreilgiappone.com

Date Masamune was head of the mission and Hasekura Tsunenaga was appointed one of his attendants. Date Maru was called by the Japanese to build the galleon and later he was joined by San Juan Bautista, called by the Spaniards. With the participation of technical experts from the Bakufu, 800 naval workers, 700 blacksmiths, and 3,000 carpenters it took 45 days to build the whole ship.

After its completion, the ship sailed on 28 October 1613 from Ishinomaki to Acapulco in Mexico, with about 180 crew members, including 10 Shogun samurai, 12 samurai from Sendai, 120 between merchants, sailors and Japanese servants.

The ship arrived in Acapulco on 25 January 1614 after three months of navigation, and a ceremony welcomed the delegation. Before the trip to Europe, the delegation spent time in Mexico, visiting Veracruz and then embarking on the fleet of Don Antonio Oquendo. The emissaries left for Europe on the San Jose on 10 June, and Hasekura had to leave most of the group of Asian merchants and sailors in Acapulco.

The fleet arrived in Sanlúcar de Barrameda on October 5, 1614.

The Japanese embassy met the Spanish king Philip III in Madrid on January 30, 1615. Hasekura handed over a letter from Date Masamune to the sovereign and the offer for a treaty. The king replied that he would do what was in his power to meet the demands.

On February 17, Hasekura was baptized by the king's personal chaplain and renamed Felipe Francisco Hasekura.

Statue of Hasekura Tsunenaga in Civitavecchia

photo credits: tradurreilgiappone.com

France

After travelling through Spain, the delegation sailed into the Mediterranean Sea aboard three Spanish frigates to Italy. Because of the bad weather, the ships was forced to stay in the French bay of Saint Tropez, where they were received by the local nobility, with amazement from the population.

The visit of the Japanese people is recorded in the chronicles of the area as a delegation led by "Filippo Francesco Faxicura, Ambassador to the Pope, from Date Masamune, King of Woxu in Japan".

Many picturesque details of their behaviour and appearance were remembered:

"They never touch the food with their hands, but they use two thin sticks holding three fingers".

"They blow their noses in soft silky sheets of the size of a hand, which they never use twice, and then throw them on the ground after use, and were delighted to see that the people around them rushed to pick them up."

"Their swords cut so well that they can cut a thin sheet of paper by resting it on the edge and blowing on it."

("Reports of Mme de St Tropez", October 1615, Bibliothèque Inguimbertine, Carpentras).

The visit of Hasekura Tsunenaga to Saint Tropez in 1615 is the first documented example of relations between France and Japan.

Italy

The Japanese delegation arrived in Italy, succeeding in obtaining an audience with Pope Paul V in Rome, in November 1615, disembarking in the port of Civitavecchia, reason why even today Civitavecchia is twinned with the Japanese city of Ishinomaki. Hasekura handed the Pope a letter decorated with gold, with a formal request for a commercial treaty between Japan and Mexico, as well as sending Christian missionaries to Japan. The Pope accepted without delay to dispatch the sending of missionaries but left the decision of a commercial treaty to the King of Spain. The Pope then wrote a letter to Date Masamune, of which a copy is still preserved in the Vatican. The Senate of Rome gave Hasekura the honorary title of Roman Citizen, in a document which he later brought to Japan and which is still visible today and preserved in Sendai. In 1616, the French publisher Abraham Savgrain published an account of Hasekura's visit to Rome: "Récit de l'entrée solemnelle et remarquable faite à Rome, par Dom Philippe Francois Faxicura" ("Tale of the solemn and remarkable entry made in Rome by Don Filippo Francesco Faxicura ").

Conferral of honorary Roman citizenship to "Hasekura Rokuemon"

photo credits: wikimedia.org

Second visit to Spain

For the second time in Spain, Hasekura met the king, who declined the offer of a commercial treaty, because he thought that the Japanese people did not seem an official delegation of the sovereign of Japan, Tokugawa Ieyasu. He, on the contrary, had promulgated an edict in January 1614 ordering the expulsion of all the missionaries from Japan and had begun the persecution of the Christian faith in the country. The delegation left Seville for Mexico in June 1616 after a two-year period in Europe. Some of the Japanese remained in Spain, more precisely in a village near Seville (Coria del Río), and their descendants still have the surname Japón.

Return to Japan

In April 1618 the San Juan Bautista arrived in the Philippines from Mexico, with Hasekura and Luis Sotelo on board. The ship was bought by the Spanish government, with the aim of building defences against the Dutch. Hasekura returned to Japan in August 1620 and found the nation very changed: the persecution of Christians in the effort to eradicate Christianity had been active since 1614, and Japan was moving towards the "Sakoku" period, characterized by overwhelming isolationism. Because of these persecutions, the trade agreements with Mexico that he had tried to establish were denied, and much of the effort in this direction had been in vain.

It seems that the embassy he represented has had few results, but has instead accelerated Shogun Tokugawa Hidetada's decision to cancel trade relations with Spain in 1623 and diplomatic relations in 1624.

What happened to Hasekura after the diplomatic adventure is unknown, and the stories about his last years are numerous. Some argue that he abandoned Christianity, others said he defended his faith so deeply as to become a martyr, and others said he remained a Christian in intimacy, professing his faith in secret. Hasekura died in 1622, and his tomb is still visible today in the Buddhist temple of Enfukuji in the prefecture of Miyagi.

In 2015, was the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Keichō Kenō Shisetsudan, the first official delegation from Japan. A procession was held in historical costume in the main street of Civitavecchia for a historical re-enactment of the entrance to the city of the delegation led by a Hasekura Tsunenaga. In the evening, a concert was organized by local choral musicians at the Church of the Holy Japanese Martyrs. This event was also attended by Civitavecchia Mayor Antonio Cozzolino, Deputy Director of the Bureau of Reconstruction Policies of the city of Ishinomaki, Junichi Kondō, the Ambassador of Japan Kazuyoshi Umemoto and Consorte and citizens of both cities.

The delegation of Japan landing in Italy

photo credits: it.emb-japan.go.jp

Japan Travel: Meiji Shrine

The Meiji Era

The Meiji Period (明治 時代 Meiji jidai, "period of the illuminated kingdom") is one of Japan's most famous historical moments. It expands from October 23, 1868 until July 30, 1912 and includes the 44-year reign of Emperor Matsuhito.

photo credit: Wikipedia

Following the fall of the Tokugawa Yoshinobu shōgunate, the era of Emperor Meiji, the first with political power, began. It is precisely during these years that the political, social and economic structure of Japan began to change based on the Western model.

Following the death of Tokugawa Ieyasu in 1866, Tokugawa Yoshinobu was named as his successor, remaining in power a few months, until November 1867, when the shōgun submitted his resignation and ceded his powers to the court. In January 1868, Tokugawa's troops were replaced in Kyoto by a coup. And it is precisely in this period that the Meiji Restoration begins, restoring power to the emperor after centuries of shogun’s rule.

photo credit: Wikipedia

The first action exercised by the new Meiji government was to give some more privileges to the samurai class, which remained dissatisfied with the previous regime. Following the numerous contrasts in 1869 the daimyō were appointed governors of their feuds. However, the latter were suppressed in 1871, allowing the "formal" centralization of power and the reinforcement of the imperial institution. Not everyone agreed to the renunciation of their feuds, but to maintain order and stability, the government persuaded the daimyō with promises of strong rewards.

Along with this compromise, the government also compromised with the samurai class, approving a law that allowed them to carry out any occupation in the business field and public administration (the most popular were the institutional police body and the imperial army) . As a result of this, the maintenance of the samurai class was taken over by the central government, also by giving the remuneration.

In this new state, the image of the emperor became more and more significant and in June 1869, with the "oath of the Charter" in favor of the emperor Meiji, the first constitution was born. Here the full powers of the central government were enunciated, even if the political decisions of the country were still entrusted to an oligarchic government.

Until 1881, the regime governed in an authoritarian way with no opposition from the ruling class, but it is in this year that a great crisis broke out. Here, with a request to the emperor, he invoked the desire to transform the government into a parliamentary form.

photo credit: Wikipedia

Despite the difficulties, the Meiji period remains one of the most important eras and one with more changes in Japanese history. It is here that the foundations were laid for today's government of the Land of the Rising Sun.

The Meiji temple

Located in the heart of Tokyo and surrounded by a natural and urban forest, the Meiji-Jingu is a pearl of Shintōism and one of the city's most symbolic sanctuaries.

Located in the Yoyogi park, in Shibuya, the structure was completed in 1920, in honor of Emperor Meiji (1852 - 1912) and his wife Shôen (1849 - 1914). The shrine was also the victim of the bombings during the Second World War, but rebuilt completely soon after. This is a great demonstration of Japanese gratitude to this emperor, and the most striking example is the huge park that surrounds this place of worship, with more than one hundred thousand trees sent by the inhabitants of the archipelago in honor of the memory of this emperor.

To access the sanctuary, still in activity, you have to cross the large surrounding forest and pass under the magnificent Torii in cypress. Before you can enter the courtyards and sacred buildings, you must respect some rules of etiquette, such as the purification of the body with water and the greeting to the Torii.

It's amazing how after passing the big Torii gate, Tokyo's noisy comings and goings are replaced by the quiet sounds of the forest and the thick foliage of trees. Here temple visitors can take part in typical shinto activities, such as offerings in the main area, buying goodies and amulets, or writing your own wishes on the famous ema tablets. It is not rare, in fact, to find people of all ages who buy these wooden tablets and express their desire by writing on these supports. Once you have expressed your wish, you can hang the ema on a central support in the temple and subsequently they will be recovered by the priests who will then send messages to the Kami (gods).

The Meiji Jingu is one of the most popular temples in Japan and at this time of year, just after the Omisoka, it regularly welcomes more than three million visitors for the Hatsumode, the first prayers of the year.

In the northernmost part of the temple-related lands, visitors can find the treasure house of the Meiji Jingu, built a year after the temple was opened. In this place are contained many personal objects related to the Emperor and the Empress, including the carriage that accompanied the emperor to the formal declaration of the Meiji constitution in 1889.

A large area of the southern part of the temple lands is occupied by the Interior Gardens, which require a small entry fee. These gardens are particularly popular in mid-June to admire the blooming of the Iris flowers in all their glory, together with the famous Japanese gruidae birds. And if you have enough patience, you might have the opportunity to see a small flock of these fantastic birds cross the lake, a unique and magical spectacle.

Also, walking along the inner streets of the temple and the park, you can come across what I call "wall of sake", a wall of gigantic sake barrels, a gift for the emperor by all the sakagura of Japan . Opposite this wall, on the other hand, it is possible to find a wall of wine barrels, a gift to the emperor from all the foreign nations.

Also, in preparation for the 100th anniversary in 2020, renovations are taking place for some of the temple buildings, scheduled until October 2019, so if you plan to visit Tokyo in 2020 you can not miss this goal, between an Olympic race and the other!

Japan History: Tokugawa Ieyasu

Photo credits: wikipedia.org

Photo credits: wikipedia.org

Tokugawa Ieyasu (徳川家康, Jan. 30, 1543 - June 1, 1616) was the founder and first shōgun of the Tokugawa shogunate, who effectively commanded the Battle of Sekigahara in Japan in the 1600s until the reconstruction of Meiji in 1868. Ieyasu obtained power in 1600, became shōgun in 1603, and abdicated in 1605 remaining in power until his death in 1616. He was one of the three unifiers of Japan, along with Lord Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

Tokugawa Ieyasu, originally Matsudaira Takechiyo, was the son of Maytsudaira Hirotada, the daimyo of Mikawa of the Matsudaira clan and of Odai-no-kata, the daughter of the samurai lord Mizuno Tadamasa. His parents were 17 and 15 years old when Ieyasu was born.

In the year of his birth, the Matsudaira clan broke up. In 1543, Hirotada's uncle, Matsudaira Nobutaka, defeated the can Oda. This gave Oda Nobuhide a way to attack Okazaki. Hirotada divorced from Odai-no-kata by sending her back to his family to remarry again, in fact Ieyasu had 11 brothers and sisters.

As Oda Nobunaga continued to attack Okazaki, Hirotada in 1548 asked for help from Imagawa Yoshimoto who accepted the alliance.

Oda Nobuhide, having learned of this agreement, had Ieyasu kidnapped by his entourage on his way to Sunpu. Ieyasu was only five years old at the time.

Nobuhide threatened to execute Ieyasu unless his father broke all ties with the Imagawa clan. However, Hirotada refused, stating that sacrificing his son would show his seriousness in his pact with Imagawa. Despite this refusal, Nobuhide chose not to kill Ieyasu, but instead held him hostage for the next three years in the Manshoji Temple of Nagoya.

In 1549, when Ieyasu was 6 years old, his father Hirotada was assassinated by his own vassals, who had been corrupted by the Oda clan. Around the same time, Oda Nobuhide died during an epidemic. The death of Nobuhide has dealt a blow to the Oda clan. An army under the command of Imagawa Sessai besieged the castle where Oda Nobuhiro, the eldest son of Nobuhide and the new head of the Oda clan lived. With the castle about to fall, Sessai offered an agreement to Oda Nobunaga, the second son of Nobuhide. He offered to renounce the siege if Ieyasu had been delivered to Imagawa.

Photo credits: Rekishinotabi on flickr

The ascent to power (1556-1584)

In 1556 Ieyasu officially became an adult, with Imagawa Yoshimoto presiding over his genpuku ceremony. Following the tradition, he changed his name from Matsudaira Takechiyo to Matsudaira Jirōsaburō Motonobu. He was also allowed for a brief period to visit Okazaki to pay homage to his father's grave and to receive the homage of his nominal servants, guided by the karō Torii Tadayoshi.

A year later, he married his first wife, Lady Tsukiyama, a relative of Imagawa Yoshimoto, and changed his name to Matsudaira Kurandonosuke Motoyasu again. When he was allowed to return to Mikawa, Imagawa then ordered him to fight the Oda clan in a series of battles.

Motoyasu fought his first battle in 1558 at the Siege of Terabe. Terabe's castellan in western Mikawa, Suzuki Shigeteru, betrayed Imagawa by defeating Oda Nobunaga. This was within the territory of Matsudaira, so Imagawa Yoshimoto entrusted the campaign to Ieyasu and his servants of Okazaki. Ieyasu led the attack in person, but after taking external defenses, he began to be afraid of a counterattack, so he retired. As anticipated, the Oda forces attacked its lines, but Motoyasu was prepared and drove out the Oda army.

He managed to deliver supplies to the siege of Odaka in 1559. Odaka was the only one of the five frontier forts challenged by the Oda clan attack, nevertheless it remained in the hands of Imagawa. Motoyasu launched diversions against the two strong neighbors, and when the garrisons of the other forts came to his aid, Ieyasu's supply column managed to reach Odaka.

In 1560 the leadership of the Oda clan had passed to the brilliant leader Oda Nobunaga. Imagawa Yoshimoto, head of a large army (perhaps 25,000 people) invaded the territory of the Oda clan and Motoyasu was assigned a separate mission to capture the stronghold of Marune. So he and his men were not present at the Battle of Okehazama where Yoshimoto was killed in Nobunaga's surprise assault.

The Alliance with Oda

With the death of Yoshimoto and the Imagawa clan in a state of confusion, Motoyasu took the opportunity to assert his independence and bring his men back to the abandoned Okazaki castle to claim his place.

Motoyasu then decided to ally with the Oda clan. A secret agreement was needed because Motoyasu's wife, Lady Tsukiyama, and her newborn son, Nobuyasu, were held hostage to Sumpu by Imagawa Ujizane, Yoshimoto's heir.

In 1561, Motoyasu conquered the fortress of Kaminogō, detained by Udono Nagamochi, attacking in the night, setting fire to the castle and capturing two of the sons of Udono, who he used as hostages to free his wife and son.

In 1563 Nobuyasu was married to Nobunaga's daughter Tokuhime.

For the following years, Motoyasu undertook to reform the Matsudaira clan and make peace with Mikawa. He also strengthened his main vassals by assigning them lands and castles. These vassals included: Honda Tadakatsu, Ishikawa Kazumasa, Kōriki Kiyonaga, Hattori Hanzō, Sakai Tadatsugu and Sakakibara Yasumasa.

In the early days of Mikawa Ieyasu's daimyō he had difficult relationships with the temples of Jōdō, which became increasingly numerous in 1563-64.

During this period, the Matsudaira clan also faced a threat from a different source. Mikawa was an important center for the Ikkō-ikki movement, where the peasants united with the militant monks under the Jōdo Shinshū sect and rejected the traditional feudal social order. Motoyasu undertook several battles to suppress this movement in its territories, including the Battle of Azukizaka. In a fight, he was almost killed by two bullets that did not penetrate his armor. Both sides were using the new gunpowder weapons that the Portuguese introduced to Japan only 20 years earlier.

Photo credits: wikipedia.org

Photo credits: wikipedia.org

Growing political influence

In 1567, he changed his name again, this time to Tokugawa Ieyasu. In doing so, he claimed the descent from the Minamoto clan. No evidence was actually found for this alleged lineage from the Emperor Seiwa. Yet, his family name was changed with the permission of the Imperial Court, after writing a petition, in which he was awarded the courtesy title Mikawa-no-kami.

Ieyasu remained an ally of Nobunaga and his soldiers were part of the Nobunaga army that conquered Kyoto in 1568. At the same time Ieyasu was expanding its territory. Ieyasu and Takeda Shingen, the head of the Takeda clan in the province of Kai, made an alliance with the aim of conquering the whole territory of Imagawa. In 1570, Ieyasu's troops conquered the castle of Yoshida (modern Toyohashi), and entered the province of Tōtōmi. Meanwhile, the Shingen troops conquered the province of Suruga (including the capital of Imagawa, Sunpu). Imagawa Ujizane fled to the castle of Kakegawa, which Ieyasu laid siege to. Ieyasu then negotiated with Ujizane, promising that if he surrendered, he would help Ujizane regain Suruga. THe latter had nothing left to lose, and Ieyasu immediately ended his alliance with Takeda, forcing a new alliance with Takeda's enemy, Uesugi Kenshin of the Uesugi clan. Through these political manipulations, Ieyasu obtained support from the samurai of the Tōtōmi province.

In 1570, Ieyasu established Hamamatsu as the capital of his territory, placing his son Nobuyasu at the head of Okazaki.

The same year, he led 5,000 of his men to support Nobunaga at the Battle of Anegawa against the Azai and Asakura clans.

Conflict with Takeda

In October 1571, Takeda Shingen, now an ally of the Odawara Hōjō clan, attacked the Tokugawa lands at Tōtōmi. Ieyasu asked Nobunaga for help, receiving from him about 3,000 soldiers. At the beginning of 1572 the two armies met in the battle of Mikatagahara. The considerably larger Takeda army, under the expert leadership of Shingen, overwhelmed the Ieyasu’s troops and caused serious casualties. Despite his initial reticence, Ieyasu was persuaded by one of his generals to withdraw. The battle was a great defeat, but in the interest of maintaining the appearance of a dignified retreat, Ieyasu shamelessly ordered the men of his castle to light torches, play drums and leave the gates open, to adequately receive the returning warriors. To the surprise and relief of the Tokugawa army, this spectacle made General Takeda suspicious, so instead of besieging the castle, they camped out for the night. This error would have allowed a band of Tokugawa ninja to raid the field in the following hours, further disrupting Takeda's disoriented army, and in the end, Shingen's decision resulted in the cancellation of the entire offensive. Incidentally, Takeda Shingen would not have had another chance to advance on Hamamatsu, much less on Kyoto, since he would have died shortly after the siege of Noda Castle a year later, in 1573.

In 1575, Takeda attacked Nagashino Castle in the province of Mikawa. Ieyasu appealed to Nobunaga for help and the result was that Nobunaga personally headed a very large army (about 30,000 fighters). The Oda-Tokugawa force of 38,000 fighters won a great victory on June 28, 1575, at the Battle of Nagashino, however Takeda Katsuyori survived the battle and retreated back to the province of Kai.

For the next seven years, Ieyasu and Katsuyori fought a series of small battles, following which Ieyasu's troops managed to wrest control of the Suruga province from the Takeda clan.

In 1579, Ieyasu's wife and his heir Nobuyasu were accused by Nobunaga of conspiring with Takeda Katsuyori to assassinate Nobunaga, whose daughter Tokuhime (1559-1636) was married to Nobuyasu. This is why Ieyasu ordered his wife to be executed and forced his eldest son, Nobuyasu, to commit seppuku. Ieyasu then named his third son, Tokugawa Hidetada, as heir, since his second son was adopted by another rising power: the general of the Oda clan, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who would soon become the most powerful daimyo of Japan.

The end of the war with Takeda came in 1582 when a combined Oda-Tokugawa force attacked and conquered the province of Kai. Takeda Katsuyori was defeated at the Battle of Tenmokuzan and then committed seppuku.

Uma containing the ashes of Tokugawa Ieyasu in Nikkō

Uma containing the ashes of Tokugawa Ieyasu in Nikkō

Photo credits: wikipedia.org

Death of Nobunaga

At the end of June 1582, Ieyasu was near Osaka and far from his territory when he learned that Nobunaga had been murdered by Akechi Mitsuhide. Ieyasu managed the dangerous journey back to Mikawa and he was mobilizing his army when he learned that Hideyoshi had defeated Akechi Mitsuhide in the battle of Yamazaki.

Nobunaga's death meant that some provinces, governed by Nobunaga's vassals, could be conquered. The head of the province of Kai made the mistake of killing one of Ieyasu's helpers so he promptly invaded Kai and took control. Hōjō Ujimasa, head of the Hōjō clan, responded by sending his much larger army to Shinano and then to the province of Kai. No battle was fought between the Ieyasu’s troops and the great army of Hōjō. However, after some negotiations, Ieyasu and Hōjō accepted an agreement that left Ieyasu in control of the provinces of Kai and Shinano, while Hōjō took control of the province of Kazusa (as well as pieces from both the provinces of Kai and Shinano).

At the same time (1583) a war was waged to rule Japan between Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Shibata Katsuie. Ieyasu took no position in this conflict, relying on his reputation both for prudence and for wisdom. Hideyoshi defeated Katsuie at the Battle of Shizugatake and with this victory, he became the most powerful daimyo in Japan.

Ieyasu and Hideyoshi (1584-1598)

In 1584 Ieyasu decided to support Oda Nobukatsu, the eldest son and heir of Oda Nobunaga, against Hideyoshi. This was a dangerous act and could have led to the annihilation of the Tokugawa clan.

The Tokugawa troops took the traditional Oda stronghold of Owari while Hideyoshi replied by sending an army there. The Komaki campaign was the only time one of Japan's great unifiers fought each other. The campaign proved to be undecided, and after months of marches and unsuccessful feuds, Hideyoshi resolved the war through negotiation. First made peace with Oda Nobukatsu, and then offered a respite to Ieyasu. The agreement was stipulated at the end of the year and Ieyasu’s second son, Ogimaru (also known as Yuki Hideyasu) became Hideyoshi’s adoptive son.

Ieyasu's aide, Ishikawa Kazumasa, chose to join the daimyo and so he moved to Osaka to be with Hideyoshi. However, few other Tokugawa keepers have followed this example.

Hideyoshi was understandably suspicious of Ieyasu, and this was five years before they fought as allies. The Tokugawa did not participate in the invasions of Hideyoshi of Shikoku and Kyūshū.

In 1590, Hideyoshi attacked the last independent daimyo in Japan, Hōjō Ujimasa. The Hōjō clan ruled the eight provinces of the Kantō region in eastern Japan. Hideyoshi ordered them to submit to his authority, but they refused. Ieyasu, even if he was a friend and occasional ally of Ujimasa, joined his great strength of 30,000 samurai with the huge Hideyoshi army of about 160,000 men. Hideyoshi attacked several castles on the edge of the Hōjō clan with most of his army besieging Odawara Castle. Hideyoshi's army captured Odawara after six months. During this siege, Hideyoshi offered a radical deal to Ieyasu. He offered to Ieyasu the eight provinces of Kantō that were about to take from Hōjō in exchange for the five provinces Ieyasu controlled at the time, including Ieyasu’s one, Mikawa. Ieyasu accepted this proposal. Prey to the overwhelming power of the Toyotomi army, the Hōjō accepted the defeat, the top leaders Hōjō killed themselves and Ieyasu entered the field taking control of their provinces, putting an end to the clan kingdom of over 100 years.

The Battle of Sekigahara (1598-1603)

Hideyoshi, after another three months of illness, died on September 18, 1598. He was nominally succeeded by his young son Hideyori but, at only five years, the real power was in the hands of the regents. In the next two years Ieyasu made alliances with various daimyōs, especially those who had no love for Hideyoshi. Fortunately for Ieyasu, the oldest and most respected, Toshiie Maeda, died just a year later. With Toshiie's death in 1599, Ieyasu led an army to Fushimi and conquered Osaka Castle, Hideyori's residence. This angered the three remaining regents and began to structure their plans on all fronts for the war. It was also the last battle of one of Ieyasu's most loyal and powerful servants, Honda Tadakatsu.

The opposition to Ieyasu focused on Ishida Mitsunari, a powerful daimyo who was not one of the regents. Mitsunari conceived Ieyasu's death, and news about this plot reached some of the Ieyasu generals. They tried to kill Mitsunari but he escaped and obtained protection from none other than Ieyasu himself. It is not clear why Ieyasu protected a powerful enemy from his men, but he was a strategist and may have thought it would be better to drive the enemy army with Mitsunari rather than one of the regents.

Almost all Japanese daimyōs and samurai split into two factions: the western army (Mitsunari group) and the eastern army (anti-Mitsunari group). Ieyasu supported the anti-Mitsunari group and formed them as its potential allies. Ieyasu’s allies were the Date clan, the Mogami clan, the Satake clan and the Maeda clan. Mitsunari allied himself with the other three regents: Ukita Hideie, Mōri Terumoto and Uesugi Kagekatsu and many daimyō from the eastern end of Honshū.

In June 1600, Ieyasu and his allies transferred their armies to defeat the Uesugi clan, who was accused of planning an uprising against the Toyotomi administration. Before arriving in the territory of Uesugi, Ieyasu learned that Mitsunari and his allies had moved their army against Ieyasu. He held a meeting with the daimyos and they agreed to follow him, so he led most of his army west to Kyoto. At the end of the summer, Ishida's forces captured Fushimi.

Ieyasu and his allies marched along the Tōkaidō, while his son Hidetada followed the Nakasendō with 38,000 soldiers. A battle against Sanada Masayuki in Shinano province delayed Hidetada's forces, so they did not arrive in time for the main battle.

Fought near Sekigahara, this battle was the largest and one of the most important battles in Japanese feudal history. It began on October 211600, with a total of 160,000 men facing each other. The battle of Sekigahara ended with a complete victory of Tokugawa. The western block was crushed and in the following days Ishida Mitsunari and many other Western nobles were captured and killed and Tokugawa Ieyasu was now the de facto governor of Japan.

Immediately after the victory at Sekigahara, Ieyasu redistributed the land to the vassals who had served him, he left some the daimyōs unharmed, like the Shimazu clan, but others were completely destroyed. Toyotomi Hideyori (Hideyoshi's son) lost most of his territory that was under the management of the western daimyō, and was degraded to ordinary daimyō, not to a governor of Japan. In subsequent years the vassals who had sworn loyalty to Ieyasu before the battle became known as fudai daimyō, while those who promised him loyalty after the battle (in other words, after his power was unquestioned) were known as Tozama daimyō. The latter were considered inferior to the Fudai daimyōs.

Shōgun (1603-1605)

On March 24, 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu received the shōgun title from Emperor Go-Yōzei and he was 60 years old. He had survived all the other great men of his time: Nobunaga, Hideyoshi, Shingen, Kenshin. As shōgun, he used his last years to create and consolidate the Tokugawa shogunate, which inaugurated the Edo period and was the third shogunal government (after Kamakura), claiming the descent from the Minamoto clan, through the Nitta clan. His descendant will then marry into the Taira clan and the Fujiwara clan. The Tokugawa shogunate ruled Japan for the next 250 years.

Following a well-established Japanese model, Ieyasu abdicated his official shōgun position in 1605 and his successor was his son and heir, Tokugawa Hidetada. There may have been several factors that contributed to his decision, including his desire to avoid being bound by ceremonial duties, to make it harder for his enemies to attack the true center of power and to ensure a smoother succession of his son. The abdication of Ieyasu had no effect on the practical extension of his powers or his government. However, Hidetada assumed the formal role of the shogunal bureaucracy.

Ōgosho (1605-1616)

Ieyasu, as a retired shōgun (大 御所 ōgosho), remained the effective ruler of Japan until his death. He retired to Sunpu Castle, but also oversaw the construction of Edo Castle, an impressive construction project that lasted for the rest of Ieyasu's life. The result was the biggest castle in all of Japan, the cost of building it was supported by all the other daimyōs, while Ieyasu collected all the benefits. The central donjon, or tenshu, burned in 1657 and today, the Imperial Palace is in place of that castle.

In 1611 Ieyasu leading 50,000 men, visited Kyoto to witness the coronation of Emperor Go-Mizunoo. In Kyoto, Ieyasu ordered the reconstruction of the imperial court and buildings, forcing the remaining Western daimyos to sign an oath of loyalty to him.

In 1613, he composed the Kuge Shohatto (公家諸法度), a document that submitted the court under the daimyo’s close supervision, leaving them as simple ceremonial nominees.

In 1615 Ieyasu prepared the Buhat shohatto (武家諸法度), a document that illustrated the future of the Tokugawa regime.

Relations with foreign powers

Like Ōgosho, Ieyasu also oversaw diplomatic affairs with the Netherlands, Spain and England. Ieyasu chose to remove Japan from European influence from 1609, although the shogunate continued to grant preferential commercial rights to the Dutch East India Company and allowed them to maintain a "factory" for commercial purposes.

From 1605 until his death, Ieyasu frequently consulted with the English master of arms and pilot, William Adams, who, fluent in Japanese, assisted the shogunate in the negotiation of commercial relations.

Significant attempts to limit the influence of Christian missionaries in Japan date back to 1587 during Toyotomi Hideyoshi's shogunate. However, in 1614, Ieyasu was sufficiently concerned about the Spanish territorial ambitions that he signed an edict of Christian expulsion. The edict banished the practice of Christianity and led to the expulsion of all foreign missionaries. Although some minor commercial operations remained in Nagasaki, this edict drastically limited foreign trade and marked the end of Christian witness open in Japan until 1870.

Siege of Osaka

The last threat to Ieyasu's dominion was Toyotomi Hideyori, Hideyoshi’s son and rightful heir. He was now a young daimyo who lived in Osaka Castle. Many samurai who opposed Ieyasu gathered around Hideyori, claiming to be the legitimate ruler of Japan. Ieyasu criticized the opening ceremony of a temple built by Hideyori because it was as if he had prayed for the death of Ieyasu and the ruin of the Tokugawa clan. Ieyasu ordered Toyotomi to leave Osaka Castle, but the inhabitants refused and summoned the samurai to gather inside the castle. Then the Tokugawa, with a huge army led by Ieyasu and the shōgun Hidetada, besieged Osaka Castle in what is now known as the "winter siege of Osaka". In the end, Tokugawa was able to join the negotiations and an armistice after the attack and after threatening Hideyori's mother, Yodo-dono. However, once the treaty was agreed upon, Tokugawa filled the castle's outer moats with sand so that his troops could cross it. Through this stratagem, Tokugawa obtained a huge tract of land through negotiation and deception. Ieyasu returned to Sunpu Castle, but after Toyotomi refused another order to leave Osaka, he and his allied army of 155,000 soldiers attacked Osaka Castle again in the "Osaka Summer Siege".

Eventually, in 1615, Osaka Castle fell and almost all the defenders were killed including Hideyori, his mother (Hideyoshi's widow, Yodo-dono) and his newborn son. His wife, Senhime (Ieyasu’s niece), pleaded to save the lives of Hideyori and Yodo-dono, but Ieyasu refused and forced both to commit a ritual suicide, or perhaps both killed. In the end, Senhime was sent back to the Tokugawa clan alive.

The death

Ieyasu died at the age of 73 in 1616. It is thought that the cause of death was cancer or syphilis. The first Tokugawa shogun was posthumously deified with the name Tōshō Daigongen, the "Great Gongen, the light of the east". It is believed that a Gongen is a Buddha who appeared on Earth in the form of a kami to save sentient beings.

In life, Ieyasu had expressed th desire to be deified after his death to protect his descendants from evil. His remains were buried in the Gongen mausoleum in Kunōzan, Kunōzan Tōshō-gū. As a general opinion, many people believe that after the first anniversary of his death, his remains were buried again in the Nikkō Shrine, Nikkō Tōshō-gū and they are still there today. Neither of the two sanctuaries offered to open the tombs, so the location of the physical remains of Ieyasu is still a mystery. The architectural style of the mausoleum became known as gongen-zukuri, or gongen style. First he was given the Buddhist name Tosho Dai-Gongen, then after his death he was changed to Hogo Onkokuin.

Ieyasu Tomb in Tōshō-gū

Ieyasu Tomb in Tōshō-gū

Photo credits: wikipedia.org

Ieyasu's rule era

Ieyasu had a number of qualities that enabled him to rise to power. He was both attentive and audacious, in the right times and in the right places. Calculating and subtle, Ieyasu changed alliances when he thought he would benefit from the change. He allied himself with the late Hōjō clan, then he joined the army of conquest of Hideyoshi, who destroyed Hōjō and he himself took over their lands. In this he was like the other daimyo of his time. That was an era of violence, sudden death and betrayal. He was neither very popular nor personally popular, but he was feared and respected for his leadership and his cunning. For example, he wisely kept his soldiers out of Hideyoshi's campaign in Korea.

He was capable of great loyalty: once he allied himself with Oda Nobunaga, he never went against him, and both leaders took advantage of their long alliance. He was known to be loyal to his friends, and was said to have a close friendship with his vassal Hattori Hanzō. It is said, however, that he remembered the wrongs he had suffered and that he executed a man because he had insulted him when he was young.

Ieyasu protected many former Takeda servants from the wrath of Oda Nobunaga, who was known to harbor a bitter rancor toward Takeda. But he also knew he was ruthless, for example, he ordered the executions of his first wife and his eldest son, a son-in-law of Oda Nobunaga and he was also Hidetada's wife uncle.

He was cruel, implacable and ruthless in eliminating Toyotomi survivors after Osaka. For days, dozens and dozens of men and women were hunted down and executed, including Hideyori’s eight-year-old son from a beheaded concubine.

Unlike Hideyoshi, he had no desire to win anything outside of Japan. He just wanted to bring order, end the open war and rule Japan.

While at the beginning it was tolerant of Christianity, its attitude changed after 1613 and Christian executions increased sharply.

Ieyasu's favorite pastime was falconry. He considered it an excellent training for a warrior. "When you go to the countryside, you learn to understand the military spirit and the hard life of the lower classes: you exercise your muscles and you train your limbs. You can walk and run and become indifferent to the heat and cold, and therefore it is very unlikely that you may suffer from some disease ". Ieyasu often swam and even in old age it is said that he swam in the moat of Edo Castle.

He also took a scholarship and religion, attending scholars such as Hayashi Razan.

Two of his famous quotes

Life is like a long journey with a heavy burden. Let your pace be slow and steady, do not stumble. Persuade yourself that imperfection and inconvenience are the greatest thing of mortals, and there will be no room for dissatisfaction or despair. When ambitious wishes arise in your heart, remember the days of extremism that you went through. Tolerance is the root of all tranquility and security forever. Watch the wrath of your enemy. If you only know what it means to conquer, and you do not know what it means to defeat. Find flaws in yourself rather than others.

The strong virile in life are those who understand the meaning of the word patience. Patience means limiting one's inclinations. There are seven emotions: joy, anger, anxiety, adoration, pain, fear and hate, and if a man does not give way to these he can be called a patient. I'm not as strong as I could be, but I always knew and practiced patience. And if my descendants want to be as they are, they have to study patience.