Japan History: Italy & Japan 150 Years of Friendship

Italy & Japan 150 Years of Friendship

Photo Credits: Ambasciata del Giappone

150 years of friendship between Italy and Japan was celebrated in 2016.

This relationship between these two countries dates back to 1866, on the 4th of July, when an Italian military ship sent by King Vittorio Emanuele II arrived in Yokohama port to offering a treaty of friendship and commerce.

Back then, both countries had a common goal. They were eager to close the economic distance that separating them from the other more influential and powerful countries in those days.

Photo Credits: L'inviato Speciale

An alliance for better or for worse

After the end of First World War, Italy and Japan experienced same outcome. They both won the conflict, however both felt "betrayed" following the Versailles Treaty. Italy suffered from the indignation of not getting all the territories that it expected while Japan suffered from diplomatic defeats in the rejection of Japan's bid for a racial equality. Moreover, the two countries were experiencing critical post-conflict economic situations that would have led towards a totalitarian regime of the Second World War.

In 1937, Italy went against the Russian’s communist politics, like how Japan did when they signed the Anti-Komintern Pact with Hitler's Germany. In the following year, the fascist national party landed in Japan, and Mussolini's works were translated into Japanese. The Germany-Japan-Italy Tripartite Agreement was signed, creating the Rome-Berlin-Tokyo alliance. In that period Mussolini made several visits to Japan.

All those who refused to join the fascist party in Japan were interned in the camps at Nagoya.

The atomic bombs dropped to Nagasaki and Hiroshima hit Japan hard and both Italy and Japan had to recover from the tragedies caused by the war. At the end of the Second World War, both countries underwent radical transformations.

Photo Credits: Il turista curioso.it

An eternal bridge

The bridges built between the two countries continued to multiply over the years. In 1970, the first intercontinental television link between NHK and RAI broadcasters led to new cultural exchanges, allowing the products and lifestyles, from food to martial arts and increasingly intense linguistic exchanges, to grow ever closer.

In recent times, the mutual influence between the two nations also translated into architectural works.

Architect Kenzo Tange, who gave Tokyo its present-day landscape, designed numerous buildings in Italy, like the towers of the Bologna exhibition center and the business center of Naples, while Renzo Piano designed the Osaka airport and Ushibuka Bridge.

These days, Japan and Italy continue to enjoy cordial and friendly exchanges, growing and strengthening their relationship with each other as they always have through the past 150 years.

Metropolitan Governement Building Shinjuku Park Tower

Photo Credits: Japan italy Bridge

Ushibuka bridge, Photo Credits: Wikipedia.org

Japan History: Forty-seven Ronin

FORTY-SEVEN RŌNIN

A band of rònin (samurai without leader) avenged the death of their master. The event is known as the revenge of the forty-seven rōnin (四 十七 士 Shi-jū-shichi-shi, forty-seven samurai), also as the Akō incident (Akō jiken) or Akō's revenge, and is considered an historical event in Japan.

Photo Credits: Wikipedia.org

The story tells of a group of samurai remaining without leader after their daimyō Asano Naganori was forced to execute seppuku for assaulting Kira Yoshinaka, a court official whose title was Kōzuke no suke. After waiting and planning for a year, the rōnin avenged their master's honor by killing Kira. In turn, they were forced to commit seppuku because of the murder crime. This story has been made popular in Japanese culture as a symbol of loyalty, sacrifice, perseverance and honor, values people should look for in their daily lives. The story's popularity grew during the Meiji era, when Japan underwent rapid modernization, and the legend became important in national heritage and identity.

The fictional stories of the Forty-seven Rönin are known as Chūshingura. The story has been made popular in numerous shows, including bunraku and kabuki. Because of the shogunate laws of censorship in the Genroku era, which prohibited the portrayal of current events, the names were changed. The first Chūshingura was written about 50 years after the event.

The censorship laws had subsided a bit 75 years later, at the end of the eighteenth century, when Isaac Titsingh recorded for the first time the history of the forty-seven rōnin as one of the significant events of the Genroku era. It continues to be popular in Japan, and every year on December 14, in the Sengakuji Temple, where Asano Naganori and the rōnin are buried, a festival is held to commemorate the event.

In 1701, two daimyōs, Asano Takumi-no-Kami Naganori and Lord Kamei Korechika of the Tsuwano domain, were ordered to organize a reception for the emperor's messengers to the castle of Edo, during their sankin-kōtai service to the shōgun .

Asano and Kamei were to receive instructions on the necessary court code from Kira Kozuke-no-Suke Yoshinaka, a powerful Tokugawa Tsunayoshi shogunate official. He got very angry with them, either because of the insufficient gifts they offered him, or because they could not provide the bribe requests. Other sources describe him as naturally rude and arrogant or corrupt, this behavior offended Asano, a devoutly moral confucian. According to some reports, it seems that Asano was not familiar with the complexities of the shogunate court and had not shown the right amount of deference to Kira.

Initially, Asano endured everything stoically, while Kamei raged and prepared to kill Kira to avenge the insults. However, Kamei's advisors avoided the disaster for their lord and teamed up by collecting and giving Kira a big bribe; Kira then began to treat Kamei well and this contributed to calm him down.

However, Kira continued to treat Asano hard to the point of insulting him, calling him a country farmer without good manners, and Asano eventually stopped holding back. At Matsu no Ōrōka, the main hallway of Honmaru Goten residence, Asano lost his temper and attacked Kira with a dagger, wounding him in the face. They had to intrude the guards to separate them.

Kira's injury was not severe, however attacking a shogunate official within the boundaries of the shogun's residence was considered a serious crime. Any violence was completely forbidden in Edo's castle. Akō's daimyō had used his dagger inside Edo Castle, and for this crime, he was ordered to make seppuku. Asano's assets and lands had to confiscated after his death, his family had to be ruined, and his servants had to become rōnin,according to the general rule of the time.

The news arrived to Ōishi Kuranosuke Yoshio, Asano's chief adviser, who took over the command and transferred the Asano family before delivering the castle to government agents.

Forty-seven men, among the over 300, and especially their leader Ōishi, refused to allow their lord to take revenge. They teamed up in secret swearing to avenge their master and kill Kira, even though they knew they would be severely punished for that.

Kira was however well guarded and his residence had been protected. The ronin realized they should not rise Kira’s and other shogunate authorities suspicion, so they dispersed and became merchants and monks.

Ōishi took residence in Kyoto and began to frequent brothels and taverns. Kira feared a trap and sent spies to monitor the former servants of Asano.

One day, Ōishi, returning home drunk, fell down and fell asleep in the street. A man, Satsuma, was so enraged by this behavior of a samurai that he began to insult him, kicking him in the face and spitting on him.

Not long after, Ōishi divorced from his faithful wife after twenty years of marriage. He did not want to harm her her when the rōnin would have taken their revenge. He sent her away with their two younger children to live with her parents. He asked their eldest son, Chikara, whether he would have preferred to stay and fight or leave. Chikara stayed with his father.

Ōishi started to behave in a strange way and very different from the samurai style. He attended geishas (particularly Ichiriki Chaya), he drank every night and spoke obscenely in public. Ōishi's servants bought a geisha, hoping she would calm him down. All this was a plot to free Ōishi from Kira’s spies.

Kira's agents reported all this to Kira. Kira was then convinced he was safe from the servants of Asano, considering one year and a half elapsed he judged them without the courage to avenge their master. Thinking they were harmless, he lowered his guard.

The rest of the rōnin gathered in Edo, and in their roles as merchants and workers, had access to Kira's house, becoming familiar with the environment and people. Okano Kinemon Kanehide married the daughter of one of the builders of the house, managing to get the project. All this was reported to Ōishi. Others gathered and transported their weapons to Edo.

After two years, Ōishi was convinced that Kira was completely unaware, and everything was ready, He left Kyoto, avoiding the spies watching him, and joined the whole band gathered in a secret meeting place in Edo to renew their oaths.

On January 30, 1703 early in the morning, Ōishi and another rōnin attacked Kira Yoshinaka's home in Edo. According to a carefully defined plan, they would divide into two groups and would attack armed with swords and bows. A group, led by Ōishi, would attack the main gate; the other, led by his son, Ōishi Chikara, would attack the house through the back gate. A drum would sound the simultaneous attack, and a whistle would signal Kira's death.

Once dead, they planned to cut Kira's head and place it as an offering on their master's grave. They would then wait for their planned death sentence. All this had been agreed during a final dinner, during which Ōishi had asked to be careful and save women, children and other defenseless people.

Photo Credits: Wikipedia.org

Ōishi had four men at the fence and entered the caretaker's house, capturing and binding the guard. He then sent messengers to all neighboring houses, to explain that they were not robbers, but servants avenging the death of their master, and that no harm would be done to others: the neighbors were all safe. One of the rōnin climbed up to the roof and announced aloud to the neighbors that the matter was an act of revenge. The neighbors, who hated Kira, were relieved and did nothing to thwart the plan.

Dopo aver appostato gli arcieri per impedire agli abitanti di chiedere aiuto, Ōishi suonò il tamburo per iniziare l'attacco. Ten of the Kira keepers prevented the attack on the house from the front, but Chiishi Chikara's side is attacked from the back.

Following setting up of the archers to prevent house residents asking for help, Oishi played the drum to start the attack. Ten of the Kira keepers prevented the attack of the house from the front, allowing Chiishi Chikara to attack from the back.

Kira, terrified, took refuge in a closet on the veranda, along with his wife and his maids. The rest of his servants, sleeping in the barracks outside, tried to enter the house to save him. After passing the defenders at the front of the house, the two parts led by father and son joined and fought the servants who were entering. The latter, realizing they were about to lose, tried to ask for help, but their messengers were killed by the archers already set up to prevent this.

After a fierce fight, the last of Kira's servants was defeated; the ronin killed 16 men of Kira and wounded 22, including his nephew. However, no signs about Kira. They searched the house, they heard women and children cry. They were beginning to despair, when Ōishi checking Kira's bed, discovered that it was still warm, so he knew Kira could not be far away.

In a courtyard hidden in the back, they discovered a man who was hiding and was easily disarmed.

He refused to say who he was, the ronin however knew he was Kira and they whistled. The rōnin gathered and Ōishi, with a lantern, confirmed he was indeed Kira and as a final proof, he discovered on his head a scar of Asano's attack.

Ōishi knelt, and in consideration of Kira’s high degree, he respectfully addressed him, telling him that they were Asano's servants, come to avenge him as the true samurai should, and inviting him to die like a true samurai should , killing himself. Ōishi said he would act like a kaishakunin ("second", the one beheading a person who committed seppuku to spare him being unworthy of death) and offered him the same dagger that Asano used to kill himself.

However, no matter how much they begged him, Kira crouched, wordlessly trembling. Seeing that it was useless to continue, Ōishi ordered the other rōnin to killed him by cutting off his head with the dagger.

They turned off all the lamps and fires in the house and left with Kira's head.

One of the rōnin, Terasaka Kichiemon, was ordered to go to Akō and report that their revenge had been completed. (Although the role of Kichiemon as a messenger is the most accepted version of the story, other sources see him escape before or after the battle).

The rōnin, on their way back to Sengaku-ji, stopped in the street to rest and refresh themselves.

Photo Credits: Wikipedia.org

At dawn, they quickly brought Kira's head from his residence to the tomb of their lord in the temple of Sengaku-ji, marching for about ten kilometers across the city, causing a great sensation on the road. The story of revenge spread rapidly and everyone praised them and offered them refreshment during their journey.

Arrived at the temple, the remaining 46 rōnin (all except Terasaka Kichiemon) washed Kira's head in a well, and set it down with the dagger in front of Asano's tomb. They then offered prayers to the temple and gave the temple monk the remaining money, asking him to bury them decently and offer prayers for them. The group was divided into four parts and placed under the guard of four different daimyōs.

Two friends of Kira came to take his head for burial.

Edo shogunate’s officials were embarrassed. The samurai had followed the precepts by avenging their lord's death; however they also challenged the shogunate's authority by executing revenge, which was forbidden. As expected, the rōnin were sentenced to death for Kira's murder; the shogun eventually ordered them to commit honorably seppuku instead of having them executed as criminals. It is known that each of the assailants ended his life in a ritual manner. Ōishi Chikara, the youngest, was only 15 years old on the day of the attack, and only 16 the day he committed seppuku.

Each of the 46 rōnin killed himself on February 4, 1703. The forty-seventh ronin, identified as Terasaka Kichiemon, eventually returned from his mission and was forgiven by the shogun (it is said because of his youth). He lived until the age of 87, dying in 1747, and was buried with his companions. The assailants who died of seppuku were buried in the ground of Sengaku-ji, in front of the tomb of their master.

Their clothes and weapons are still kept in the temple, along with the drum and the whistle; their armor was all homemade, since they did not want to raise suspicion by buying one.

The tombs became a place of veneration and people gathered there in prayer. They were visited by many people over the years since the Genroku era. One of the visitors, Satsuma who laughed and spat at Ōishi in Kyoto, begged forgiveness for his actions and for thinking that Ōishi was not a true samurai. He then committed suicide and was buried near the river.

Although revenge was seen as an act of loyalty, there was actually a second goal: re-establishing Asano's lordship and finding a place where their fellow samurai could serve. Hundreds of samurai who served Asano had been left without work, and many were unable to find a job, as they had served under a dishonored family. Many lived as farmers or did simple crafts to make their living. The revenge of the forty-seven ronin erased their names and many of the unemployed samurai found work.

Photo Credits: Wikipedia.org

The Forty-seven Rōnin

Ōishi Kuranosuke Yoshio/Yoshitaka (大石 内蔵助 良雄)

Ōishi Chikara Yoshikane (大石 主税 良金)

Hara Sōemon Mototoki (原 惣右衛門 元辰)

Kataoka Gengoemon Takafusa (片岡 源五右衛門 高房)

Horibe Yahei Kanamaru/Akizane (堀部 弥兵衛 金丸)

Horibe Yasubei Taketsune (堀部 安兵衛 武庸)

Yoshida Chūzaemon Kanesuke (吉田 忠左衛門 兼亮)

Yoshida Sawaemon Kanesada (吉田 沢右衛門 兼貞)

Chikamatsu Kanroku Yukishige (近松 勘六 行重)

Mase Kyūdayū Masaaki (間瀬 久太夫 正明)

Mase Magokurō Masatoki (間瀬 孫九郎 正辰)

Akabane Genzō Shigekata (赤埴 源蔵 重賢)

Ushioda Matanojō Takanori (潮田 又之丞 高教)

Tominomori Sukeemon Masayori (富森 助右衛門 正因)

Fuwa Kazuemon Masatane (不破 数右衛門 正種)

Okano Kin'emon Kanehide (岡野 金右衛門 包秀)

Onodera Jūnai Hidekazu (小野寺 十内 秀和)

Onodera Kōemon Hidetomi (小野寺 幸右衛門 秀富)

Kimura Okaemon Sadayuki (木村 岡右衛門 貞行)

Okuda Magodayū Shigemori (奥田 孫太夫 重盛)

Okuda Sadaemon Yukitaka (奥田 貞右衛門 行高)

Hayami Tōzaemon Mitsutaka (早水 藤左衛門 満尭)

Yada Gorōemon Suketake (矢田 五郎右衛門 助武)

Ōishi Sezaemon Nobukiyo (大石 瀬左衛門 信清)

Isogai Jūrōzaemon Masahisa (礒貝 十郎左衛門 正久)

Hazama Kihei Mitsunobu (間 喜兵衛 光延)

Hazama Jūjirō Mitsuoki (間 十次郎 光興)

Hazama Shinrokurō Mitsukaze (間 新六郎 光風)

Nakamura Kansuke Masatoki (中村 勘助 正辰)

Senba Saburobei Mitsutada (千馬 三郎兵衛 光忠)

Sugaya Hannojō Masatoshi (菅谷 半之丞 政利)

Muramatsu Kihei Hidenao (村松 喜兵衛 秀直)

Muramatsu Sandayū Takanao (村松 三太夫 高直)

Kurahashi Densuke Takeyuki (倉橋 伝助 武幸)

Okajima Yasoemon Tsuneshige (岡島 八十右衛門 常樹)

Ōtaka Gengo Tadao/Tadatake (大高 源五 忠雄)

Yatō Emoshichi Norikane (矢頭 右衛門七 教兼)

Katsuta Shinzaemon Taketaka (勝田 新左衛門 武尭)

Takebayashi Tadashichi Takashige (武林 唯七 隆重)

Maebara Isuke Munefusa (前原 伊助 宗房)

Kaiga Yazaemon Tomonobu (貝賀 弥左衛門 友信)

Sugino Jūheiji Tsugifusa (杉野 十平次 次房)

Kanzaki Yogorō Noriyasu (神崎 与五郎 則休)

Mimura Jirōzaemon Kanetsune (三村 次郎左衛門 包常)

Yakokawa Kanbei Munetoshi (横川 勘平 宗利)

Kayano Wasuke Tsunenari (茅野 和助 常成)

Terasaka Kichiemon Nobuyuki (寺坂 吉右衛門 信行)

Japan History: Date Masamune

Date Masamune

Photo Credits: samurai-archives.com

Date Masamune (伊達 政宗, September 5, 1567 – June 27, 1636) was a regional ruler of Japan's Azuchi–Momoyama period (last part of the Sengoku period) through early Edo period. Heir to a long line of powerful daimyōs in the Tōhoku region, he went on to found the modern-day city of Sendai. An outstanding tactician, he was made all the more iconic for his missing eye, as Masamune was often called dokuganryū (独眼竜), or the "One-Eyed Dragon of Ōshu".

Early life

Date Masamune was born as Bontemaru (梵天丸) in Yonezawa Castle (in modern Yamagata Prefecture). He was the eldest son of Date Terumune, a lord of the Rikuzen area of Mutsu, and Yoshihime, a daughter of Mogami Yoshimori, daimyo of the Dewa province. He recieved the name Tojirou (藤次郎) Masamune in 1578, and the following year he married Megohime, the daughter of Tamura Kiyoaki, lord of Miharu castle, in Mutsu Province. At the age of 14, in 1581, Masamune led his first campaign, helping his father fight the Sōma family. In 1584, at the age of 17, Masamune succeeded his father, Terumune, who chose to retire from his position as daimyō.

Masamune's army was recognized by its black armor and golden headgear. Masamune himself is known for a few things that made him stand out from other daimyōs of the time. In particular, his famous crescent-moon-bearing helmet won him a fearsome reputation.

As a child, smallpox robbed him of sight in his right eye, though it is unclear exactly how he lost the organ entirely. Various theories behind the eye's condition exist. Some sources say he plucked out the eye himself when a senior member of the clan pointed out that an enemy could grab it in a fight. Others say that he had his trusted retainer Katakura Kojūrō gouge out the eye for him, and this, together with his fearsome temperament, made him the 'One-Eyed Dragon' of Ōshu.

Military campaign

The Date clan had built alliances with neighboring clans through marriages over previous generations, but local disputes remained commonplace. Shortly after Masamune's succession in 1584, a Date retainer named Ōuchi Sadatsuna defected to the Ashina clan of the Aizu region. Masamune declared war on Ōuchi and the Ashina for this betrayal, and started a campaign to hunt down Sadatsuna. Many clans, even formerly amicable allies, fell. In the winter of 1585, one of these allies, Hatakeyama Yoshitsugu, felt defeat was approaching and chose to surrender to the Date. Masamune agreed to accept the surrender, but on the heavy condition that the Hatakeyama give up most of their territory to the Date. This resulted in Yoshitsugu kidnapping Masamune's father, Terumune, during their meeting in Miyamori Castle, where Terumune was staying at during the time. The incident ended with the death of Terumune, while fleeing Hatakeyama men clashed with the Date troops near the Abukuma river.

A general war ensued between the Date and Hatakeyama, the latter drawing on support from the Satake, Ashina, Soma, and other local clans. The allies marched to within a half-mile of Masamune's Motomiya-jo, assembling some 30,000 troops for the attack. Masamune, having only 7,000 warriors, prepared a defensive strategy, relying on the series of forts that guarded the approaches to Motomiya. The fighting began on the 17th of November, and did not progress well for the Date. Three of his valuable forts were taken, and one of his chief retainers, Moniwa Yoshinao, was killed in a duel with an opposing commander. The attackers pressed towards the Seto River, which was the last obstacle between them and Motomiya. Date attempted to turn them back at the Hitadori Bridge, but was driven back. Masamune brought his remaining forces within Motomiya's walls, and prepared for what would surely be a gallant but futile last stand. But the next morning,the main enemy contingent picked up and marched away. These were Satake Yoshishige's men. Their lord had received word that in his absence the Satomi had attacked his lands in Hitachi. Apparently this left the allies with fewer men than they believed possible to bring down Motomiya, for they too retreated by the end of the day. This brush with utter defeat was likely a factor in turning Masamune into the renowned general he would one day be known as. In the wake of the battle, peace was struck with the Hatakeyama and Soma, although this was to prove short-lived.

In 1589, Date defeated the Soma, and bribed an important Ashina retainer, Inawashiro Morikuni, over to his side. He then assembled a powerful force and marched straight for the Ashina's headquarters at Kurokawa. The Date and Ashina forces met at Suriagehara on 5 June when Masamune's forces overcame the faltering Ashina ranks, breaking them. Unfortunately for the Ashina, Date men had destroyed their avenue of escape, a bridge over the Nitsubashi River, and those who did not drown attempting to swim to safety were mercilessly put to the sword.

By the battle's end, Masamune could count something like 2,300 enemy heads in one of the more bloody and decisive battles of the Sengoku period. Masamune then proceeded to make the rich Aizu domain his base of operations.

However, this would be Date Masamune's last expansionist adventure.

Photo credits: wattention.com

Statua di Date Masamune nella città di Sendai sulle rovine del Castello di Sendai,

Service under Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu

In 1590, Toyotomi Hideyoshi seized Odawara Castle and compelled the Tōhoku-region daimyōs to participate in the campaign. Although Masamune refused Hideyoshi's demands at first, he had no real choice in the matter since Hideyoshi was the virtual ruler of Japan. However, the delay infuriated Hideyoshi. Expecting to be executed, Masamune, wore his finest clothes showing no fear in facing his angry overlord. But Hideyoshi spared his life, saying that "He could be of some use".

Following the conclusion of the siege, Masamune was forced to relinquish his newly won holdings in Aizu and was give Iwatesawa and the surrounding lands. Lands that would have earned him less, though. Masamune moved there in 1591, rebuilt the castle renaming it Iwadeyama, and encouraged the growth of a town at its base. Masamune stayed at Iwadeyama for 13 years and turned the region into a major political and economic center.

He and his men served with distinction in the Korean invasions under Hideyoshi and, after Hideyoshi's death, he began to support Tokugawa Ieyasu, apparently at the advice of Katakura Kojūrō. For this reason Masamune was awarded with the lordship of the huge and profitable Sendai Domain, which made Masamune one of Japan's most powerful daimyōs. Tokugawa had promised Masamune a one-million koku domain but, even after substantial improvements were made, the land only produced 640,000 koku. And most of the earnings were used to feed the Edo region. In 1604, Masamune, accompanied by 52,000 vassals and their families, moved to what was then the small fishing village of Sendai. He left his fourth son, Date Muneyasu, to rule Iwadeyama.

Masamune would turn Sendai into a large and prosperous city.

Although Masamune was a patron of the arts and sympathized with foreign causes, he was also an aggressive and ambitious daimyō. When he first took over the Date clan, he suffered a few major defeats from powerful and influential clans such as the Ashina. These defeats were arguably caused by recklessness on Masamune's part.

Being a major power in northern Japan, Masamune was naturally viewed with suspicion. Toyotomi Hideyoshi had reduced the size of his land after his tardiness in coming to the Siege of Odawara against Hōjō Ujimasa. Later, Tokugawa Ieyasu increased the size of his lands again, but was constantly suspicious of Masamune and his policies.

Although Tokugawa Ieyasu and other Date allies were always suspicious of him, Date Masamune for the most part served both Toyotomi and Tokugawa loyally. He took part in Hideyoshi's campaigns in Korea, and in the Osaka campaigns too. When Tokugawa Ieyasu was on his deathbed, Masamune visited him and read him a piece of Zen poetry.

Masamune was highly respected for his ethics, and a still-quoted aphorism is, "Rectitude carried to excess hardens into stiffness; benevolence indulged beyond measure sinks into weakness."

Patron of culture and Christianity

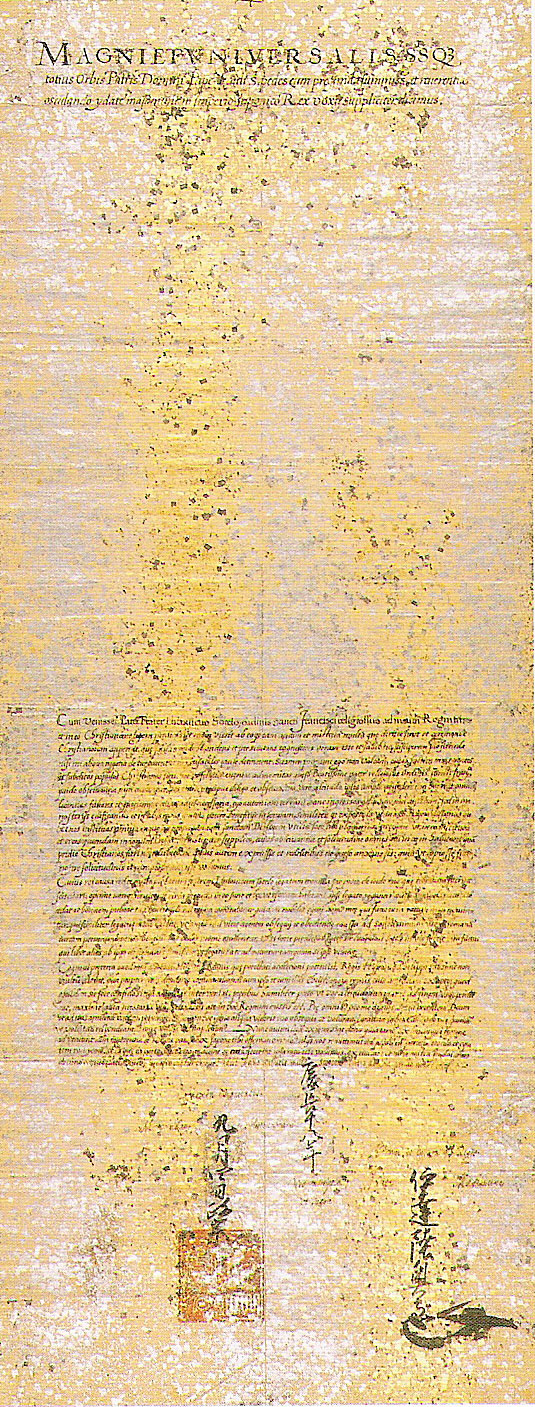

Photo Credits: wikimedia.org

Una lettera scritta da Masamune al Papa Paolo V

Masamune expanded trade in the otherwise remote, backwater Tōhoku region. Although initially faced with attacks by hostile clans, he managed to overcome them after a few defeats. In the end, he eventually ruled one of the largest fiefdoms of the later Tokugawa shogunate. He built many palaces and worked on many projects to beautify the region. For 270 years, Tōhoku remained a place of tourism, trade and prosperity. Matsushima, for instance, a series of tiny islands, was praised for its beauty and serenity by the wandering haiku poet Matsuo Bashō.

Other than being known to have encourage foreigners to come to his land, Masamune also showed sympathy for Christian missionaries and traders in Japan. In addition to allowing them to come and preach in his province, he also released the prisoner and missionary Padre Sotelo from the hands of Tokugawa Ieyasu. Date Masamune allowed Sotelo as well as other missionaries to practice their religion and win converts in Tōhoku.

Moreover, he funded and promoted an expedition to establish diplomatic relations with the Pope in Rome, even though he was likely motivated at least in part by a desire for foreign technology. In this, he was similar to other lords, such as Oda Nobunaga. For the expedition he ordered the building of the exploration ship Date Maru or San Juan Bautista, using European ship-building techniques. He sent one of his retainers, Hasekura Tsunenaga, Sotelo, and an embassy numbering 180 people on a successful voyage that included places as the Philippines, Mexico, Spain and Rome, of course. Previously, Japanese lords had never funded this sort of venture, so it was probably the first of such voyages. At least five members of the expedition stayed in Coria, Spain, to avoid the persecution of Christians in Japan. 600 of their descendants, with the surname Japón (Japan), are now living in Spain.

When the Tokugawa government banned Christianity, Masamune had to obey the law reversing his position, and though disliking it, let Ieyasu persecute Christians in his domain. However, some sources suggest that Masamune's eldest daughter, Irohahime, was a Christian.

Photo credits: it.wikipedia.org

Replica del galeone Date Maru, o San Juan Bautista, a Ishinomaki, Giappone

Masamune had 16 children, two of whom were illegitimate, with his wife and seven concubines. He died in 1636 at the age of 69. In October 1974, Date Masamune’s grave was opened. Inside, along with his remains, archaeologists discovered his tachi sword, a letter box with a paulownia crest, and his armor. From the study of those remains, they determined Masamune to have stood 159.4cm tall, and having type B blood.

As legendary warrior and leader, Masamune is the character of various Japanese dramas. He was also played by the famous Ken Watanabe in the popular 1987 NHK series Dokuganryū Masamune.

Photo credits: wikimedia.org

La tomba di Masamune al mausoleo di Zuihōden

Japan History: Ishikawa Goemon

Ishikawa Goemon

Photo credits: data.ukiyo-e.org

Ishikawa Goemon (石川 五右衛門, 1558 – 8 Ottobre, 1594) è stato un fuorilegge Giapponese semi leggendario che rubava oggetti di valore ai ricchi per darli ai poveri. Proprio per questa sua caratteristica viene a volte definito il Robin Hood del Giappone. Esistono molte storie che lo vedono protagonista e che lo descrivono come un eroe popolare che si batte contro i potenti per i più deboli. L’autenticità di queste storie tuttavia non è sempre certa.

La sua prima apparizione negli annali storici si ritrova nella biografia di Toyotomi Hideyoshi del 1642 che lo descriveva semplicemente come un ladro.

Ci sono varie versioni della vita di Ishikawa Goemon. Secondo una di queste, egli nacque come Sanada Kuranoshin nel 1558 da una famiglia di samurai al servizio del clan Miyoshi della provincia di Iga. Nel 1573, quando suo padre, presumibilmente Ishikawa Akashi, fu assassinato dagli uomini dello shogunato Ashikaga, il quindicenne Sanada giurò vendetta. Cominciò quindi ad allenarsi nelle arti del ninjutsu a Iga sotto Momochi Sandayu. Allievo abilissimo ma di temperamento irruento, fu costretto a scappare quando il suo maestro scoprì la relazione di Sanada con una delle sue amanti.

Altre fonti gli danno il nome di Gorokizu, la cui provenienza viene individuata nella Provincia di Kawachi e non era un nunekin (ninja fuggitivo). Si era poi spostato nella regione del Kansai dove formò e guidò una banda di ladri e banditi come Ishikawa Goemon. Con questa banda rubava ai ricchi signori feudali, mercanti e clericali, condividendo poi il bottino con i poveri.

Secondo un’altra versione, che gli ha anche attribuito un attentato a Oda Nobunaga, sembra sia stato obbligato a diventare un ladro quando la rete organizzativa dei ninja fu distrutta.

Ciò che è certo è che Ishikawa Gomen divenne presto un personaggio popolare e apprezzato dal popolo, e non mancano gli aneddoti sulle sue avventure. Si dice che una volta, entrato in una stanza per compiere un furto, venne distratto dal sorriso di un bambino. Ishikawa cominciò a giocare con lui perdendo così il momento per mettere a segno il colpo. Un’altra storia riguarda il suo tentativo di assassinare il grande generale Oda Nobunaga. Una volta entrato nell’edificio di Oda, si nascose nell’attico proprio sopra la camera da letto del generale. Quando questi si fu coricato, Ishikawa praticò un buco sul soffitto proprio in corrispondenza della testa di Oda. Dal buco calò un tubicino tenendolo sospeso sopra la bocca del daimyo, tramite il quale fece passare un potente veleno. Ma il sonno di Oda Nobunaga era leggero e, svegliatosi, riuscì a sventare in tempo l’attentato.

Photo credits: wikipedia.org

Versioni molto conflittuali riguardano anche la sua pubblica esecuzione nell’olio bollente davanti al cancello del tempio Buddhista Nanzen-ji a Kyoto.

Secondo una prima versione, alcuni compagni di scorribande di Goemon furono catturati e costretti a confessare il nome del loro capo.

Una seconda versione afferma invece che Goemon provò ad assassinare Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Alcuni dicono che lo fece per vendicare la morte di sua moglie Otaki e la cattura di suo figlio Gobei, altri perchè lo shogun era ritenuto un despota. Entrato nella camera di Hideyoshi, nel castello di Fushimi, fu però scoperto dalle guardie perché urtò un tavolo facendo cadere una campanella. A volte si parla invece di un bruciatore di incenso magico capace di emettere un suono di richiamo. Fu quindi catturato e condannato a morire, gettato vivo nell’olio bollente in un calderone di ferro, insieme al suo figlio più giovane.

Ma se Goemon incontrò così la sua fine, le storie divergono sul destino del figlioletto. In alcune, Goemon riuscì a salvarlo tenendolo in alto sopra la testa, e il figlio fu poi perdonato. In altre invece, si dice che il padre all’inizio provò a salvare il figlio tenendolo sopra la testa ma, resosi conto della futilità del suo gesto, lo spinse sul fondo del calderone per ucciderlo il prima possibile. Rimase poi con il corpo del bambino sollevato in alto in segno di scherno verso i suoi nemici, fino alla morte per il dolore e le ferite.

Anche la data della sua morte è incerta, alcuni dicono che avvenne in estate, mentre altri la datano l’8 Ottobre, quindi in autunno. Prima di morire, Goemon lasciò un poema d’addio nel quale diceva che qualunque cosa fosse successa, al mondo ci sarebbero sempre stati dei ladri.

Una pietra tombale dedicata a lui può essere visitata ancora oggi nel Tempio Daiunin a Kyoto, mentre le tradizionali vasche verticali giapponesi, solitamente di ferro o legno, prendono ancora oggi il nome di goemonburo (Vasca di Goemon)

Teatro Kabuki e Cultura Popolare

Photo credits: img00.deviantart.net

Ishikawa Goemon è il soggetto di molte rappresentazioni teatrali kabuki. Quella che ancora oggi viene messa in scena è Kinmon Gosan no Kiri (Il Portale d’Oro e lo Stemma di Paulonia). Consiste in cinque atti scritti da Namiki Gohei nel 1778, di cui il più famoso è quello intitolato Sanmon Gosan no Kiri (Il Portale Sanmon e lo Stemma di Paulonia). In questo atto Goemon è visto seduto in cima al portale Sanmon del tempio Nanzen-ji. Sta fumando una pipa d’argento molto grande chiamata kiseru ed esclama “La vista primaverile merita un migliaio di pezzi d’oro, o così dicono, ma è troppo poco, troppo poco. Agli occhi di Goemon ne vale diecimila!” Goemon presto capisce che suo padre, un cinese chiamato So Sokei, era stato ucciso da Mashiba Hisayoshi e comincia a preparare la sua vendetta.

Il suo personaggio appare anche nel famoso racconto Quarantasette Ronin, messo in scena per la prima volta nel 1778. Nel 1992 invece, Goemon appare nella serie kabuki di alcuni francobolli postali Giapponesi.

Nella cultura popolare moderna ci sono in generale due modi in cui Goemon viene rappresentato: un giovane, scaltro ninja, o un potente bandito Giapponese.

Goemon è il personaggio principale della serie di video games Konami Ganbare Goemon dalla quale è stata tratta una serie televisiva. È anche il personaggio principale dei romanzi Shinobi no Mono e della serie di film ad essi ispirati, interpretati da Ichikawa Raizō VIII nel ruolo di Goemon. Nel terzo film, Shin Shinobi no Mono, conosciuto in inglese come Goemon Will Never Die, il protagonista sfugge all’esecuzione mentre un altro uomo viene buttato al suo posto nell’olio bollente. Goemon è anche il protagonista di alcuni film Giapponesi girati prima della seconda guerra mondiale come Ishikawa Goemon Ichidaiki e Ishikawa Goemon no Hoji.

Più recentemente invece, nel film Goemon del 2009 è interpretato da Yōsuke Eguchi e viene descritto come il più fedele seguace di Nobunaga assieme a Hattori Hanzō.

Il personaggio di Goemon appare anche in numerosi altri videogame come nella serie Samurai Warriors, Warriors Orochi, Blood Warrior, Kessen III, Ninja Master's: Haō Ninpō Chō, Shall We Date?: Ninja Love, Shogun Warriors, e Throne of Darkness. È anche una Persona iniziale in Persona 5 di Yusuke Kitagawa, e fa la sua comparsa anche nel drama taiga Hideyoshi, nel film Roppa no Ôkubo Hikozaemon, e nei manga Kaze ga Gotoku e Bobobo-bo Bo-bobo.

Ma forse il personaggio più conosciuto di tutti è quello di Ishikawa Goemon XIII in Lupin III (Rupan Sansei), diretto discendente del leggendario ladro e ideato dal mangaka Monkey Punch.

Japan History: Hattori Hanzō

Hattori Hanzō

Hattori Hanzō (服部 半蔵, ~1542 – November 4, 1596), also known as Hattori Masanari or Hattori Masashige (服部 正成), was a famous samurai of the Sengoku era. He is famous for saving the life of Tokugawa Ieyasu and then helping him to become the ruler of Japan.

Photo Credits: wonderslist.com/

Born the son of Hattori Hanzō Yasunaga (服部 半蔵(半三) 保長), a minor samurai in the service of the Matsudaira (later Tokugawa) clan. He would later earn the nickname Oni no Hanzō (鬼の半蔵, Demon Hanzō) because of the fearless tactics he displayed in his operations. This is to distinguish him from Watanabe Hanzo (Watanabe Moritsuna), who was nicknamed Yari no Hanzō (槍の半蔵 Spear Hanzō).

It is said that Hanzō started his training at the age of 8, on Mount Kurama situated north of Kyoto, became an expert warrior by the age of 12, and was recognised as a full fledged samurai at the age of 18.

He fought his first battle at the age of 16 (a night-time attack on Udo Castle). He later made a successful hostage rescue of Tokugawa's daughters in Kaminogō Castle in 1562, and went on to lay siege to Kakegawa Castle in 1569. He also served with distinction at the battles of Anegawa (1570) and Mikatagahara (1572). According to the Kansei Chōshū Shokafu, a genealogy of major samurai completed in 1812 by the Tokugawa shogunate, Hattori Hanzō rendered meritorious service during the Battle of Mikatagahara and became commander of an Iga Unit consisting of 150 men. In fact, he captured a spy of Takeda Shingen named Chikuan and when Takeda's troops invaded Totomi, Hanzō counter-attacked with only 30 men at the Tenryū River.

During the Tenshō Iga War, in 1579, he defended the ninja homeland in Iga province against Oda Nobukatsu, the second son of Oda Nobunaga. And again he valiantly fought in 1581, though unsuccessfully this time, to prevent the Iga province from being eliminated by forces under the personal command of Nobunaga himself.

But his most valuable contribution came in 1582 following Oda Nobunaga's death. In fact, he led the future shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu to safety in Mikawa Province across Iga territory with the help of remnants of the local Iga ninja. According to some sources, Hanzō also helped in rescuing the captured family of Ieyasu.

He served during the siege of Odawara and was awarded 8,000 koku. And by the time Ieyasu entered Kantō, he was awarded an additional 8,000 koku and had 30 yoriki and 200 public officials for his services. Ieyasu was said to have also begun to employ more Iga ninja with Hanzō as their leader.

Hanzō was known as an expert tactician and a master of spear fighting. Historical sources say he lived the last several years of his life as a monk under the name "Sainen" and built the temple Sainenji. Temple that was built to commemorate Tokugawa Ieyasu's elder son, Nobuyasu. Nobuyasu had been accused of treason and conspiracy by Oda Nobunaga and was then ordered to commit seppuku by his father, Ieyasu. Hanzo was called in to act as the official second to end Nobuyasu's suffering. Role that he refused to take on because he didn’t want to take the sword on the blood of his own lord. It is said that Ieyasu valued his loyalty after hearing of Hanzo's ordeal and said, "Even a demon can shed tears."

Some tales often spoke of him as possessing various supernatural abilities, such as teleportation, psychokinesis, and precognition. All these contribute to his continued prominence in popular culture. He died at the age of 55.

After his death, on 4 November 1596, Hattori Hanzō was succeeded by his son, whose name was also Masanari, though written with different kanji. He was given the title of Iwami no Kami and his Iga men would act as guards of Edo Castle, the headquarters of the government of united Japan. To this day, artifacts of Hanzō's legacy remain. Tokyo Imperial Palace still has a gate called Hanzō's Gate (Hanzōmon), and the Hanzōmon subway line.

Hattori Hanzō in modern culture

Photo Credits: bastardosenzagloria.com

As historical figure and as one of the protagonists of one of Japan's greatest periods for samurai culture, Hattori Hanzō has many admirer, both within Japan and abroad. In modern culture he is most often portrayed as involved with the Iga ninja clansmen.

Many films, specials and series on the life and times of Tokugawa Ieyasu depict the events mentioned above. The actor Sonny Chiba played his role in the series Hattori Hanzô: Kage no Gundan (Shadow Warriors), where he and his descendants are the main characters. His life and his service to Tokugawa Ieyasu is fictionalised in the manga series Path of the Assassin, while the young Hanzō is the main character in the manga Tenka Musō. The novel The Kouga Ninja Scrolls and its adaptations feature the four Hattori Hanzos serving as ninja leaders under the rule of Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Hanzō also appears in the novel Fukurō no Shiro (Owl's Castle), as well as in many manga. In the manga and anime series Gintama he appears as a parody character named Hattori Zenzo, while in the manga Naruto the character named Hanzō is the leader of a hidden ninja village of Amegakure. In Samurai Deeper Kyo,an unusual plot turn reveals that Hattori Hanzō is actually the real Ieyasu Tokugawa in disguise. He also appears in Tail of the Moon, and in the live-action film Goemon, other than in the episode "Spartan vs. Ninja" of the TV show Deadliest Warrior.

Hattori Hanzō appears as a recurring character in the Samurai Shodown video game series by SNK, appearing in every game in this series, as well as in its anime adaptation. He also has some guest appearances in The King of Fighters series. In World Heroes, another SNK video game series, Hanzō is one of the main characters along with his rival Fūma Kotarō. In the video game series Samurai Warriors, he is portrayed as a highly skilled ninja, highly loyal to Tokugawa Ieyasu. Hanzō is also featured in several other video games such as Taikou Risshiden V, Kessen III, Civilization IV: Beyond the Sword, Shall We Date?: Ninja Love, Pokémon Conquest, Sengoku Basara: Samurai Heroes, and the Suikoden series. In the limited edition of Total War: Shogun 2 he is the heir of the Hattori Clan, one of the factions fighting for supremacy over Japan, and has a DLC unit called "Hanzo's Shadows".

Some works, such as the trading card game Force of Will, the series Hyakka Ryōran, the anime series Sengoku Otome: Momoiro Paradox, and the video game Yatagarasu, reimagine him as a female ninja character.

In the film Kill Bill, Hattori Hanzō is the name of an incredibly skilled master swordsmith who creates letal swords. He is the one who created a special katana for the protagonist, although he had sworn to himself that he would never create instruments of death again.

Japan History: Samurai

Samurai

Photo credits: focus.it

The name Samurai comes from the verb saburau that means "to serve" or "to stand by one's side", literally "the one who serves". In Japanese, during the Heian period (794-1185), it was pronounced saburapi and later on saburai.

Another name used to refer to a samurai is bushi (武士). This word appeared for the first time in the Shoku Nihongi (続日本紀, 797 a.d.), an ancient Japanese document in forty volumes. It contains the most important decisions taken by the imperial court from 697 a.d. and the 791 a.d. A passage from the book says: "Samurai are those who build the values of the nation".

According to the book Ideals of the Samurai by William Scott Wilson, the words bushi and samurai became synonyms at the end of the XII century. Wilson fully explores the origins of the word "warrior" in the Japanese culture without overlooking the kanjis used to write it. He states that ‘bushi’ is actually translated with "the man who has the ability to maintain peace, with military or literary strength". Saburai was replaced by samurai at the beginning of the modern era, at the end of the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573-1603) and the beginning of the Edo period (the late 16th and 17th centuries).

Photo credits: focus.it

A Samurai served under a daimyo, local feudal lords who responded to the shogun. When the daimyo died or lost his trust in the samurai, the latter would become a Rōnin, or "wave man", in other words "free from constraints".

The bushidō code, the code of honour of samurai, required that to atone for one's crimes and regain honor a samurai had to resort to the practice of harakiri, that means "cutting the abdomen". Harakiri is the final act of the ritual suicide called seppuku, performed through the cutting of the abdomen with the short sword wakizashi. Violating these principles brought dishonor to the warrior that, as we said, became a rōnin, an errant samurai, adrift, without honor or dignity.

So, the meaning of the word rōnin had a negative connotation, and this was especially true in the Tokugawa era (1603- 1868), the period of greatest isolation and splendor of Japan. In this period many rōnin roamed the countrysides intimidating the peasants and plundering villages, in search of a new lord to serve.

A rōnin was ready to work from anyone paying him, or be willing to associate with other rōnin creating an havoc. They were despised by proper samurai and no one would be called to account for the killing of one of them. But rōnin also had another role. In fact, it was not unusual for them to join merchants, peasants and artisans to defend the villages from bandits, teaching them military tactics and martial arts. They were a sort of self-organised body guard (yojimbo).

It is believed that the yakuza, the modern Japanese mafia, was born from this sort of private police. In fact its members share with the ancient samurai a strong sense of belonging to the clan and an undivided loyalty toward their “boss”.

Here are some of the words used as synonyms of samurai.

•Buke 武家 - member of a military family;

•Mononofu もののふ - archaic word for "warrior";

•Musha 武者 - abbreviation for bugeisha 武芸者, literally "man of the martial arts";

•Shi 士 - sino-japanese pronunciation of the kanji commonly read as samurai

•Tsuwamono 兵 - archaic word for "soldier", made famous by a well-known haiku of Matsuo Basho. It indicates an heroic person.

Photo credits: samurai-archives.com

Their training started at the age of 3, and till 7 years old it consisted in learning not to be afraid of death and fighting by controlling their minds and bodys, and to obey to the orders of their master. To toughen their body, they were subject to cold showers under waterfalls or in the snow. This enabled them to resist to external stimuli. Then, they were taught how to use the bow and the sword against imaginary enemies. At the age of 12 they were already able to kill.

The bond with the master could become very special. In the feudal period, sexual practices among men were very common for samurai warriors. According to the translation of the shudo - from wakashudo (the "way of youths") - the pupils spent many years with older men. Men that not only taught them fighting skills but also introduced them to the world of eros. Apprentices would then become their official lovers, in a fully recognised relationship that so required absolute loyalty.

A samurai worked for the daimyō's glory, but their pay consisted in rice. To keep their social status, those samurai who were not born from a rich family relied on secondary works like making small umbrellas or toothpicks. But they made others sell them in their place so not to be compromised themselves. They also had many privileges: for example they could have a surname, something that commoners of the time couldn’t have in Japan. They also had the privilege of the kirisute gomen, or in other words the "right to cut and leave behind". A samurai had the right to kill anyone of inferior status who dared to disrespect them. The only concern was to prove, in a legal debate, that they had been wronged.

Regarding their private and love life, the wife was chosen through an arranged marriage. She had to have a warrior’s lineage, or else be “adopted” into a samurai family to ennoble her origins before the marriage.

But a samurai wife also had a “privilege” (euphemistically speaking): with marriage they too acquired the right to commit the ritual suicide, the jigai, by cutting the throat.

In medieval Japan it was not uncommon to meet samurai women that since their early childhood had been trained according to the values and the martial arts of the warrior class. Samurai of this class practiced martial arts, Zen, the cha no yu (tea ceremony) and the shodō (art of the calligraphy).

In the Tokugawa era they lost their military function and many of them became simple rōnin. By the end of the Edo period samurai had become bureaucrats serving for the shōgun or a daimyō, and their sward was just a ceremonial weapon indicating their status. With the Meiji restoration and the opening of Japan to the west in the XIX century, the samurai class was abolished because it was now considered outdated. Instead, a Western-style army was favored. Two laws, under the Meiji Emperor (1852-1912), marked the end of samurai. One, the Dampatsurei edict, forced warrior servants to give up their topknot haircut to use a western style haircut. The other, less "facade" and even more decisive, was the Haitorei edict, which deprived them of the right to carry weapons in public. To samurai without their katana remained nothing but a small state pension and the refuge provided by folklore.

But bushidō still survives in today's Japanese society.

The weapons

Photo credits: cdn.history.com

Photo credits: cdn.history.com

Samurai used a large variety of weapons, and indeed a clear difference between European cavalry and samurai concerns the use of weapons. A samurai never believed that there were disgraceful weapons, but only efficient and inefficient weapons. The use of firearms was a partial exception to this, as it was strongly discouraged during the 17th century by the shogun Tokugawa. It came to forbid them almost completely and to distance them from the training of most samurai.

In the Tokugawa period the idea that the katana contained the soul of the samurai started to spread, and samurai are sometimes (though erroneously) described as totally dependent on the sword to fight.

When they had reached the age of thirteen year old, boys of the military class were given, in a ceremony called genpuku, a wakizashi (the sword also used to commit suicide) and an adult name. In other words they became vassals and so official samurai. This gave them the right to bring a katana with them, though it was often secured and closed with laces to avoid unmotivated or accidental drawing. Together, the katana and the wakizashi, are called daishō (literally "big and small"). Their possession was an exclusive privilege of the buke, the military class at the top of the social pyramid.

Bringing this two swords was forbidden in 1523 by the shogun to ordinary citizens who were not sons of a samurai. This was decided in order to avoid armed rebellions since before the reform everyone could become a samurai.

But other than the sword, another very important weapon for a samurai, was the shigetou, the Japanese asymmetrical bow, and this was not modified for centuries until the introduction of gunpowder and musket in the 16th century. The shigetou, 2 meters long and made of laminated and lacquered wood, was a weapon exclusively used by samurai. Until the end of the thirteenth century the way of the sword (kendo) was less considered then the way of the bow by many bushido experts. A Japanese bow was a very powerful weapon: its dimensions allowed to fire with accuracy various types of arrows (such as flaming arrows or signal arrows) at a distance of one hundred meters. They even reached up to two hundred meters when precision was not needed.

During the period of samurai’s greatest power, the term yumitori (archer) was used as an honorary title for warriors even when the art of the sword became predominant. Japanese archers (see the art of the kyūjutsu) are still strongly associated with Hachiman the god of war.

Photo credits: nihonjapangiappone.com

The bow was usually used on foot from behind a tedate, a large wooden shield, but it could also be used on horseback. The practice of shooting while riding a horse became a shinto ceremony called yabusame. In the battles against Mongol invaders, these bows represented a decisive weapon as opposed to the smaller bows and crossbows used by the Chinese and the Mongols.

In the fifteenth century the spear (yari) became a popular weapon. The yari started to replace the naginata when individual heroism became less important on the battlefield and militias were more organized. In the hands of foot soldiers or ashigaru it was more effective than a katana, especially in open-field charges. In the Battle of Shizugatake, where Shibata Katsuie was defeated by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the so-called "Shizugatake's Seven spears" played a crucial role for the victory.

To complete their armament there were war fans with knife-like edges, but for many periods of Japanese history samurai were the only ones allowed to carry weapons.

Seppuku

Photo credits: focus.it

Seppuku (切腹) is a Japanese term that indicates the ritual suicide performed among samurai. The word harakiri (腹 切 り) is often used in western terminology. In Italian it is sometimes mistakenly pronounced as "karakiri", with an erroneous pronunciation and incorrect transcription of the ideogram ‘hara’.

More specifically, there are some differences between seppuku and harakiri, as explained below.

The literal translation of the word seppuku is "cutting the stomach", whereas for harakiri is "cutting the abdomen" and this act was carried out following a rigidly codified ritual. It was a way to atone for one’s crimes or to escape a dishonorable death by the hand of the enemies. A key element to understand this ritual is the following: the belly was believed to be the seat of the soul. The symbolic meaning of this act was therefore to show to the attendees one’s own soul without fault and in all its purity. But even this extreme gesture of pride and freedom of a samurai followed rigidly codified rules.

The sacrifice had to be consumed in front of witnesses using a dagger (tantō) or the short sword (wakizashi) and executing a "L" cut that, starting from the navel, proceeded from left to right and then upwards.The fingers of the feet bent downward guaranteed that the dying man on his knees would fall forward, covering the blood and guts. The presence of witnesses and of a kaishakunin, the assistant that had the responsibility to finish off the wounded man with a blow at his neck, assured that the victim did not suffer any further (and did not have any second thoughts).

The kaishakunin was the samurai’s trusted companion who, as promised to his friend, would behead him as he had wounded his abdomen to ensure that the pain did not disfigure his face and preserve his honor.

Often voluntarily practiced for various reasons, during the Edo period (1604-1867) it became a death sentence that did not lead to dishonor. In fact, given his position in the military class, the man sentenced to die was not executed but invited or forced to take his own life with a dagger by cutting his own abdomen so severely that it caused his death.

The beheading (kaishaku) required extraordinary skill and in fact the kaishakunin was the most talented swordsman among his friends. Indeed, a mistake caused by poor skills or by emotion would have caused considerable further suffering. The presence of the kaishakunin and consequent decapitation represent the essential difference between seppuku and harakiri. In fact, although the way the abdomen is cut are similar, in the harakiri the man committing suicide is not expected to be beheaded. Therefore, casting aside all the ritualty of the act, it results in an event of lesser solemnity.

The most well-known case of collective seppuku is that of the "forty-seven rōnin", celebrated in the play Chushingura, while the most recent case is that of the writer Yukio Mishima in 1970. In the latter example, the kaishakunin Masakatsu Morita, overwhelmed with emotion, repeatedly failed at severing Mishima's head, and it required the intervention of Hiroyasu Koga to behead the writer.

One of the most accurate descriptions of seppuku is that contained in Algernon Bertram Mitford's Tales of Old Japan (1871), later on resumed by Inazo Nitobe in his book Bushido, The Soul of Japan (1899).

In 1889, with the introduction of the Meiji constitution, it was abolished as a form of punishment, but cases of seppuku were registered at the end of World War II among officers, often from the samurai class, who did not accept Japan’s surrender . Another famous case of seppuku was that of the former daimyō Nogi Maresuke who committed suicide in 1912 after receiving the news of the emperor’s death.

By the name of jigai, seppuku was traditionally performed by women of the samurai class as well. In this case, after tying feet together to avoid disgraceful positions during the agony, they did not cut their belly but the throat.

The weapon used could be the tantō (knife), although more often the choice fell on the wakizashi, especially on the battlefield, and for this reason this blade was also called the "guardian of honor".

Photo credits: wikipedia.org

The Bushidō code

The Japanese warrior lived and died following a strict code of conduct, the bushidō code (the way of the warrior), which governed the unique and inseparable relationship between the samurai and his daimyō. At the core of this code there was absolute loyalty, a rigid definition of honor and the sacrifice of the good of the individual in favor of common good. This was also the ethics behind the actions of Japanese kamikaze during the Second World War, and the same ethics can be traced down to some modern Japanese companies. If an offense or a serious fault had crippled this relationship, there was always one way to save honor: seppuku or harakiri, the ritual suicide.

Samurai's principles were heavily influenced by the main spiritual and cultural currents that coexisted in the country. Towards 1000 Shintoism was still the main source of inspiration for samurai schools that emphasized loyalty to the emperor in an era in which being a samurai meant to be a capable warrior. Subsequently, however, Taoist, Buddhist, and Confucian ideas began to spread and overlap each other. In particular, after the Chinese Buddhism, Zen Buddhism and esoteric Buddhism experienced a great widespread as well. The latter was mainly practiced among the richest and most powerful noble houses, while zen Buddhism was also practiced by small schools and among rōnin. In this era, many schools that believed it was a samurai’s duty to perform his obligations not only to the best of his abilities, but also with grace and elegance, started to spread. This meant that a samurai had to show his superiority through his gestures. This way of thinking, that often encountered some resistance in the sixteenth century, resisted in many schools of samurai.

The warriors of the 900 a.d. had become, before the 1300, sophisticated poets, patrons, painters, art lovers, and porcelain collectors, codifying in many bushido related works (up to the Book of the Five Rings) a precise necessity. In fact, a samurai had to be skilled in many arts, not just in the use of the sword. The first big codification that embodied this important turning point was the Heike Monogatari, the most famous literary work of the Kamakura period (1185-1249). This work attributed to the way of the warrior the obligation to find balance between military force and cultural power. The heroes of this epic narration (the story of a fight between two clans, the Taira and the Minamoto), and others inspired by it in the following years, are gentle and well-dressed, they take care of their hygiene and are courteous with the enemy in periods of truce. But they are also skilled musicians, competent poets, scholars, sometimes especially well-versed in calligraphy or the arrangement of flowers. And more, they were enthusiastic gardeners, often interested in Chinese literature. Also, dying, they often put their epitaph in verse.

This dual nature of a samurai's duties had a remarkable widespread, until it became hegemonic. Hojo Nagauji (or Soun), lord of Odawara (1432-1519), one of the most important samurai of his time, wrote in the Twenty-One Samurai Precepts: "The way of the warrior must always be both cultural and martial. It appears unnecessary to remind that old laws state that cultural arts should be held in the left hand and martial arts in the right". These words seem to emphasized a certain predominance of martial arts, but following this teaching many samurai became famous swordsmans as well as experts in the tea ceremony, or artists, actors in the Nō theater and poets. Imagawa Royshun (1325-1420), a great commentator on Sun Tzu's ‘The art of war’, went even further stating that "Without knowing the way of culture, you will not be able to achieve victory in the martial path." Royshun had thus created a new idea of balance between culture and war known as bunbu ryodo ("never abandon the two ways").

Miyamoto Musashi himself, one of the strongest duellists of the seventeenth century, became, in the second part of his life, one of the most talented painters of that period. He agreed with Takeda Shingen (1521-1573), perhaps the greatest commander of the sixteenth century, who claimed that the greatness of a man depended on the practice of many ways.

This attitude obviously caused a whole series of harsh criticisms. In particular, we must mention Kato Kiyomasa's aversion (1562-1611) to everything that was not martial, and his opinion, shared by many "extremely martial" schools, was that a samurai devoted to poetry would become "effeminate", while a samurai who was also an actor or was interested in Nō theater should have committed suicide for the dishonor he was bringing upon his name.

"Extremely martial" way of thinking and a refusal of the cultural aspects of the samurai figure spread out in the following centuries. This may seem paradoxical for a time of peace (the so-called Pax Tokugawa) during which etiquette was not only accepted in small dojo, but it was also studied thoroughly. At the same time, however, there was a clear intention to return to the original meaning of being a samurai, a fearless warrior.

The different sources of cultural inspiration to which samurai were subjected (shintoism, esoteric shintoism, Taoism, Chinese Buddhism, pure earth Buddhism, Zen Buddhism, Esoteric Buddhism, Chinese Confucianism, Confucianism of Japanese glossators and Japanese classical epics) created different schools of thought and practice. Sometimes they followed opposing principles of life, but more often they were simply complementary, also thanks to the great attitude to pragmatism and the syncretism that characterizes Japanese culture.

Photo credits: wikipedia.org

Symbol of all martial arts. In the classical iconography of the warrior, cherry blossoms represented the beauty and caducity of life and were therefore revered. The sakura, when in full bloom, show a lovely sight in which the samurai recognised the magnificence of his figure wrapped in his armor. But it takes just a sudden storm to make all the flowers fall to the ground, as a samurai can fall by the sword of his enemy. The warrior, accustomed to the idea of dying in battle not as a negative thing but as the only honorable way to part with the world, reflected this philosophy in the cherry blossom .

An ancient verse still known today says "Among flowers the cherry blossom, among men the warrior" (花 は 桜 木人 は 武士 hana wa sakuragi, hito wa bushi), or "as the cherry blossom is the best among flowers, so the warrior is the best among men."

Japan History: Minamoto no Yoshitsune

Minamoto no Yoshitsune

Photo credits: wikipedia.org

Photo credits: wikipedia.org

Yoshitsune was the ninth son of Minamoto no Yoshitomo, and the third child he had with Tokiwa Gozen. Yoshitsune's childhood name was Ushiwakamaru (牛若丸). Shortly after his birth, Heiji's rebellion broke out, and his father and his two older brothers lost their lives. While his older brother Yoritomo, now the designated heir of the clan, was exiled to the province of Izu, Yoshitsune was entrusted to Kurama temple, in the mountains of Hiei near Kyoto. He was then put under the protection of Fujiwara no Hidehira (藤原秀衡), head of the powerful branch of the Fujiwara clan in the North (Northern Fujiwara), and brought to Hiraizumi, in the Province of Mutsu.

Photo credits: wikimedia.org

Photo credits: wikimedia.org

In May 1180, the son of Emperor Go-Shirakawa, that was supported by the Minamoto clan, issued a statement urging the Minamoto to rise against the Taira. The context is that of the Genpei War (1180-1185) which saw the clans Taira and Minamoto fight for the choice of the rightful Emperor to be put on the throne and thus secure control over the Country. The Battle of Uji was the beginning of a 5-year war during which Yoshitsune and Yoritomo met again after their separation in 1160.

In 1184 Yoshitsune went against his cousin Yoshinaka. Yoshinaka had taken control of the Minamoto clan after defeating the Taira in June of 1183. At that point, Yoritomo sent his brother Yoshitsune against Yoshinaka, who had obtained in the same year the position of Sô-daisho (general of the army). Yoshinaka's troops were defeated and, as soon as he learned that, he abandoned Kyoto along with Tomoe Gozen, the only example of female samurai warrior. He was soon cornered at Awazu and committed suicide. With Yoshinaka out of the way, Yoritomo secured the support of Go-Shirakawa to continue the war with the Taira. On March 13 Yoshitsune moved to Settsu, and his first objective was a Taira fortification, Ichi no tani.

Yoshitsune led in battle 10,000 men attacking from the West, while 50,000 men led by Noriyori, Yoshitomo's brother, attacked from the East. On March 18 Yoshitsune arrived in Mikusayama, attacking at night. According to the Heike Monogatari, the surviving defenders fled to the coast and passed over to Shikoku, leaving 500 dead. Yoshitsune then sent 7,000 men under Doi Sanehira down to the western side of Ichi no tani while he led the remaining 3,000 men down the top of the cliffs. The Minamoto won over the Taira, and their victory cleared the way for an assault on Yashima, the Taira headquarters on Shikoku.Yoritomo opted for a cautious approach. The next six months were spent consolidating the gains already made and sorting out the families who had thus far supported the Minamoto.

After Ichi no tani, Yoshitsune and Noriyori returned to Kyoto and paraded the Taira heads taken through the streets. In the following October Noriyori was dispatched to destroy Taira adherents on Kyushu, and began a long and tiring march through the western provinces. Yoshitsune stayed in Kyoto acting as Yoritomo’s deputy there into early 1185. Officially, he was responsible for issuing decrees ordering the termination of any violence within Minamoto territory. In practice, his directives covered various other issues, including the forbidding of war taxes without the express consent of the Minamoto leadership.

During Yoshitsune’s time in Kyoto the rift between him and Yoritomo became evident. It seems that Yoritomo had denied him the titles that the imperial court had granted Yoshitsune, and that he became furious when the court proceeded and approved the titles anyway.

In March 1185, with Noriyori preparing to invade Kyushu, Yoshitsune was authorized to return to the war. Intending to launch an assault on Yashima, he assembled a fleet of ships at Watanabe. During the preparations he argued with Kajiwara Kagetoki, one of his elder brother's closest retainers, about strategy, but in the night of March 22 Yoshitsune ordered to his men to set sail. Since the weather was extremely bad many sailors refused to go to sea, and departed only after Yoshitsune threatened to kill any man who disobeyed his orders. Even still, not all of the ships followed him.

Yoshitsune landed on Shikoku at dawn and set out for Yashima. The Taira base was situated on the beach and Taira Munemori, alerted by fires set nearby by Yoshitsune’s men, ordered an immediate evacuation of the fort. He himself fled to the ships with Antoku, the child Emperor protected by the Taira. Nonetheless, the Taira clan was completely eradicated in what is remembered as the battle of Dan-no-ura, one of the greatest battles of Japanese History.

After this victory, in 1192 Yoritomo was granted the title of Shogun. However, by that time, Yoshitsune was already dead because Dan-no-ura marked not only the ultimate recognition of his ability and fame, but also his tragic end. In fact, for a long time the relationship with his brother had been turbulent. And probably, the jealousy for the skills demonstrated so far by Yoshitsune played a role in Yoritomo's choice to declare his brother a threat to the Minamoto clan and the Empire itself.

Photo credits: wikimedia.org

After attempting to oppose Yoritomo, Yoshitsune was forced to find shelter at Mutsu, where there was his old guardian Fujiwara Hidehira. But Hidehira died in November 1187 leaving a will stating that Yoshitsune was to act as governor of Mutsu. A wish Hidehira's son, Yasuhira, ignored completely. A conflict broke out with the Fujiwara and inevitably the Kamakura authorities learned of Yoshitsune’s location. Benkei, Yoshitsune’s retainer and loyal companion, managed to hold off their assailants long enough for Yoshitsune to kill his young wife and commit suicide. The head of Yoshitsune was transported to Kamakura, where it provoked an emotional response from those who viewed it.

He was buried in the shintoist temple of Shirahata Jinja, in Fujisawa, where his remains are still guarded.

Myths and legends

In spite of all, information about Yoshitsune's death have always been a bit elusive. According to the Ainu historical accounts, he did not commit seppuku, but fled to Koromogawa taking the name of Okikurumi/Oinakamui.

In Hokkaido, the temple of Yoshitsune was erected in his honor in the town of Biratori. Some theories see him run away to Hokkaido and resurrect as Genghis Khan. But of course these are just legends.

Photo credits: samurai-archives.com

A remarkable soldier and a classical tragic figure, Yoshitsune was a legend even before his passing. Kujô Kanezane, a supporter of Yoritomo, wrote in his diary in 1185:

"Yoshitsune has left great achievements; about this there is nothing to argue. In bravery, benevolence, and justice, he is bound to leave a great name to posterity. In this he can only be admired and praised. The only thing is that he decided to rebel against Yoritomo. This is a great traitorous crime."

The manner in which Yoshitsune died assured him an honorable place in posterity, while the memory of Yoritomo will forever bear a black mark. What happened in those summer months of 1185 will always be a mystery. But it is certain that Yoshitsune’s achievements in the Gempei War changed the course of Japanese history and earned him a place among the greatest samurais.

Yoshitsune’s life in literature and in modern era

In spite of his military abilities, Yoshutsune’s life met his end in a bloody way that inspires sympathetic response among many people. In Japanese, the expression Hougan’biiki (判官贔屓), that means ‘sympathy and benevolence for the underdog’, includes Yoshitsune’s posthumous name, Hougan (判官). This name was given to him thanks to the position that Emperor Go-shirakawa had granted him, in fact, another way to pronounce the word is Hangan, that means ‘magistrate’.

Furthermore, Yoshitsune’s life is considered to be heroic to the point of being narrated. Legends and tales with this theme grew in number as time passed, and so Yoshitsune’s fame took a shape that was far away from its original historical self. Among the many legends, well-known is the one about his encounter in Oobashi with the strong Musashi. Or the one in which, thanks to shaman Kiichi Hogen’s daughter’s help, he was able to steal 2 legendary volumes of military strategies, Rikuto e Sanryaku, and study them. Or even more, the one about the sudden death of Benkei, warrior monk, loyal servant and friend, that died still standing on his feet in the Battle of River Koromogawa. These legends grew in popularity among a wide audience in the Muromachi period, about 200 years after his death, thanks to ‘Yoshitsune’s Chronicle’.

In fact, Yoshitsune appears as the protagonist of the third section of the Heike Mongatari, the classic tale that narrates the Genpei War events and that inspired many later works, especially in No and Kabuki tradition. In particular, it is said that his victory in the Sunaga battle had been due to his studies on the Tiger Book, contained in the Rikuto scroll, and that since that moment, that same book became essential for future victories. In later periods, Yoshitsune’s name was used to legitimize the glory of a lineage. For example, there is a martial arts school that is supposed to have inherited its technique from Yoshitsune himself or from the one that is considered his mentor, Kiichi Hogen.

MOON SAGA and MOON SAGA 2

Yoshitsune's figure was also portrayed by Japanese singer and actor GACKT in the theatrical plays MOON SAGA and MOON SAGA 2. He himself interprets Yoshitsune describing him as a mononofu, a half-human and half-demon being. GACKT, with his exceptional interpretative skills, was able to portray this duality perfectly, giving life, in the first part, to an ironic, funny and somewhat awkward character that in the second part becomes demonic and scary. The adventures of Yoshitsune are, in this case, fictionalized and mixed with a bit of supernatural elements, but they still tell his story, because Yoshitsune was like that. A duality, a character full of contrasts in which benevolence alternated with cruelty. Probably, Yoshitsune used to lose control completely when facing danger and for that reason he’d unleash his "demon" side.

MOON SAGA 2 was also the first theatrical representation in the world to use the projection mapping.

Photo credits: gackt.com

Photo credits: gackt.com

Japan History: Maeda Keiji

Maeda Keiji

Photo credit: wikipedia.org

Maeda Toshimasu, (1543-1612) also known as Maeda Keiji or Keijiro, was a Japanese samurai who lived in the Sengoku Period (1467-1568).

Born in Nagoya, he was the son of Takigawa Kazumasu, who was later adopted by his uncle Maeda Toshihisa, brother of Maeda Toshiie. He served under Oda Nobunaga with his uncle and was initially the heir of the clan. However, Nobunaga replaced Toshihisa with Toshiie as head of the Maeda family, and Toshimasa lost this position. At that point, the disagreements between him and his uncle Toshiie began, and it is said that they often quarrelled.

In 1581, he made a reputation for himself under his uncle’s command in a conflict in the Province of Noto. During the Battle of Komaki-Nagakute, three years later, Toshimasu saved Sassa Narimasa when he was attacked at the Castle of Suemori.

In Kyoto, he met Naoe Kanetsugu the karō (samurai and senior advisors at a daimyō service) of Uesugi Kagekatsu. The two of them became friends and Toshimasu joined the Uesugi clan in the invasion of Aizu. The invasion failed, and Keiji led the rearguard during the retreat.

In the battle, however, he was able to give a splendid show of force riding on his inseparable horse Matsukaze, 'the wind among the pines', while brandishing his spear. Due to Keiji’s actions, the Uesugi's forces were able to retreat intact, while the samurai returned to the capital devoting himself to art and literature.

He was later barred from Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s campaign in Kyushu for his wild behaviour. But when Tokugawa Ieyasu challenged the Uesugi clan in 1600, Keiji once again fought with them.

In the battle against the Mogami, legend says that he succeeded in breaking the enemy lines with only eight riders, shattering their formation.

After the Uesugi clan retired in the Yonezawa Domain, Toshimasu remained with them.

According to the legend, after Keiji’s death, his horse Matsukage, that shared with his master the same indomitable personality, ran away never to be found again. It was a magnificent horse that no one else but Keiji had been able to tame, and so powerful to carry his master’s large frame.

It is still possible to see Keiji’s armour at the Miyasaka Museum.

Photo credit: wikipedia.org

Keiji - Hana no Keiji

Photo credit: vignette3.wikia.nocookie.net

The character of Keiji Maeda was so characteristic and so eccentric that he was chosen as the protagonist of a series of manga, Keiji ( 花の慶次 - Hana no Keiji). The story is written by Keichiro Ryu and drawn by Tetsuo Hara, better known for his other work, Fist of the North Star.

Photo credit: Google images

The manga tells the adventures of the greatest kabukimono that ever existed in Japan. A kabukimono is an eccentric person who loves to stand out from others for his behaviour and his appearance, and who has the ultimate goal of imposing his will on others.