Japan History: Furuta Shigenari

Furuta Shigenari (Motosu District, Gifu Prefecture, 1544 - July 6, 1615) was a Japanese warrior who lived during the Sengoku period. He was the son of tea ceremony master Furuta Shigesada (known by his Buddhist name Kannami, later renamed Shuzen Shigemasa) who was also one of the younger brothers of the lord of Yamaguchi-jo Castle in Motosu-gun County, Mino Province. While pursuing a career as a warrior, Oribe also acquired a sophisticated taste for the tea ceremony from his father and seems to have been adopted by his uncle.

Furuta Shigenari, the samurai who was also a master of the tea ceremony

Author: SaiKaiAngel

photo credit: https://it.wikipedia.org/

Furuta Shigenari became Oda Nobunaga's servant when Nobunaga attacked the Mino province in 1567. In 1569, Shigenari married Sen, one of the younger sisters of Nakagawa Kiyohide (the lord of Ibaraki-jo castle in Settsu province).

In 1576, Oribe became an administrator of Kamikuze no sho (now, Minami-ku Ward of Kyoto City), Otokuni-gun district, Yamashiro province. He later joined Hashiba Hideyoshi's (later Toyotomi Hideyoshi) army during the attack on Harima Province and Akechi Mitsuhide's army during the attack on Tanba Province, making a successful career as a war leader despite his small salary of 300 koku.

As a master of the tea ceremony, he is widely known as Furuta Oribe. His common name was Sasuke, his first name was Keian. The name 'Oribe' as master of the tea ceremony originated from the fact that he was awarded the rank of Junior Fifth Rank, Lower Grade, Director of Weaving Office.

During the period of his union with Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Furuta Shigenari met master Rikyū and became one of his favourite pupils for about ten years during which he wrote two works: Oribe Densho ("The Book of Secrets") and Oribe Hyakka ("The Hundred Precepts"). His relationship with Rikyū was so intense that he was not afraid to disobey the common lord Hideyoshi when Rikyū left in exile for Sakai. During Toyotomi Hideyoshi's rule, the generation of tea masters of the Nobunaga period, Yamanoue Sōji, Sen no Rikyū, Tsuda Sogyu, Imai Sokyu, died out in a few years. All the tea masters were philosophical and political opponents of the military expansionism of warlords such as Hideyoshi, and the importance of the discipline of tea placed them in great social and political authority, so, like Rikyu, they were exiled or forced to commit suicide. The art of tea, once Nobunaga's generation ended, became a state ceremony in the Tokugawa Restoration period and Furuta Shigenari became the most important tea master of the new generation. He also taught the shōgun Tokugawa Hidetada, Kobori Enshū and Honami Kōetsu. However, accused of plotting a conspiracy against the Tokugawa, he was ordered to commit seppuku in 1615.

The influence

Furuta Oribe's influence encompassed all ceremonial practice from the practice of tea preparation, to artistic and architectural styles, furniture and the style of ceramics.

In fact, Oribe-ryū was the style of ceremony he oversaw, as was the style of Oribe-yaki ceramics. He also designed a type of lantern (tōrō) for the tea garden, known as Oribe-dōrō.

Here comes the Kimono Experience at TENOHA Milano

Here comes the KIMONO EXPERIENCE with Giappone In Italia, Milano Kimono and TENOHA Milano!

The Giappone In Italia Association has created a unique experience in collaboration with Milano Kimono and TENOHA Milano, we are talking about the KIMONO EXPERIENCE!

Feel the real Japan with the Kimono Experience

Author: SaiKaiAngel

Do you feel like spending some unique, timeless moments? At a time when everything is hectic, why don’t we take a moment for ourselves? Without commitments, stress or confusion? Let's immerse ourselves in the love of Japan and do it in the best possible way! Have you ever wondered "But how would I look in a yukata or a kimono?" I think so, at least, I've asked myself that many times and finally managed to see myself in traditional Japanese dress! As you know, Giappone In Italia Association, TENOHA Milano and Japan Italy Bridge are working with a common focus: building a bridge between Japan and Italy by promoting Japanese culture here.

An absolutely special experience that will allow you to feel in Japan. If you can't take the plane, how can you experience Japan? You can do it as always in the corner of Japan here in Italy, TENOHA Milano! Not only that, from 15 to 30 June, you can enjoy the "KIMONO EXPERIENCE"! What is it about exactly?

What is it?

The KIMONO EXPERIENCE is an exhibition at TENOHA Milano from 15 to 30 June, featuring the most beautiful kimonos and photos by Alberto Moro, President of Japan in Italy and author of the book 'Il mio Giappone'. You will find photos of people who wanted to wear kimonos in the streets of Milan even without being Japanese! This is the aim of KIMONO EXPERIENCE, to make non-Japanese people live the emotion of the Rising Sun, not only around, but also on them. Yes, because if you book your place, you can have the joy of wearing a yukata and being photographed by none other than the President of Japan in Italy, Alberto Moro, who is, as you know, also a famous photographer.

Imagine yourself in the Japanese atmosphere, wrapped up in a yukata (kimono summer version) that the dressmaker Yurie Sugiyama will have you put on, photographed by Alberto Moro in the incredible and Japanese TENOHA Milano. A dream? No! A reality that is waiting for you!

You can visit the exhibition from 15 to 30 June, from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m., in the TENOHA Milano pop-up space at Via Vigevano 18.

If you would like to dress up and have your photo taken in yukata, remember that the dress-up teacher Yurie Sugiyama will be available from 17 to 20 and from 24 to 27 June, from 10.30 am to 1 pm and from 3 to 6 pm. Although the fitting will be free of charge, in the form to be filled in below, you will be asked for a booking deposit which will be returned when you show up at the KIMONO EXPERIENCE!

Not only that! If you wish, you can buy your photo in kimono as a unique and unrepeatable souvenir of the day. They will surely ask you when you flew to Japan, because these are moments that can hardly be repeated here in Italy.

KIMONO EXPERIENCE, un’esperienza da non perdere, per portare nuovamente il Giappone In Italia, come recita il nome dell’Associazione che l’ha creata.

Obviously we at Japan Italy Bridge look forward to seeing you there!

>> BOOK NOW YOUR KIMONO EXPERIENCE! <<

Subject to availability.

photo credits: Alberto Moro, Presidente Associazione Giappone in Italia

Japan History: Fukushima Masanori

Fukushima Masanori (1561 - August 26, 1624), whose name was originally Ichimatsu, was born in Owari Province.

Fukushima Masanori, one of the Seven Spears of Shizugatake

Author: SaiKaiAngel

photo credit: wikipedia.org

Son of Fukushima Masanobu, Fukushima Masanori was a Japanese general and daimyō in the service of the Tokugawa, also famous for being one of the Seven Spears of Shizugatake. It is also said that he may have been a cousin of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Masanori stormed Miki Castle in Harima Province and, during the Battle of Shizugatake in 1583, defeated Haigo Gozaemon and had the honour of taking the first head, that of the enemy general Ogasato Ieyoshi.

Fukushima Masanori took part in many of Hideyoshi's campaigns; it was after the Kyūshū campaign (1586-1587) that he became daimyō, receiving the fief of Imabari in Iyo province; shortly afterwards he took part in the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592-1598) and distinguished himself once more during the Battle of Chungju.

Following his involvement in the Korean campaign, Masanori was involved in the search for Toyotomi Hidetsugu. He led 10,000 men in 1595, surrounded the Seiganji temple on Mount Kōya and waited for Hidetsugu to commit suicide. On Hidetsugu's death, Masanori received Hidetsugu's former fief of Kiyosu in Owari province.

Being hostile to Ishida Mitsunari, Fukushima Masanori came into sympathy with Tokugawa Ieyasu; Ishida burned Masanori's castle on a pretext and during the Battle of Sekigahara launched the first attack on Ukita's troops, remaining in the front line throughout. Having won the battle and captured Ishida, Masanori beheaded the enemy daimyō in Kyoto along with Anko and Konishi. Masanori received the fief of Hiroshima in Aki, but Ieyasu never fully trusted Masanori, so he ordered him to rebuild the Nagoya castle so that he could spend some of his income.

At that point, Masanori asked to take part in the siege of Osaka (1614-15), but was forced to remain in Edo. The new Shōgun, Hidetada, trusted Masanori even less and, after Ieyasu's death, accused him of misrule and transferred him to the fief of Kawanakajima. Fukushima Masanori's younger brother Masayori had already been deprived of his fief at Yamato in 1615.

Il posto di comando di Fukushima Masanori a Sekigahara

photo credit: samurai-world.com

It seems that his descendants became hatamoto in the service of the Tokugawa shogunate. The hatamoto were samurai under the direct control of the Tokugawa Shogunate in feudal Japan. All three shogunates in Japanese history had direct contacts, only in earlier shogunates they were called gokenin. However, in the Edo period, the hatamoto were the senior vassals of the Tokugawa dynasty and the gokenin were the junior vassals.

Fukushima Masanori owned one of the three great spears of Japan: Nihongo, or also called Nippongo (日本号). Used in the Imperial Palace, the Nihongo was later owned by Masanori Fukushima, and then passed into the hands of Tahei Mori. It was recovered, restored and is now in The Fukuoka City Museum.

Japan History: Chōsokabe Motochika

Chōsokabe Motochika (1538 - 11 July 1599) was a Japanese daimyō of the Sengoku period and was born in Okō Castle in the Nagaoka district of Tosa province. The eldest son of Chōsokabe Kunichika, Chōsokabe Motochika was such a sweet boy that his father was worried about his nature, and it seems he was nicknamed Himewako, "Little Princess", by his vassals.

Chōsokabe Motochika, also known as Himewako

Author: SaiKaiAngel

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Despite these concerns, Chōsokabe Motochika proved to be a skilled and brave warrior in his first battle, defeating the Motoyama clan in 1560 at the Battle of Tonomoto. After defeating the Motoyama and forming alliances with local families, Chōsokabe Motochika was able to build his power base on the Kōchi Plain. While remaining loyal to the Ichijō, Motochika with a force of 7000 men marched on the Aki clan, rivals of the Chōsokabe, defeating them in 1569 during the Battle of Yanagare. At that point Chōsokabe Motochika could concentrate on the Ichijō.

During the rule of the Hata district of Tosa, Ichijō Kanesada was a very unpopular leader and because of this, Motochika wasted no time in marching on the Ichijō headquarters in Nakamura and in 1573 Kanesada fled. At that point, the Ōtomo clan provided Kanesada with a fleet and with that he returned, leading an expedition that the Chōsokabe defeated at the Battle of Shimantogawa. At this point Kanesada submitted to the Chōsokabe, who probably had him assassinated in 1585.

Chōsokabe Motochika became the sole ruler of Tosa, and one of the problems the Chōsokabe faced was their own territory. Because of his poverty, he was unable to pay his generals, so he began to look to neighbouring provinces.

The unification of Shikoku

After the conquest of Tosa, Chōsokabe Motochika prepared for an invasion of the province of Iyo, against the lord of that province Kōno Michinao, a daimyō who had been driven from his domain by the Utsunomiya clan, helped only by the Mōri clan. But at this time the Mōri clan was at war with Oda Nobunaga, so they were unable to help Michinao, however the campaign in the Iyo province was not easy.

In 1579 a Chōsokabe army of 7000 men, led by Hisatake Chikanobu, attacked Okamoto Castle, held by Doi Kiyoyoshi in southern Iyo. During this siege, Chikanobu was killed and his army defeated. Motochika returned the following year with some 30,000 men to Iyo and forced Michinao to flee to Bungo province. With the Mōri and Ōtomo engaged on other fronts, Motochika was free to continue his conquest of the island and in 1582 was able to continue his raids on the Awa province to defeat the Sogo clan, giving him control of the island in 1583.

photo credits: mvbennett.wordpress.com

In 1579 Chōsokabe Motochika entered into communication with Nobunaga who seemed to have praised him, although in private he referred to him as a bat on a birdless island and planned to conquer Shikoku in the future, planning to give it to his son Nobutaka. This did not happen, due to Nobunaga's death in 1582.

Involved in the ensuing dispute between Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu the following year, he promised Tokugawa his support, although he made no direct moves to that end. Hideyoshi instead sent Sengoku Hidehisa to block any interference from Motochika. The Komaki campaign between Hideyoshi and Ieyasu ended in a peace treaty, and in 1584 Hideyoshi invaded Shikoku with 30,000 troops from the Môri clan and another 60,000 from Hashiba Hidenaga. Motochika managed to retain control of the Tosa province thanks to the terms decided by Hideyoshi.

Chōsokabe Motochika is remembered both for his 100-article Code of Chōsokabe and for his tenacity in founding a very strong castle-city from Oko to Otazaka and then to Urado. However, the problems caused by Morichika's appointment as heir led to the clan's undoing. After Nobuchika's death in battle, Hideyoshi suggested that Motochika's second son, Chikakazu, be appointed heir.

But when Motochika resigned, he made Morichika, his fourth son, his heir, because he felt Chikakazu was physically incapable of assuming leadership of the family. With this in mind, Chikakazu retired and died of illness in 1587. When Chōsokabe Motochika was called to Hideyoshi's invasion of Kyūshū, he and Sengoku Hidehisa were called in.

Their mission was to raise the siege of the Ōtomi clan. Despite the wise advice of Chōsokabe Motochika, generals Ōtomo and Sengoku did not adopt a defensive position and attacked the forces of the Shimazu clan at the Battle of Hetsugigawa, defeating the allied troops, but at the same time Nobuchika, Motochika's heir, died. At that point Toyotomi Hideyoshi praised Motochika's thinking and offered him Ōsumi as compensation for his loss, but this was refused.

In 1590 Motochika led a naval contingent in the siege of Odawara and in 1592 commanded 3000 soldiers in the invasion of Korea. On his return from Korea he retired to Fushimi, became a monk and died on 11 July 1599.

Sakura, an in-depth look at the flower symbol of Japan

We continue our series of in-depth articles dedicated to the Japanese culture and today we talk about Sakura, the flower symbol of the Rising Sun. "The perfect flower is a rare thing. One could spend a lifetime looking for it, and it would not be a wasted life."

Sakura 桜 Symbolic flower of Japan

Guest Author: Flavia

This is how Ken Watanabe began in a scene from the famous film 'The Last Samurai' (2003) as the rebel samurai Katsumoto, against the backdrop of a beautiful Japanese garden. How could we not remember this scene from the film which, despite some historical inaccuracies, is able to give us moments like this. Surrounded by splendid trees in bloom, Katsumoto-Watanabe is simply staging the prototype of Japanese aesthetic sensitivity towards nature. In this case, towards flowers. But here we are talking about one flower in particular... the cherry blossom, an undisputed object of age-old admiration: the Sakura (桜 - さくら).

We are all familiar with cherry blossoms: their beauty is obvious, admiring them a natural consequence. This, I would say, needs no explanation. We can, however, talk about the particular importance of this delicate little flower in Japan, so much so that it has become a "moral" symbol (the official one is the chrysanthemum).

The term 'Sakura' refers to both the flower and the tree - known as the 'Japanese cherry tree' - a type of cherry tree characteristic of the Far East. There are about a hundred varieties of Sakura in Japan, including the big cities. But the most common are the Yamazakura and especially the (Somei-) Yoshino, with its typical pale pink-white colour, which has been admired by the Japanese for hundreds of springs.

photo credits: japan.stripes.com

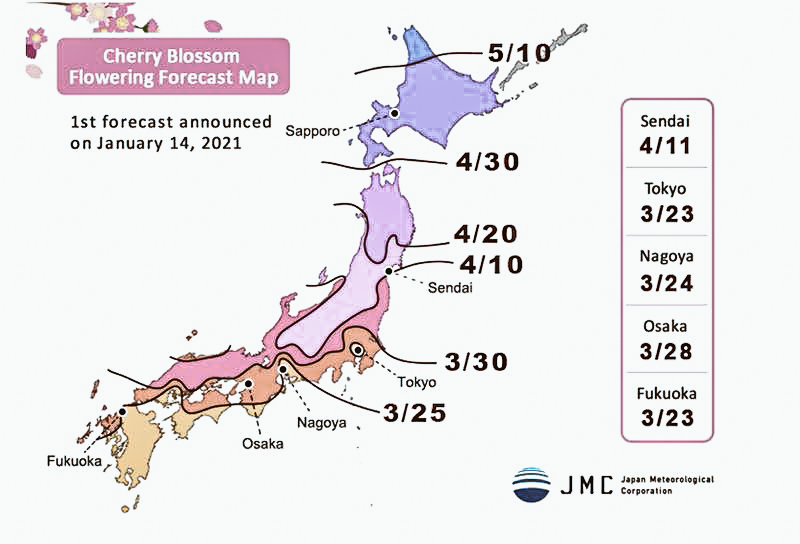

The Sakura is an institution in Japan, with its own special symbolism and deep meaning. It appears on the famous 100 yen coin and frames Fuji san, Japan's other great symbol, on the back of the current 1000 yen note. It is so popular that the National Meteorological Agency issues a special Sakura Zensen ( 桜前線 ) bulletin every year to update on the status of the flowering. The media informs the population daily about the best spots, so that they can adjust for the beloved Hanami (flower-gazing) activity, deciding where and what variety of Sakura to see.

Flowering proceeds from south to north, as the climate is milder in southern areas. So if you arrive in Japan when the flowering has already passed in the centre-south, look at the calendar, you might still be in time to catch them in Hokkaidō!

Mankai 🌸 Flowering

The average flowering time varies according to geographical location, but in any case it is short: a few days, maximum ten days. It starts in Okinawa, around the end of January, gradually moving northwards with the last buds opening around mid-May in Hokkaidō. This is the approximate time period. Bad weather, disturbances or sudden changes in temperature can obviously affect the duration of flowering, given the extreme delicacy of the little flower. It all depends on the climate and the year: it can happen that the flowers bloom a little earlier or later, or that the blooming is interrupted by a sudden change in climate. The time of the flowering boom is known as Mankai (満開), which in fact means 'full opening'.

photo credits: japan.stripes.com

As mentioned above, most cherry trees are of the Somei-Yoshino variety, but there are over a hundred species. Some are even capable of producing edible fruit. Of the criteria for distinguishing between the different types, the most immediate is undoubtedly the number of petals, which can be ten, twenty or even more. The most common are the classic five-petalled Sakura, both wild and cultivated.

🌸 Types of Sakura

But let's look at some examples of more unusual cherry trees. In addition to Somei-Yoshino, the most cultivated and popular, we can find:

- Yama-zakura (山桜), the 'Mountain Cherry'. Very popular, it ranks right after Somei-Yoshino in terms of popularity. It has large pink buds and five petals.

- Fuyu-zakura (冬桜), or "Winter Sakura". As the name suggests, it is a cherry tree that begins to blossom in autumn and continues in winter, although not continuously.

- Yae-zakura (八重桜), the "Double Cherry Tree". So called because of its 'reinforced', i.e. very full-bodied, bud with more than five petals. It is associated with the ancient capital Nara (奈良).

- Shidare-zakura (枝垂桜), i.e. "weeping cherry tree" because its branches fall, like a willow, creating a cascade of pink flowers. It is the official flower of the Kyoto prefecture.

- Ichiyō (一葉), "a leaf". It owes its name to a leaf-like pistil that emerges from its centre when fully open. It is one of those that can have 20 to 40 petals.

photo credits: Akemi K on Flickr, medigaku.com, Pinterest

Ippon-zakura (一本桜) are defined as all cherry trees planted "in solitude". These include Japan's three great cherry trees, the Sandai-zakura (三大桜). The trio consists of the Jindai-zakura in Yamanashi, the Usuzumi-zakura in Gifu and the Takizakura in Fukushima. Jindai and Usuzumi belong to the Edohigan variety (from which Yoshino is also derived), while Takizakura is a weeping cherry tree. In particular, the Jindai-zakura, located in the Jissōji temple (實相寺), is perhaps the oldest in Japan: it is about two thousand years old and has a circumference of 13 and a half metres!

Spring (春), season of hope

The act of contemplating trees in blossom dates back to the Nara period (8th century). Initially the prerogative of the imperial court of Kyoto, over the centuries it was extended first to the category of samurai and then to the rest of the population. Let us say that in the beginning it was the plum tree (梅-Ume) that was the object of attention. The plum tree represented the link with China, as it originated there. But already in the Heian period (8th-12th centuries), due to the interruption of relations with Middle Earth, the Ume was ousted by the more autochthonous Sakura. From then on, spring-themed poems began to refer to Sakura even only as "flowers" (花-Hana) and the word "Hanami" also became interchangeable with "sakura". Linguistic details, however, are indicative.

Spring (春- Haru) has always been characterised as a symbol of rebirth, of generating power.

In ancient times, the blossoming of cherry trees was associated with prosperity, as it presaged an abundant rice harvest. In order to propitiate a good harvest the following year, the beginning of the planting season was opened with a series of rituals ending with joyful celebrations under the Sakura. In the 18th century, Shōgun Yoshimune Tokugawa further promoted this custom by planting Sakura trees in various areas.

Today, spring is the season for students, graduates and undergraduates, who rely on the auspiciousness of the blossom. April marks the start of the new school year for students, while graduates and many school leavers are preparing to enter the world of work. April also marks the start of the new fiscal year in Japan. In short, the cherry blossom season brings with it some beginnings in that land. Therefore, it is duly celebrated with the Sakura Matsuri (桜祭り) festival.

photo credits: Pinterest, Pinterest

Sakura in sweets and delicacies

Sakura and spring are also celebrated through food, in keeping with good Japanese tradition. Famous is the Hanami Bentō (花見弁当), or the bentō that is a must during a picnic under the cherry blossoms. For those who don't know, the bentō is a box for a picnic lunch, used by the Japanese all year round, but in this period it has a Sakura theme. You might find Sakura Onigiri (桜おにぎり) in there, for example, rice balls with salted Sakura on top.

However, there is also cherry blossom tea (桜茶, Sakura-cha), possibly combined with Sakura-Mochi (桜餅), a typical rice cake with red bean paste, wrapped in a salted cherry leaf. Sakura infusion is offered to newlyweds on their wedding day as it is considered a good omen. Wagashi (和菓子) - the traditional Japanese confectionery - come in a variety of sakura-themed varieties. Again, among the more commercial products: just as you can have Matcha-milk, there is also an all-pink Sakura-milk. And we could go on and on, but perhaps we'd better stop, otherwise our mouths will water too much!

photo credits: kitchenbook.jp, pinterest.fr

Hanami (花見), admire the buds

Hanafubuki (花吹雪): "snowy storm of buds". This is how the spectacle of falling petals from cherry trees in bloom is defined, whose rain colours the landscape in a kind of "spring snowfall". If one of these petals (花びら- Hanabira) falls into one's sake glass while making Hanami, it is a propitiatory sign of good health.

As mentioned at the beginning, the word "Hanami" means the practice of looking at cherry blossoms (花= flower(s), 見= watching). Nowadays, Hanami celebrations can range from simple picnics to more elaborate celebrations with music and entertainment. They can also take place at night, in which case, we talk about Yozakura (夜桜) or "sakura by night". The result, you can imagine: an evocative nocturnal Hanami, amid paper lanterns and moonlight.

photo credits: power-shower.com

However, the peculiarity of Hanami is not in simply witnessing this spectacle of nature: it is in assisting it by capturing its fleeting appearance. The beauty of the buds also lies in their transience. In those who contemplate them, a feeling of sweet melancholy arises... which the delicacy of these flowers is able to evoke when, having detached themselves from the tree, they float carried by the wind or a delicate breeze, to then settle on the ground. An emotion given by the realisation that this is nothing other than the ultimate nature of human existence itself: destined, sooner or later, to have an end.

"So I come to this place with my ancestors and a thought comes back to me: like these sprouts we are all dying... recognising life in every breath, in every cup of tea, in every life we take away... " [ Katsumoto Moristugu - The Last Samurai ]

photo credits: YouTube

Symbolism of Sakura: mono no aware (物の哀れ)

The symbolism of Sakura is therefore both sweet and bitter, but this should not surprise us, as we are familiar with the Japanese feeling of "Mono no aware". In other words, a "pathos for things" characterised by a delicate hint of nostalgia, due to the awareness of their constant change. A concept that our Sakura embodies to perfection and of which he inevitably becomes the spokesman. Its beauty is enchanting but evanescent, ephemeral. So contemplation becomes sweet because of the delicacy of the flower, but also melancholic... because it is aware of its evanescence. Thus we contemplate its splendour but with an aftertaste of sadness. In a few words, this is the essence of Sakura.

Once again we are faced with an aesthetic that transcends the exterior. An exterior whose beauty hooks individuals, then leads them to a wider form of contemplation. We have seen this well, also in our article dedicated to Wabi-Sabi 侘寂. This has never been more true than in the case of the Sakura.

Cherry blossoms thus symbolise the transience of life and cyclicity. Because they blossom in all their glory, but their show remains for a limited time. The transience of life, youth and beauty: a metaphor that nature itself seems to want to offer every year and which Japan has been particularly careful to capture. At the same time, however, they are also a symbol of (re)birth and hope... because every year they come back to bloom in all their splendour.

Wonderful and a symbol of vitality on the one hand, extremely fragile on the other: this is their dual nature. Given this awareness, the reference to Buddhism is inevitable.

Symbolism of Sakura: other meanings

Other more specific meanings attributed to Sakura have to do with the number 5. So, naturally, it is the classic five-petalled cherry tree that best lends itself to this type of symbolism. The number 5 is said to recall the Japanese cosmogonic myth (about the birth of the 'cosmos'), according to which there were originally two gods, Izanagi and Izanami, who fathered five children; the birth of the fifth child, the god of fire, would prove fatal to the mother-goddess Izanami. Izanagi, distraught, thus killed this son, from whose parts the mountain gods would then originate. The number 5 also refers to the Japanese esoteric Buddhist concept of the five orientations (cardinal points plus the centre) and the five elements of water, fire, earth, ether and vacuum.

More generally, cherry trees can also be associated with clouds simply because of a visual issue: their mass blossoming can be reminiscent of clouds in the sky. A bit like the expression 'Hanafubuki' we saw earlier, where fubuki (吹雪) alone means 'snowstorm'.

photo credits: Flavia

As the Sakura, so the Samurai

But back to our Katsumoto-Watanabe, his sentence actually ended with "...this is Bushidō". In fact, Sakura was also associated with the ideal of the way of the warrior and the figure of the samurai (侍), so much so that it became the emblem of the category. You will say, where is the similarity? In the fact that the cherry blossom embodied the qualities typically associated with the samurai (courage, purity, honesty, loyalty...). As the Sakura dies at the height of its splendour, so the samurai at the height of his vitality and strength was ready to die if the time came. In this sense, his life, however grand, was as fragile as that of a cherry blossom. However, he was not afraid of death, since it was experienced as a last ideal act and the only possible honourable end, in the name of extreme loyalty to his values.

In the cherry tree, the bushi (warrior) found his model and identified his life with it. Just like the delicate little flower, he had to lead his existence giving his all, through dedication in every gesture, until his last sigh. All that mattered was to "burn" as much as possible through that fuel, which was his life force. In all this, there could be no room for the fear of death. On the contrary, it was in the warrior's last moments that his beauty shone brightest.

So the Sakura, so the bushi: just like in the proverb "Hana wa sakura-gi, hito wa bushi" ( 花は桜木-人は武士 ) that is "Among the flowers the cherry tree, among the people the warrior". The samurai in battle could fall under the blows of the opponent, just like buds that fall to the ground detached from the branches by a gust of wind or rain. Just like so many small, triumphant buds, the samurai flourished, only to meet their fate.

photo credits: Pinterest

This identification was also used in various ways by Imperial Japan centuries later. Among others: the Sakura was reproduced on the sides and in the name itself of the Ōka ( 桜花 ) airplanes to symbolise the extreme act of the Tokkōtai (Special Attack Unit) Kamikaze at the end of World War II. The pilots themselves, on the verge of their suicide mission, are said to have embarked carrying a cherry branch.

Nowadays, the Sakura may symbolise the martial arts.

"Woman sitting under the cherry blossom trees"

photo credits: appareassociazione.blogspot.com

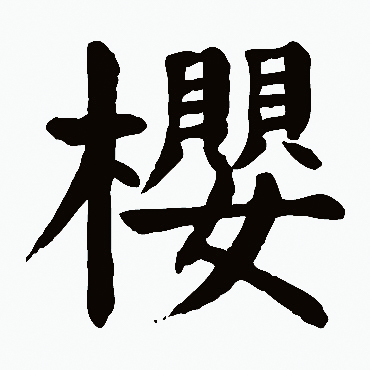

This is the image that could be drawn - certainly the one I see - by observing the ideogram of "sakura". This is far from being the explanation why the kanji 桜 has this specific form, but it lends itself well to such an interpretation. Especially given its present simplified form. Before leaving us, we cannot conclude without a parenthesis on the writing and the cherry tree kanji.

As you can see in the picture above, Sakura's ideogram 桜 is composed on the left of the radical 木 (=tree), on the right of three dashes with the character 女 (=woman) below. The little part in pink, tell the truth: doesn't it really resemble the petals of a flower?

Actually, this part used to be written in a more elaborate way and had nothing to do with the meaning. It was written like this: 櫻. Later on, it underwent a process of simplification, like so many other ideograms in both Japan and China (where they come from). Bearing in mind that ideograms derive from pictograms, let us observe our character in its transition from pictogram to ideogram in the images below.

photo credits: shufam.hao86.com, shufa.m.supfree.net

This was its transition, and then in more modern times it changed exactly as follows: 櫻 🡪 桜 (in China it became 🡪 樱 ). The double 貝貝, which preceded the present three hyphens, indicated "necklace"; while the single 貝 still means "shell". So you see how, by investigating the Chinese etymology, the real historical evolution is revealed. Be careful, however, because the whole right-hand side (i.e. 嬰) of the ideogram 櫻 has reason to be there solely for a phonetic reason. (Not for reasons of meaning, which is also different between Chinese and Japanese). That is, that part has been "put" there to give the pronunciation to the kanji 櫻 as a whole.

But beyond this brief digression, we still like to see it like this: like a little woman under a flowering tree. Right? Since we are dealing with the simplified character today, we can safely indulge in this reading of the kanji which, coincidentally, is very reminiscent of the image of a woman under the blossoming cherry trees. And it certainly helps a lot to remember the ideogram. After all, this flower also recalls femininity. It is no coincidence that Sakura, or the variant Sakurako (桜子or 櫻子), are quite common female names in Japan.

photo credits: pinterest.it

Japan History: Azai Nagamasa

Azai Nagamasa (1545 - 26 September 1573) was a Japanese daimyō, son of Azai Hisamasa, from whom he inherited the leadership of the clan in 1560 when Hisamasa was forced to step down in favour of his son.

Azai Nagamasa, the head of the clan Azai

Autore: SaiKaiAngel

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Nagamasa became one of Nobunaga's enemies in 1570 due to the Azai's alliance with the Asakura clan, fighting against him in important battles including the Battle of Anegawa. Nagamasa and his clan were destroyed by Nobunaga in August 1573, and he committed seppuku during the siege of Odani Castle.

Conflict with Oda Nobunaga

Not only the arch-enemy of Oda Nobunaga, Azai Nagamasa also became his brother-in-law, as he married his sister Oichi in 1564. Oda Nobunaga sought to establish relations with the Azai clan because of their strategic position between the lands of the Oda clan and the capital, Kyoto.

The great conflict began when in 1570, Oda Nobunaga declared war on the Asakura family by besieging Kanegasaki castle. The Asakura and the Azai had been allies since ancient times. In this war, contrary to many who wanted to honour the alliance with the Asakuras, Nagamasa preferred to remain neutral, siding with Nobunaga. In the end, the Azai clan chose to honour their ancient alliance with the Asakura and came to their aid. Therefore Nobunaga's army, which was marching on the Asakura lands, retreated towards Kyoto. However, within a few months Nobunaga's forces were on the march again, but this time they marched on the Azai lands.

The Battle of Anegawa

In the summer of 1570, Oda Nobunaga returned to attack with Tokugawa Ieyasu and an army of around 30,000 men in Omi province against the Azai and Asakura. The Battle of Anegawa took place on two fronts, Oda against Azai, Tokugawa against Asakura. Although outnumbered, Nagamasa's troops managed to hold off the Oda troops and it seemed as if victory was assured, but when Tokugawa Ieyasu came to Nobunaga's aid after defeating the Asakuras, the situation was reversed.

Death

Over the next two years the Azai were under constant attack from the Oda, who came to besiege the castle of the capital, Odani in 1573 in the famous Siege of Odani. It is during this period that the Azai are seen to be loosely aligned with numerous anti-Oda forces, including the Asakura, Miyoshi, Rokkaku and various religious complexes.

With no way out, Nagamasa carried out seppuku in August 157e along with his father Hisamasa, sending Oichi and his three daughters to Nobunaga who decided to spare them. This did not happen with Nagamasa's only male heir, Manpukumaru, who was executed by General Toyotomi Hideyoshi on Nobunaga's orders.

Oda Nobunaga made sure that his sister, Oichi, was not informed of this, but she eventually came to this suspicion.

It seems that Nobunaga harboured a strong grudge against Nagamasa because of his alleged treachery, although it was he who broke the agreement first. It is also said that Nobunaga had the skulls of Nagamasa, Hisamasa and the Asakura chief lacquered so that they could be used as mugs, but this fact is not only not historically accurate, but could also be invented to further discredit Nobunaga's reputation.

photo credits: wikipedia.org

It should be added that Nagamasa's three daughters were of great importance, starting with the fact that they married very famous men:

- Chacha, or Yodo dono, was the second wife of Toyotomi Hideyoshi and mother of his heir Hideyori.

- Hatsu, married daimyo Kyōgoku Takatsugu.

- Oeyo, or Sūgen'in, was the wife of the second Tokugawa shōgun, Hidetada, and mother of his successor Iemitsu.

Samurai flags at the Tokyo Olympics

Samurai are still very respectable and important figures, so as the Tokyo Olympics approach, a content producer is hoping to spark greater understanding between nations with anime characters wearing traditional Japanese clothing.

Flags of countries revised as samurai for Olympics

Author: SaiKaiAngel | Source: The Japan Times

Kama Yamamoto along with other artists launched World Flags in 2018 with the idea of helping people around the world become familiar with their cultures in a fun way and says, "I want the project to be recognised globally as something that can unite the world through anime and samurai."

Yamamoto's idea is to use characters in samurai or traditional Japanese clothing to illustrate different nations, their flags and increase interest in Japan.

Here are some examples:

the Peruvian character Vargas is depicted as a ninja in red and white carrying a leaf-shaped kunai and, in the case of Chile, the condor, which is the national bird, is perched on the shoulder of a samurai, while the Canadian character wears a red and white kimono with a maple leaf on its sleeve.

Yamada says a lot of work is underway to get the initiative officially recognised by the Tokyo Games organisers.

Yamamoto's background is in educational personification books; he has drawn manga characters to represent jobs ranging from tapioca shop owners to web designers. The books are aimed at children and include information on average salaries and what it entails to better inform children about the choices available to them when they grow up.

photo credits: The Japan Times

The educational purpose remains with World Flags.

There were about 80 characters on the website at the beginning of December, according to marketing producer at Digital Entertainment Asset Hiroshi Tsuruoka. The site is regularly updated with new personified flags.

Characters are introduced on the project's official Twitter page as soon as they are ready. With over 15,000 followers, the page also boasts fan art posted by those inspired by the characters.

However, characters can undergo both physical and "personality" changes in line with advice or criticism from people around the world, helping them to become more suited to the country concerned.

In one case, the Spanish flag, whose character is called Iniesta, was initially portrayed as a bullfighter, but was later transformed into a flamenco dancer following criticism that bullfighting was a controversial topic in the country.

The project got what Yamada called its first "big break" in the summer of 2019, when the Chinese flag depicting Aaron was widely shared online. Yamamoto soon began receiving interview offers from Chinese media, along with offers to create a range of merchandise e.g. mouse pads that are currently available online.

The characters are illustrated by a group of artists brought on board by Yamamoto, many from his previous projects.

"Some of the illustrations are by full-time artists, but others are drawn by people ranging from housewives to vets who draw as a hobby," he says. The flags are assigned by Yamamoto, who brainstorms a rough idea of the character design, to individual artists based on their illustration styles.

photo credits: The Japan Times

While Yamamoto works to finish personifying all the countries, a number of people from smaller nations have expressed delight at finding their respective flags in samurai form.

Some, including Mexico and Venezuela, have even received framed images of their personified flags at their respective embassies in Tokyo.

"We believe that an anime-style character representing Mexico can be an ideal way to convey the long-standing friendship that exists between the Mexican and Japanese people," Emmanuel Trinidad, the cultural affairs adviser at the Mexican embassy in Tokyo, said in an email.

"Every comment received about it on social media seems to praise the fact that the work goes beyond any stereotypical image and instead presents a fresh and more modern approach to the characters representing the countries in general."

The project was first published as a book last year, with illustrations of the characters and information ranging from national demographics to the number of Olympic medals won by the nation in question.

They would also like to turn it into an anime or superhero movie in the future, with the characters joining forces to fight an enemy to save the world.

"The story will not have a protagonist, and all the characters will work together for a common goal," says Yamada.

Yamamoto initially hoped to complete the project in 2020 ahead of the Olympic Games before they were postponed due to the new coronavirus pandemic. Now he is aiming to present around 200 personified flags by the end of this year. will he be able to achieve his goal of uniting countries with Japan? we are sure he will. Let's look forward to it and enjoy these works in the meantime!

Japan History: Asakura Yoshikage

Asakura Yoshikage (12 October 1533 - 16 September 1573) was a Japanese daimyō of the Sengoku period (1467-1603) who ruled a part of Echizen province.

Asakura Yoshikage, head of the Asakura clan

Author: SaiKaiAngel

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Asakura Yoshikage was born in the Ichijōdani castle of the Asakura clan in Echizen province. His father was Asakura Takakage and his mother seems to have been the daughter of Takeda Motomitsu.

Yoshikage succeeded his father as head of the Asakura clan and lord of Ichijōdani Castle in 1548, demonstrating great skill in political and diplomatic management, especially through his negotiations with the Ikkō-ikki at Echizen. Thanks to them, Echizen enjoyed a period of relative peace compared to the rest of Sengoku-period Japan, becoming a place for refugees fleeing violence in the Kansai region. Ichijōdani even became a centre of culture modelled on the capital of Kyōto.

Ichijōdani Asakura Family Rovine storiche | photo credits: wikipedia.org

Conflicts with Oda Nobunaga

After his capture in 1568, Ashikaga Yoshiaki appointed Yoshikage as regent and enlisted the help of the Asakuras to drive Nobunaga from the capital. In 1570, Oda Nobunaga then invaded Echizen and succeeded in invading the castle due to Yoshikage's lack of military skill. Azai Nagamasa, Yoshikage's brother-in-law, attacked Nobunaga with the Asakuras at Kanegasaki, but Nobunaga withdrew his troops and managed not to be captured. At the Battle of Anegawa, Yoshikage and Nagamasa were defeated by the superior forces of the Oda and Tokugawa clans led by Nobunaga and Ieyasu.

Death

Yoshikage fled to Hiezan after the battle and attempted to reconcile with Nobunaga, which enabled him to avoid conflict for three years. In 1573, during the siege of Ichijodani Castle, Yoshikage was betrayed by his cousin, Asakura Kageaki, and was forced to commit seppuku at the age of 39. His death also destroyed the Asakura clan.