Japan Folklore: Miko

Miko (巫女)

"Vergini del tempio"

Photo credits: pinterest.com

Abbiamo visto questa figura in diversi anime: Rei Hino aka la coraggiosa Sailor Mars di Bishōjo senshi Sērā Mūn, la misteriosa Kikyō di Inuyasha, oppure le simpatiche gemelle Hiiragi di Lucky Star.

Tutti questi personaggi avevano in comune la stessa occupazione: erano miko, quelle fanciulle che si prestano a tuttofare nei templi Shintoisti gestendo varie funzioni. Troviamo quindi le miko impegnate ad aiutare il sacerdote nelle sue funzioni, a tenere pulito il tempio e a raccogliere le offerte dei fedeli.

Definire questa figura secondo canoni occidentali è molto difficile. Le miko non sono assimilabili alle suore Cristiane, né sono dei veri e proprio Sacerdoti, benché nello Shintoismo è possibile che tale funzione sia ricoperta anche da una donna. Sono più simili forse agli oracoli dell’antica Grecia, o a delle sciamane, dato che nell’antichità a loro era data la possibilità di comunicare con i kami, divinità Shintoiste. Entrando in trance, esse potevano intercedere presso gli dei per poi comunicare il loro volere agli uomini. Le loro doti divinatorie e la loro capacità di comunicare con il mondo degli spiriti erano riconosciute come volere Divino.

Le origini

Photo credits: dannychoo.com

La loro origine risale al periodo Jōmon, la Preistoria Giapponese, che va da circa il 10000 a.C. al 300 a.C. Una delle menzioni più antiche e storicamente accertate di qualcosa si simile alla parola miko si ritrova nel nome della regina sciamana Himiko (175 circa – 248). Ella era la regnante dello Yamatai, il più potente tra i regni in cui era suddiviso il Giappone arcaico. Non sappiamo però se Himiko fosse una miko o meno.

La parola ‘miko’ è composta dai kanji 巫 ("shamano, vergine non sposata"), e 女 ("donna"), e generalmente viene tradotto come ‘vergine del tempio’. Anticamente era scritto come 神子 “Bambino di dio” o “Bambino divino”.

La forte connessione con le divinità era data anche dal fatto che le miko ballavano il Kagura (神楽), letteralmente "Intrattenimento per gli dei o musica degli dei". Questa è un’antica danza sacra Shintoista che affonda le sue radici folklore giapponese legandosi alla dea dell’alba Ama-no-Uzume. Si dice infatti che la dea con questa danza riuscì a convincere Amaterasu, la dea del sole, ad uscire dalla caverna in cui si era rifugiata dopo aver litigato con il fratello Susanoo, il dio della tempesta.

La danza kagura veniva spesso presentata anche presso la corte imperiale da quelle miko che di fatto erano viste come le discendenti della dea Ama-no-Uzume.

Nell’antichità, le miko erano erano figure sociali essenziali, ed era questo un ruolo che prevedeva grossi impegni e responsabilità. La loro discendenza e connessione con il divino le identificava come messaggere del volere del kami, ma non solo. Le poneva infatti anche nella posizione di influenzare la vita sociale e politica, e di fatto quindi le sorti del villaggio presso cui prestavano servizio.

Attraversarono però una notevole crisi a partire soprattutto dal periodo Kamakura (1118-1333). Si cominciò infatti a porre un freno alle loro pratiche sciamaniche e le miko, senza più fondi, furono costrette a mendicare. Alcune scivolarono tristemente verso la prostituzione.

Dopo un periodo di grandi trasformazioni in epoca Edo, nel 1873, per volere del “Dipartimento degli Affari Religiosi” (教部), fu emanato un editto chiamato Miko Kindanrei (巫女禁断令). Esso proibiva ogni pratica spirituale alle giovani miko.

Come si diventava miko?

Photo credits: thirteensatlas.wordpress.com

Il percorso per diventare miko era lungo e difficile. Scelta dal clan in base alla propria forza spirituale o per discendenza diretta da una sciamana, la fanciulla iniziava la sua preparazione in giovane età, in genere con il primo mestruo. Ci volevano dai tre ai sette anni di per diventare una vera miko.

Le ragazze erano solite lavarsi in acque gelide, praticare l’astinenza, e compiere altri riti come atti di purificazione. Il tutto era volto a imparare a controllare il suo stato di trance.

Imparavano una lingua segreta che solo loro e gli altri sciamani conoscevano, e dovevano conoscere il nome di ogni kami rilevante per il loro villaggio. Imparavano anche l’arte divinatoria della chiaroveggenza e le danze per poter entrare in stato di trance e parlare con le divinità.

Al completamento di questo percorso si svolgeva una cerimonia che simbolicamente rappresentava il matrimonio tra la miko e il kami che avrebbe servito. Vestita con un abito bianco che ne rappresentava la vita precedente, la fanciulla entrava in uno stato di trance e le veniva chiesto quale kami avrebbe servito. Dopo di che, le veniva tirato un dolcetto di riso sul viso provocandone lo svenimento. Veniva poi adagiata in un letto caldo fino al suo risveglio, quando avrebbe vestito un kimono colorato per indicare l’avvenuto matrimonio tra lei e la divinità.

In virtù di questo legame con la divinità le giovani dovevano restare vergini. Ci sono state però miko con una particolare forza spirituale che hanno potuto continuare il servizio anche dopo il loro matrimonio.

Le miko oggi

Photo credits: muza-chan.net

Oggigiorno la figura della miko esiste ancora ma sono per lo più giovani ragazze universitarie che lavorano part-time presso il tempio. Assistono il kannushi o ‘uomo di dio’ nelle varie funzioni e riti del tempio, compiono danze cerimoniali, tengono pulito il tempio e vendono omikuji, fogli di carta cui è scritto una predizione divina. In genere non hanno bisogno di una preparazione specifica e non devono essere necessariamente vergini, anche se è ancora richiesto che siano non sposate. La danza kagura è divenuta una semplice danza cerimoniale e non più un mezzo per entrare in contatto con l’entità divina.

Il loro abito tradizionale e composto nella parte superiore da un haori bianco che ne rappresenta la purezza, e nella parte inferiore da un hakama, “pantalone” rosso fuoco. Rossi o bianchi sono anche i nastri che ne legano i capelli.

Durante le cerimonie usano campanelli, rametti di sakaki, o intonano preghiere suonando un tamburo. Tra gli altri oggetti rituali è presente anche lo azusa-yumi, un arco che veniva usato per cacciare via gli spiriti maligni. In passato usavano anche specchi per richiamare il kami o delle kataka.

Magari le miko hanno perso la loro connessione divina, ma non la tradizione millenaria che le lega alla cura del tempio, restando una delle figure femminili più famose del Giappone ancora ai giorni nostri.

Photo credits: pinterest.com

Japan Folklore: Botan Dōrō

Botan Dōrō

La Lanterna di Peonie

Photo credits: allabout-japan.com

Photo credits: allabout-japan.com

Esistono molte storie dove amanti sfortunati sono divisi dal destino, a volte arrivando insieme alla morte (Romeo e Giulietta e Tristano ed Isotta le più famose). Ma nessuna è come la storia Botan Dōrō o La lanterna di Peonie (牡丹燈籠). Due innamorati divisi dal regno dei vivi e quello dei morti sono indissolubilmente legati dal loro giuramento d’eterno amore.

Questa leggenda vede la luce nel libro Jiandeng Xinhua scritto da Qu You durante la prima parte della dinastia Ming. Successivamente, venne poi riproposta durante il periodo Edo dallo scrittore e prete buddista Asai Ryōi sull’onda del fenomeno Kaidan (怪談). Questo termine giapponese indica tutte quelle storie che narrano di mistero e fantasmi, scritto con due kanji: Kai( 怪)che significa “strano, misterioso, apparizione incantata” e Dan (談)“narrazione recitata”.

Questa leggenda va riconosciuta come una delle prime storie giapponesi riguardanti i fantasmi a diventare film nel 1910. Con numerose riedizioni durante gli anni, è forse una più produttive tra cinema, adattamenti televisivi e Pink Movie, genere Soft Porno Giapponese.

La bella Otsuyu

Photo credits: pinterest.com

Photo credits: pinterest.com

La leggenda narra che durante la prima notte dell’ Obon (la commemorazione dei defunti secondo la tradizione Buddista Giapponese) il samurai Ogiwara Shinnojo incontra una bellissima donna e una bambina sua serva. In mano le due hanno lanterne di peonie, come vuole l’usanza, e il samurai chiede alla bimba il nome della splendida donna. Otsuyu era il suo nome ed il samurai non fu in grado di fare altro se non innamorarsene perdutamente e giurarle amore eterno quella sera stessa. Da li in poi, tutte le sere i due si incontrano bruciando di passione l’uno per l’altra. Tuttavia, durante le prime ore del mattino la bella donna e la bambina sparivano. A causa di questo comportamento sospetto, ed anche per via di una malattia improvvisa dell’uomo, un anziano vicino si incuriosisce. Entrando in casa sua, scopre che il samurai non giaceva a letto con una bellissima donna ma con uno scheletro! L’anziano vicino avvisa dunque un prete che a sua volta avvisa Ogiwara, il quale scopre così che l’amata è in realtà un fantasma. Ogiwara capisce anche che la sua malattia era dovuta al fatto che dormire con uno spirito consuma l’energia vitale di una persona. Il prete benedice l’abitazione del samurai lasciando incantesimi protettivi e portafortuna affinché la donna e la bambina non possano più entrare. La sera stessa la donna cerca invano di raggiungere l’amato ma, non riuscendovi, urla disperata il suo amore per Ogiwara che alla fine cede lasciandola entrare in casa. La mattina dopo, il vicino ed il prete trovano Ogiwara morto stringendo a sè lo scheletro di Otsuyu.

Dallo stile macabro del periodo Edo al romanticismo di quello Meiji

Photo credits: tumblr.com

Photo credits: tumblr.com

Di questa storia è molto famosa la versione del teatro Kabuki, ma c’è una sostanziale differenza tra le due. Nella versioni teatrale infatti i protagonisti si conoscono prima della morte di Otsuyu. Le loro famiglie sono molto vicine da tempo e questo aveva favorito la nascita dell’amore tra i due. Questa versione è la più conosciuta proprio per il romanticismo pregnante dall’inizio alla fine. Il loro amore, la passione giovanile, e poi la delusione per un distacco forzato dovuto per un periodo alla malattia del ragazzo. Durante questo periodo di separazione Otsuyu muore convinta che Saburo non fosse sopravvissuto alla malattia. Saburo invece si riprende e disperato per la morte della ragazza prega il suo spirito durante la festa dell'Obon. Quella sera stessa, tornando a casa, incontra sul suo cammino una donna e la sua serva con in mano una lanterna di peonie. Con sua grande gioia il giovane si accorge che quella donna è proprio la sua Otsuyu che da quella notte in poi, tutte le notti, andrà a fargli visita. Ma la gioia durerà poco. Infatti, un servo, spiando da una fessura nel muro della stanza di Saburo, si accorge che in realtà egli giaceva ogni notte con uno scheletro. Un prete buddista viene subito avvertito e alle porte della casa vengono affissi dei talismani per impedire allo spirito di entrare. Eppure, ogni notte la fanciulla torna per gridare il suo amore per Saburo che, disperato per la nuova separazione, si ammala nuovamente. Ma la consapevolezza di amarla comunque e nonostante tutto significa una sola cosa. La morte! I talismani vengono rimossi per permettere allo spirito di entrare ancora una volta. L’ultima. Il giovane protagonista però muore felice tra le braccia di colei che ama.

Questa differenza di temi si può attribuire al diverso periodo in cui sono state scritte le due versioni. Quella originale risale al periodo Edo con la vena macabra che caratterizza il folclore Giapponese dell’epoca. Quella teatrale invece è più recente e vede la luce nel periodo Meiji, ovvero il periodo in cui il Giappone si avvicina all’occidente grazie all’apertura dell’imperatore Mutsuhito. Apertura che non si verificò solo a livello politico, ma anche a livello culturale influenzando quindi gusti e costumi, e questa leggenda ne è un esempio.

Japanese Culture: Il Ramen

Ramen: “Imperatore” della tavola Giapponese.

Photo credits: narutonoodle.com/

Fino a pochi anni fa, per amanti o meno della cucina etnica, andare al Giapponese equivaleva prettamente a gustare Sushi: piatto composto da pesce crudo e riso.

Questo piatto da colori e forme suggestive strizza l’occhio ai commensali più modaioli (ma non solo!), che hanno modo di gustare “prima con gli occhi che con la gola”. Ma ora un altro piatto famoso in tutto il Giappone è finalmente approdato anche sulle nostre tavole, facendo impazzire i più.

Il Ramen (ラーメン,拉麺 rāmen), forse vero e proprio piatto rappresentativo del paese. Talmente conosciuto in tutto il Giappone che vanta per ogni regione un suo modo diverso di farlo. Regione diversa, ricetta diversa. Gustiamole tutte allora …

Una zuppa ricca di ingredienti: spaghetti cinesi, carne di maiale, Nori (海苔) o alga secca, uova sode, e il kamaboko. Da noi conosciuto come surimi, la sua forma più famosa, quella a spirale, si chiama Naruto (come il personaggio del manga omonimo il cui nome è ispirato proprio a questo ingrediente) . Il brodo può essere di pesce o carne, varie guarnizioni e modi diversi di insaporire, con semi di sesamo o pepe, dal miso alla salsa di soia.

Storia di una Zuppa

Photo credits: travelcaffeine.com

Benché non sia chiaro quando ebbe inizio la diffusione di questo piatto in suolo giapponese, l’origine è cinese, visto che uno degli ingredienti base sono i mian o spaghetti cinesi di frumento. Va anche detto che in Cina solo negli ultimi anni c’è stata una riscoperta, non considerato più piatto tradizionale ma d’importazione giapponese. In Cina vengono chiamati rìshì lāmiàn “Lamian in stile Giapponese”.

Il Ramen è sempre stato un piatto da gustare fuori casa, e all’inizio del ‘900 c’erano numerosi chioschi da strada con gestori Cinesi. Poi, dopo la Seconda Guerra Mondiale, i soldati giapponesi di rientro dalla Cina, dove avevano appreso la tradizione culinaria, aprirono diversi ristoranti in tutto il paese. Da lì in poi, una continua evoluzione che ha portato a come si conosce il Ramen oggi giorno.

Così tanto amato che dal 1994 è stato aperto a Yokohama lo Shin-Yokohama Raumen Museum il museo interamente dedicato a questa prelibatezza.

Ramen da compagnia.

Photo credits: jpninfo.com

Come detto in precedenza, in passato non era poi così strano gustare scodelle di Ramen nei chioschi da strada, famosi anche oggi giorno sebbene non diffusissimi. Questo perché il Ramen è anche un cibo da strada da assaporare nei tradizionali Yatai, bancarelle mobili. I migliori ristoranti invece sono i Ramen-ya con pochi posti a sedere sia al banco che ai tavoli, ma con la finalità di mangiare solo Ramen.

E non è inusuale trovare piatti di Ramen in parchi divertimento o nei menù dei karaoke. Ci scappa anche che finito il lavoro tra colleghi si faccia un salto agli Izakaya, pub con la formula Nomihodai “all you can drink” e Tabehodai “all you can eat”. Qui, con un tempo massimo di tre ore, i commensali tra liquori ed altri cibi possono gustare anche il Ramen con un menù dal prezzo fisso.

Menzioni d’onore e le regionali.

Photo credits: zerochan.net

Benché la ricetta classica sia comune in tutto il Giappone ci sono varianti sempre innovative.

Qui va menzionato il Ramen Blue , di un bellissimo e brillantissimo colore, e vogliamo anche dirlo del tutto naturale! Ma questa è un'innovazione estrema.

Le varianti “classiche” regionali sono:

- Quella di Tokyo con tagliatelle spesse in brodo di pollo al gusto soia, con guarnizione di germogli di bamboo, scalogno, maiale a fette, spinaci alghe, un uovo e un po’ di Dashi. Da provare nei quartieri di Ikebukuro, Ogikubo e Ebisu.

- A Sapporo è famosa per la versione “invernale”, con talvolta frutti di mare, burro, maiale, mais e germogli di fagioli.

- Yokohama ha il le-kei , uovo alla coque dove il commensale deve indicare la morbidezza desiderata per poi romperlo ed insaporire il brodo con cipolla, maiale, spinaci e alga.

- Kitakata con tagliatelle spesse ma piatte, servite in brodo di maiale.

- Hakata con brodo composto da osso di maiale, e con spaghetti sottili, zenzero, aglio, verdure in senape e semi di sesamo.

Se leggendo questo articolo vi è venuta una gran fame vogliamo lasciarvi alcuni indirizzi dove poterlo gustare qui in Italia:

Nozomi

Via Pietro Calvi 2, 20129 Milano, Italia

+39 02 7602 3197

http://www.nozomi.milano.it/

Casa Ramen

Via Porro Lambertenghi 25, Milano, Italia

+39 02 3944 4560

https://www.facebook.com/casaramen

Zarà Ramen

Via Solferino, 48, 20121 Milano, Italia

+39 02 3679 9000

https://www.facebook.com/zazaramen/

Mi-Ramen Bistro

Viale col di lana, 15 | Viale Col Di Lana, 15, 20136, Milano

+39 339 232 2656

http://mi-ramenbistro.it/

Osaka

Corso Giuseppe Garibaldi 68, 20121 Milano, Italia

+39 02 2906 0678

http://www.milanoosaka.com/

Ryukishin

Via Ariberto 1, 20123 Milano, Italia

+39 02 8940 8866

http://www.ryukishin.it/

Banki Ramen

Via Dei Banchi 14 Rosso, 50123, Firenze, Italia

+39 055 213776

Waraku

Via Prenestina 321/A, 00177 Roma, Italia

+39 06 2170 2358

https://www.facebook.com/Waraku-192626757583758/

Japanese Folklore: The Ring

Ringu: La cassetta maledetta

Photo credits: Movieweb.com

The Ring è il fortunato horror statunitense con protagonista Naomi Watson che nel 2002 infestò i cinema di tutto il mondo. Incassando più di 250 milioni di dollari al botteghino ha ridato vita ad un genere ormai stantio con nuovi spunti per procurare brividi agli spettatori più temerari. Ha avuto anche un sequel, The Ring 2, uscito nel 2005, ed è da poco arrivato sugli schermi The Ring 3 a distanza di quindici anni dalla pellicola originale.

Samara Morgan è una bambina dai lunghi capelli corvini e la pelle nivea, e dalla descrizione potrebbe sembrare una candida Biancaneve. Ma la realtà è ben diversa. Con la sua frase celebre “Tra sette giorni morirai” è un fantasma che conduce alla morte, grazie ad un cerchio senza fine, chiunque veda la sua casetta maledetta.

Samara oggigiorno è tra i “cattivi” per antonomasia del genere Horror americano (come Jason di Venerdì 13, o Freddy Krueger di Nightmare con la sua natura soprannaturale e demoniaca). E diciamolo, è anche una delle possibili maschere di Halloween.

Photo credits: flickr.com

Ma la sua nascita non è americana bensì giapponese, nata dalla penna dello scrittore Koji Suzuki autore dell’omonimo romanzo Ring ( リング Ringu). Suzuki è autore anche di Spiral, uno dei sequel di The Ring, e di Dark Water che si guadagnò un film di cui in America venne prodotto il remake. La protagonista è qui Jennifer Connelly, e anche questo è un Horror di indubbio terrore che però non ha eguagliato la fama di The Ring.

Il remake Americano di The Ring non è molto diverso dal soggetto originale(almeno per i primi film è così). La protagonista è in entrambi una giornalista che ricerca il mistero delle inspiegabili morti dovute alla visione della cassetta maledetta. Purtroppo la donna finirà per portare con sé in questa spirale la propria famiglia in una corsa disperata per salvarsi. Ma il fantasma non è più una inquietante bambina ma una giovane donna.

Sadako 貞子

Photo credits: Movieclips.com

Sadako è il fantasma di una diciannovenne con lunghi capelli corvini che le coprono completamente il volto e che uscendo dal televisore porta il malcapitato ad una violenta morte.

Questo fantasma è in realtà una creatura molto complessa, come tutti i fantasmi Giapponesi, la cui crudeltà non è dettata altro che dalla vendetta. E purtroppo, quando la missione di vendicarsi di chi gli ha fatto male nella loro vita umana si conclude, l’odio ormai ha preso il sopravvento. Ogni possibile redenzione è perduta.

Sadako Yamamura era il suo nome umano e in tutti i film abbiamo una visione della sua storia e sappiamo qualcosa del suo personaggio. Ma è nel prequel della prima saga, The Ringu 0: Birthday, che abbiamo una visione completa della sua vita terrena.

Photo credits: anythinghorror.wordpress.com

Prima di diventare il fantasma senza pace che caratterizza tutto il racconto Sadako nasce da un rapporto proibito. Di padre ignoto, si vocifera fosse un demone, sua madre era una sacerdotessa devota alle arti nere. Sin dall’infanzia viene perseguitata dalle voci secondo cui la vicinanza con lei porti sciagura e morte perché dotata di enormi ma oscuri poteri. Potrebbe avere un lieve spiraglio di luce in una vita tormentata quando ormai adolescente si trasferisce a Tokyo con il professor Ikuma. Ex amante della madre, il professore tratterà la giovane come una figlia che arrivata all’età adulta si iscrive in una compagnia teatrale. Qui, una serie di tragici avvenimenti la porterà a diventare attrice protagonista, ma con questo anche all’ascesa della parte maligna dentro di lei.

Si scoprirà infatti che in lei vivono due entità, la sua parte umana e buona, e la parte demoniaca dall’aspetto di una bambina. E saranno le vessazioni e la morte della sua parte buona, uccisa dai suoi colleghi, che faranno prevalere il lato demoniaco, e scateneranno la serie di fatali avvenimenti conseguenti.

Photo credits: noset.com

Ikuma cercherà di uccidere anche la Sadako malvagia buttandola in un pozzo e sigillandolo, ma l’entità sopravvive alla caduta pur restando imprigionata. Qui il demone diventa sempre più forte concretizzando alla fine il suo odio nella videocassetta maledetta che in sette giorni conduce alla morte chiunque la guardi.

Ma ciò nonostante non si può non nutrire compassione per lei, essere travagliato. Nell’ultimo attimo di umana lucidità, prima che la sua parte demoniaca prenda il sopravvento, ricorda Toyama l’unico ragazzo che abbia mai amato.

I film hanno una sostanziale differenza rispetto al libro di Koji Suzuki per quanto riguarda la storia del personaggio. La giovane ha infatti una vita ben più travagliata e molto più complessa, che si conclude con un destino fatale.

Banchō Sarayashiki 番町皿屋敷

Photo credits: Wikipedia

Il personaggio creato da Koji Suzuki, come molti altri del cinema horror giapponese moderno, prende spunto da una antica leggenda.

Parliamo della storia di Okiku e i nove piatti. Molto spesso anche il teatro Kabuki ne ha preso spunto per le sue rappresentazioni e ve ne sono diverse versioni.

In tutte la protagonista è Okiku, una bella e giovane serva che lavora per la famiglia di Aoyama Tessan un samurai innamorato di lei. Innumerevoli volte la ragazza rifiuta le avance del samurai che per farla cedere alla passione le fa credere di aver perso un piatto di finissima porcellana di un servizio da dieci. Okiku conta e riconta i piatti ma il decimo non salta fuori. La povera piange disperata perché sa che la pena che la attende è severa ma il samurai la rassicura dicendo che in cambio del suo amore non subirà punizioni. Okiku rifiuta è il samurai offuscato da un raptus di rabbia la spinge in un pozzo facendola morire. Okiku torna come fantasma per tormentare il suo assassino continuando senza sosta a contare fino a nove e poi iniziare a piangere. Solo un monaco esorcista riesce a liberare lo spirito durante la sua ennesima apparizione notturna. Dopo averla fatta contare fino a nove il monaco urla DIECI! cosi facendo libera Okiku ora pronta ad andare in paradiso.

Photo credits: Wikipedia

Ci sono, come già detto, diverse varianti di questa leggenda, tutte più o meno simili. In una la storia si svolge al castello Himeji e in alcune Okiku muore per un complotto di corte, in altre perché il suo amante, lo shogun, la uccide per aver rotto volontariamente il decimo piatto.

In ogni versione comunque si è mossi a compassione per questo personaggio, sicuramente oscuro ma allo stesso tempo infelice.

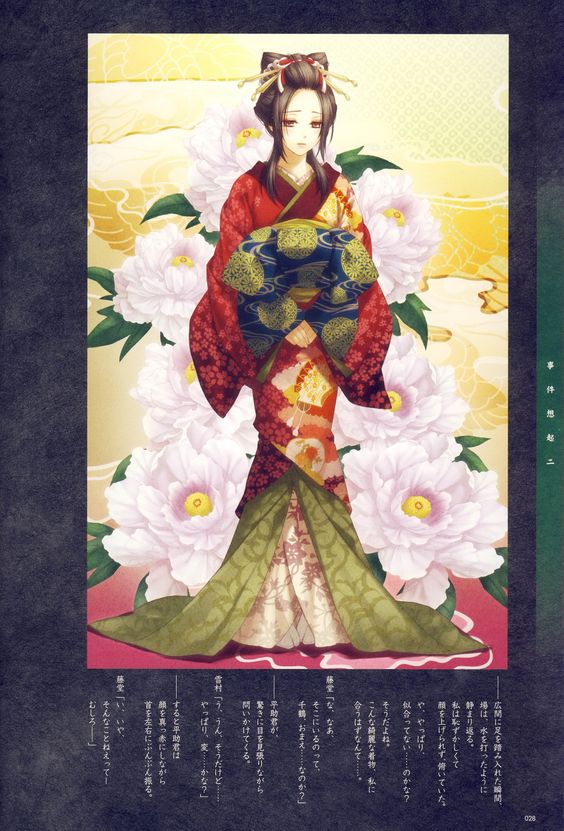

Japanese Tradition: Oiran

Oiran

Cortigiane che dettavano moda.

photo credit: pinterest

Nell’antico Giappone le “donne di piacere” erano le Yūjo (遊女). Questo termine ne indicava il mestiere e marcava la differenza tra le prostitute comuni e le cortigiane ovvero le Oiran (花魁). La figura che vedremmo nel seguente articolo è proprio quella delle Oiran.

Il termine deriva dalla frase ‘oira no tokoro no nēsan’ (おいらの所の姉さん) ovvero “Mia sorella maggiore”. La traduzione del nome potrebbe però anche essere “Il fiore che primeggia” scritto con i kanji: 花 (Hana) “fiore” e 魁(Sakikage) “leader”. Questo temine fu coniato per le prostitute di alto rango del distretto a luci rosse di Yoshiwara (吉原) a Edo, l’odierna Tokyo. Venne usato successivamente per indicare le cortigiane.

photo credit: pinterest

Le Oiran svolsero la loro attività nel periodo Edo, nei Yūkaku quartieri del piacere (da non confondere con le Hanamachi dove vivevano solo le Geisha). Questi quartieri venivano costruiti fuori dal centro città di Kyoto, Osaka e Edo, unici luoghi dove la prostituzione non era illegale. Al contrario delle Yūjo che vendevano i propri favori sessuali, le Oiran intrattenevano il cliente non solo con il corpo ma anche con le loro abilità. Queste comprendevano il Sadō o cerimonia del Tè, l’Ikebana, l’arte dei fiori, suonare vari strumenti, leggere e avere un’ottima cultura generale. Infatti dovevano essere in grado di intrattenere il cliente anche sostenendo con lui una brillante conversazione. Il rango più alto era costituito dalle Tayū (太夫) le quali potevano avere il privilegio di rifiutare i clienti. Seguivano le Kōshi (格子). I loro clienti erano parte dell’élite della società, come daimyō e ricchi feudatari, poiché la loro parcella era molto dispendiosa. Basti pensare che solo una notte con una Oiran equivaleva al salario annuale di un lavoratore. Per avere un incontro bisognava essere inviati dalle stesse per poi entrare in liste d’attesa di settimane.

L’ultima Oiran ufficiale visse fino 1761. C’è da notare che con la fama crescente delle Geisha man mano diminuivano le richieste per le Oiran. Oggigiorno non viene più svolta questa professione nel senso vero della parola ma ha la finalità di far rivivere le tradizioni del Paese, i vecchi usi e costumi.

La cosa affascinante di queste figure era che per via dell’isolamento dovuto alla legge sulla prostituzione (erano relegate in zone periferiche) vennero idolatrate e mistificate. In più dettavano mode e costumi. Erano loro che portavano le acconciature più particolari e i kimono più estrosi e ricchi, con Geta (sandali Giapponesi) alti quindici centimetri.

photo credit: tokyocheapo.com

Shinano, Sakura e Bunsui.

Esistono diversi eventi durante l’anno che celebrano queste donne.

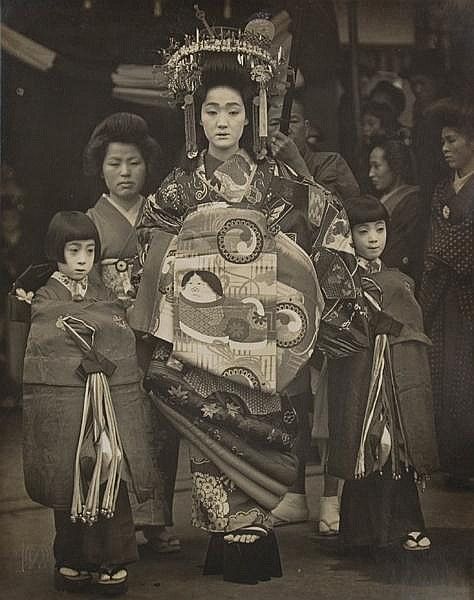

Il primo di questi si svolge in aprile a Tsubame nella regione di Hokuriku ed è il Bunsui Sakura Matsuri Oiran Dōchū. Si tratta di una parata famosa in tutto il Giappone dove ragazze di ogni regione si sfidano per avere il ruolo delle tre Oiran protagoniste: Shinano, Sakura e Bunsui. I nomi derivano dai fiori che nascono da tre specie diverse di ciliegi. Le ragazze sfilano davanti ad un corteo di minimo di settanta figuranti diversi tra Kamuro le loro aiutanti, servi e concubine. Ogni figurante viene selezionato ogni anno con la più massima accortezza.

photo credit: wikipedia

A settembre la parata Oiran Dōchū percorre Shinagawa, ed a inizio ottobre a Nagoya, intorno al tempio Ōsu Kannon, c’è lo Ōsu Street Performers Festival dove migliaia di spettatori assistono a due giorni di parata. Qui le Oiran sfilano nelle gallerie dei negozi dell’Ōsu Kannon district con tutto il loro entourage. Esso è composto dagli Yojimbo simili ai Samurai ma che hanno il ruolo di bodyguard, e dalle apprendiste.

Affascinanti, sensuali e misteriose come tutto in Giappone, donne dai mille volti e dai mille talenti, bellezze di un tempo passato.

Japan Italy Bridge Tips: Edogawa Fireworks

Edogawa Fireworks

photo credit: ajpscs

Se questa estate vi trovate a Tokyo vogliamo consigliarvi un meraviglioso spettacolo che da 43 anni a questa parte allieta gli abitanti di Edogawa (quartiere speciale di Tokyo che prende nome dal fiume Edo).

L’Edogawa Fireworks Festival si svolge ogni primo sabato d’agosto, dove per 75 minuti non potrete far altro che tenere gli occhi puntati al cielo. Uno spettacolo con più di 14,000 fuochi d’artificio lanciati nei cieli di Tokyo.

Vi consigliamo di assistere al festival dal Parco di Shinozaki, a circa 15 minuti a piedi dalla stazione omonima di Shinozaki. Guardare ovviamente è gratuito ma fatte presto a prendere il vostro posto perfetto! Giusto in tempo per rimanere estasiati dalla spettacolare apertura con il lancio di 1,000 fuochi d’artificio d’argento e oro solo nei primi incredibili minuti.

Se non siete sicuri di riuscire a conquistare il vostro posto in tempo potrete riservarne uno acquistando il vostro biglietto qui (Solo Giapponese).

Che siate da soli, o in dolce compagnia, con gli amici o con la vostra famiglia.. Non perdetevi questo spettacolo unico!!

DATA: 5 Ago, 2017

ORARIO DI INIZIO/FINE: 19:15 – 20:30

LOCATION: Edogawa Fireworks Festival Location

INGRESSO: Libero / Posto riservabile aquistando tramite questo sito (Solo giapponese)

STAZIONE PIÚ VICINA: Shinozaki

DOVE: Ichikawa, Tokyo

photo credit: cate♪

photo credit: Luke Kaneko

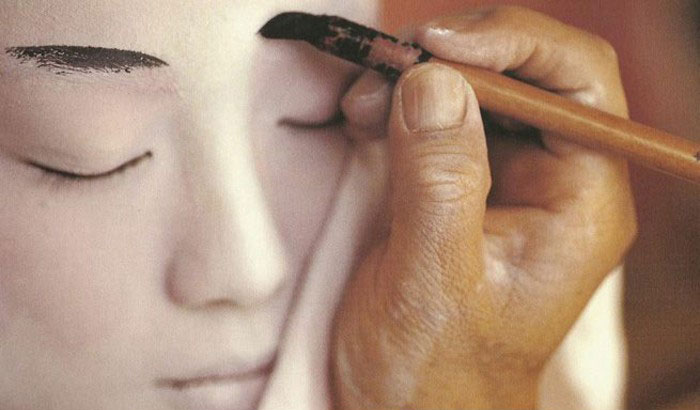

Japanese Culture: Geisha & Maiko

Maiko e Geisha: Artiste danzanti.

photo credit: metmuseum.org

La figura artistica più rappresentativa ma al contempo misteriosa del “Sol levante” è la Geisha (芸者 “Persona d’arte”).

Spesso viene confusa con la Maiko (舞妓 “Fanciulla danzante”) che è l’apprendista a questa professione. Per diventare una Geisha si deve fare una lunga gavetta e frequentare scuole apposite. Qui si impara a danzare, cantare e nell’uso del Shamisen (三味線 “Tre corde” tipico strumento musicale). Per quanto riguarda l’intrattenimento con il pubblico, la Maiko impara tutto accompagnando una Geisha in giro per le case da tè. Il rapporto che c’è tra Maiko e Geisha è una “sorellanza” vera e propria. Le due si chiameranno rispettivamente imoto-san "sorella minore" e onee-san “sorella maggiore". Il legame è cosi stretto che il nome d’arte per la futura Geisha viene deciso dalla “sorella maggiore” e lo porterà per tutta la carriera artistica.

photo credit: freshdesignpedia.com

I kimono dai colori sgargianti col passare del tempo tenderanno a diventare scuri. Le Nihongami, pettinature risalenti al periodo Edo, sono molto complicate sia da fare che da mantenere. Esse vengono ornate dai Kanzashi, spilloni decorativi che variano a seconda delle stagioni (Es. fiori durante la primavera, colombe a capodanno). Queste diventeranno più sobrie ed il trucco eccessivo con piccole labbra color carminio che risaltano su una maschera nivea sarà sostituito per un risultato più naturale. Il piccolo vezzo del collo esposto (che nella cultura giapponese è una delle parti più sensuali della donna) da due linee bianche dipinte passeranno a tre.

Nel passato le figlie delle Geisha percorrevano fin dalla prima età questo percorso. Oggi è più comune iniziare l’apprendistato conclusi gli studi universitari. Tuttavia, questa è una professione che si sceglie liberalmente e non per continuare una tradizione familiare. C’è da dire che questa comunità tutta al femminile con tradizioni rigide e una forte etica morale tiene molto a celare il loro segreto secolare.

“L’arte di essere donna”

photo credit: Pinterest

Solitamente, nel nostro immaginario vediamo la Geisha come donna ricca di fascino ma succube, devota al proprio uomo in ogni più piccolo capriccio. Tuttavia questo è un errore poiché nel passato furono le prime donne con piena autonomia della società Nipponica.

Tutto iniziò con i Taikomochi (太鼓持), giullari che intrattenevano con acrobazie e battute umoristiche lo Shōgun (将軍 "comandante dell'esercito") e i Daimyō (大名) la nobiltà feudale.

Benché i Taikomochi erano molto amati per lo spirito goliardico che portavano a corte, questa figura andò man mano sparendo con l’apparizione delle prime Geisha ovviamente dando non poco scalpore ma venendo preferite per i movimenti sensuali e la grazia femminile.

Ma queste donne non erano cortigiane ne prostitute di lusso. Queste ultime nella cultura giapponese sono identificate come Oiran (花魁). Le Geisha erano artiste molto richieste. Le loro specialità includevano danza, canto e musica. Dovevano inoltre essere buone conversatrici e intrattenitrici. Esse esercitavano questa professione nel Okiya (置屋) "case delle geisha" a Kyoto la allora capitale dell’impero.

Durante la seconda metà dell’Ottocento l’isolamento del Giappone durato circa duecento anni terminò. Questo fu il momento in cui l’Europa conobbe un porto nuovo ed esotico.

Assieme a questo, tutto il resto del mondo conobbe anche la figura della Geisha ed il suo fascino. Questo influenzò anche la moda e costume occidentale. Puccini musicò la struggente Madama Butterfly e nell’arte furono muse per i più grandi pittori del tempo. Manet, Monet, Klimt, Renoir e Van Gogh sono solo alcuni dei pittori che hanno provato ad ispirarsi al Giapponismo. Questo è un movimento artistico che offre tributo all’arte Ukiyo-e (浮世絵 "immagine del mondo fluttuante"). Ma non solo, anche alle stampe dei grandi maestri Katsushika Hokusai (La grande onda di Kanagawa) e Kitagawa Utamaro. Quest’ultimo è famoso per le bellissime stampe dedicate alle donne. Più questo movimento artistico prendeva in patria, più le stampe ukiyo-e diventavano famose e richieste in occidente.

photo credit: makeuppix.com

“Mogli del crepuscolo”

Durante la Seconda Guerra mondiale con l’approdo degli Americani la figura della Geisha venne distorta. Ad essa fu attribuito un ruolo da prostituta poiché le giovani che davano conforto ai soldati erano chiamate “Geisha Girls”. Questo causò un’idea anti-femminista e sbagliata di queste donne.

Per le regole rigide di questo lavoro difficilmente la Geisha nel passato poteva concedersi l’amore. Poteva avere come compagno solo il suo Danna (旦那). In giapponese vuol dire padrone ma era più simile ad un marito che la Geisha poteva concedersi. Egli si prendeva cura della sua protetta finanziando le sue esibizioni e talvolta cancellando il debito che la giovane aveva con l’okiya per le spese scolastiche. Era quasi sempre il Danna che sceglieva la sua Geisha non il contrario. Nonostante questo, a lungo andare non era insolito che tra i due nascesse l’amore.

Ma per fortuna i tempi sono cambiati. Oggi le Geisha possono amare liberalmente, ma ovviamente concludendo l’attività con il matrimonio. È consuetudine che le ex Geisha diventino insegnanti di danza.

still dal film "Memorie di una Geisha"

Il numero delle Geisha è in netta diminuzione ed è un lavoro per lo più fine al turismo. Infatti, il loro pubblico oggi non solo è maschile ma anche femminile.

Ricordiamo le meravigliose parole di Arthur Golden che con il suo Best Seller “Memorie di una Geisha” ha creato un meraviglioso quadro. Questo ha permesso di riscoprire questo universo parallelo in bilico nel tempo tra passato e modernità.

“La Geisha è un'artista del mondo che fluttua: canta, danza, vi intrattiene; tutto quello che volete. Il resto è ombra, il resto è segreto.”

Japanese Folklore: Kappa

Kappa ovvero “Il figlio del fiume”

Il Kappa è una simpatica chimera, non si sa bene quale sia il suo aspetto, a tratti umanoide, dalle fattezze magari scimmiesche. Il più delle volte però ha il volto di una tartaruga con un becco giallo. Dalle tartarughe ha preso in prestito anche il guscio e una pelle squamosa dai colori acquatici ma in prevalenza di un bel verde alga. Sulla testa porta una foglia di loto contenete dell’acqua ed è da questa che trae i suoi poteri. Lui è il Kappa (河童) o se volete chiamarlo Kawatarō ( "ragazzo di fiume") o Kawako ("figlio del fiume"), ne sarà felice.

Nato come monito per spaventare i bambini dai pericoli che le acque profonde nascondono, è uno Suijin (水神 "dei acquatici") dello shintoismo. Comunemente però la sua figura è uno dei tanti Yōkai (demoni o fantasmi) del folklore Nipponico.

Per quanto il suo aspetto grottesco può suscitare una certa ironia, non è un tipo con cui scherzare perché è un essere dispettoso e malizioso. Nell’antichità si diceva rapisse i bambini perché ne era ghiotto ma non disdegnava nemmeno le viscere di umano adulto. E’ sempre pronto a fare scherzi di cattivo gusto come alzare le gonne dei kimono delle giovani donne al rubare il raccolto dei contadini.

Anche se dispettoso e magari pericoloso, un buon modo per salvarsi da lui sono le formalità. Ebbene sì, è molto educato anche se pare difficile da credere. Ama le buone maniere e se gli farete fare un profondo inchino verserà la sua acqua magica e lui perderà le energie. È anche un essere pronto a mantenere la parola data e a elargire ricompense.

Se ne trovate uno in difficoltà aiutatelo e versate acqua sulla sua foglia, sarà vostro debitore a vita! Magari volete averlo come amico? Beh, Io non vi ho detto nulla ma i Kappa amano i Cetrioli! Ebbene sì! Offrite ad un Kappa queste fresche verdure e vi donerà la sua amicizia, e chi non vorrebbe un Kappa come amico ai nostri giorni?

Il Kappa vive nei laghi o negli stagni profondi e per questo è un ottimo nuotatore. Ma qui c’è proprio da dire: “kappa no kawa nagare”, "un kappa che si fa portar via dalla corrente" , perché anche i più bravi sbagliano, non demordiamo quindi!

Oggigiorno i Kappa sono meno spaventosi, per certi versi più “Kawaii”e innumerevoli anime ne hanno preso spunto. In “Marmalade boy” i due protagonisti Miki e Yu hanno un Kappa di Pelushe come mascotte; diversi Pokemon sono ispirati a questa figura e “Kappa no Coo to Natsuyasumi” ( Un’estate con coo) parla dell’amicizia tra un bambino dei giorni nostri ed un Kappa alla ricerca di suoi simili.

Anche J.K. Rowling ha parlato di queste creature mitologiche nel suo libro “Animali fantastici: dove trovarli”. E se siete interessati a trovare un vero Kappa, o quanto meno ciò che ne rimane, vorrete recarvi ad Asakusa distretto di Tokyo. All’interno del tempio buddista Sogen-ji se ne possono venerare i resti.

photo credit: manganews, wikipedia, facebook.com/TeaFoxIllustrations