Introduction to Japanese poetry

Italy, France, England, America and many other countries in the world offer a vast poetic production, but what is Japanese poetry like? Here we are on this fascinating literary journey to discover something more about the Land of the Rising Sun!

photo credits: grangerprints.printstoreonline.com

Introduction to Japanese poetry

Author: Sara | Inspiration: Tokyo Weekender

Japanese Poetry: Kanishi

photo credits: wikimedia.org

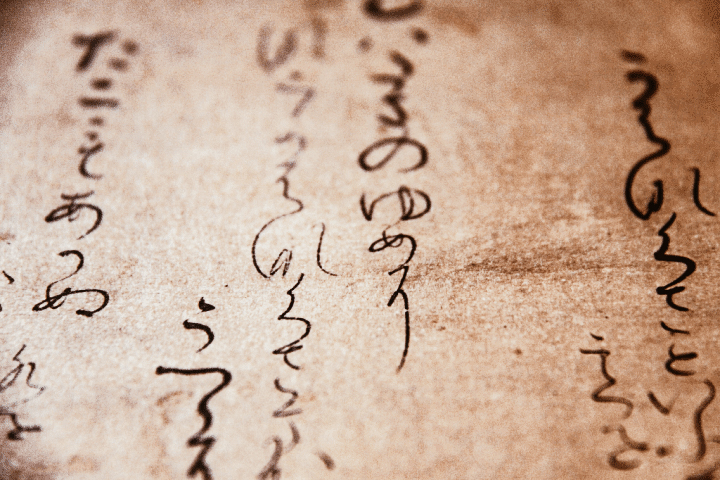

Curiously, most of the literary works of Japanese poetry were born during the Tang Dynasty, from the encounter of Japanese poets with Chinese ones. And so, under Chinese influence, Kanshi 漢詩 became the most popular form of poetry during the early Heian period among Japanese aristocrats and became increasingly popular in the modern period, especially among academics and intellectuals. The themes were free, while the forms were more rigid: the classical ones counted about 5 or 7 syllables in 4 or 8 lines, following the rules of Lushi 律詩 (rhyme on even lines with a regulated tone) and jueju 絕句 (rhyme in even lines and composed only of quatrains) based mainly on the tone of Mandarin Chinese.

The major exponents of this style are certainly Kukai, Sugawara no Michizane, Maresuke Nogi and Natsume Soseki.

Waka

photo credits: https://matcha-jp.com/jp/289

Unlike Kanshi, Waka 和歌 was classical poetry written in Japanese with two very precise forms: Choka, 長歌, or long poems with no length restrictions. The structure is simple and consists of 2 lines of 5 or 7 syllabic sounds (which determine the accent) that ends with 3 lines of 5, 7 and again 7 syllabic sounds. Tanka, 短歌, instead has a similar structure, but they are shorter poems, often consisting of only five groups of words respectively of 5, 7, 5, 7 and, finally, 7 syllabic sounds. Waka does not follow the rhyming rules and is still very popular in modern Japan, even if now the Tanka form is preferred: the more incisive brevity reflects as always the essentiality of deep culture. The poet par excellence is certainly Machi Tawara.

Haiku

photo credits: wikimedia.org

What is the Japanese poetic composition that we consider among the most famous? Without a shadow of a doubt, it's the Haiku, 俳句. Loved by all, it is usually composed of 3 verses and 17 total syllabic sounds, schematically 5/7/5. Haiku experienced its development in the Edo period when many poets relied on this genre to describe nature and human events directly related to it. In fact, these small "compositions of the soul" express the beauty of every single instant, representing "the moment" and giving the reader that sense of "enlightenment" thanks to the images that the words evoke. The most famous and beloved poets are undoubtedly Basho, Yosa Buson, Kobayashi Issa, and Masaoka Shiki.

Our journey into Japanese poetry ends here, for now. This is a very short overview that has allowed us to enter the world of literature of our beloved Japan. What is your favourite form of poetry among the above? Mine is easy to guess: I particularly love Haiku. Here is one of my favourites by Matsuo Basho:

Let's take

the marshy path

to get to the clouds.

Continue to follow us to discover other little pearls of this oriental world and I recommend that you continue on the path you have taken: happiness is always in front of you!

Genji's Tale

Murasaki Shikibu is the name behind the Japanese woman who wrote what is called the world's first novel, The Genji monogatari (源氏物語 lett. "The Genji Tale").

Genji's Tale, The World's First Novel

Author: SaiKaiAngel | Source: Tokyo Weekender

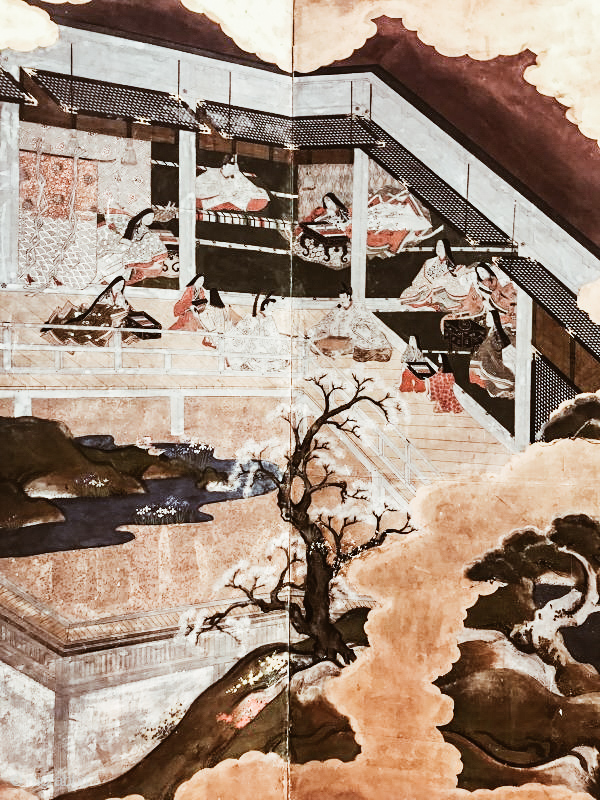

photo credits: tokyoweekender.com

Every work of contemporary art is the result of centuries of cultural history. In the case of Japanese literature, we are talking about 1,000 years of written prose and poetry. It all began in the Heian period (794-1185) with Murasaki Shikibu, a companion and member of a minor branch of the powerful Fujiwara clan. Murasaki was the author of one of the most important literary works in the world, The Tale of Genji, published in the early 11th century. By way of comparison, it is thought that the first novel in modern European history is Cervantes' Don Quixote, first published in 1605.

Heian aristocracy

While Shikibu was undoubtedly a pioneer of fiction in Japan, not much is known about her, not even her first name. At that time, the maiden names of elite women were not registered. The name Murasaki Shikibu would have been created based on one of the characters in The Tale of Genji and on his father's status (Shikibu, which means "Ministry of Ceremonies" in Japanese), although historians still dispute this theory.

Like many women of her status, she lived relatively comfortably, although the aristocratic lifestyle had some restrictions. The elite of the Heian period favoured high education and culture, and often the most powerful individuals were also the most educated.

Men learned everything from poetry and languages to law and politics. Women, on the other hand, were limited to the arts because this was what was considered attractive at the time. Chinese was an important language to know for those directly involved with the court and to participate in literary circles, but women usually could not study it.

photo credits: wikipedia.org

This has not prevented aristocratic women from investing in the creative field, using hiragana and contributing significantly to the genre of the poetic diary. Lady Murasaki's Diary together with Sei Shonagon's The Pillow Book are the main representatives of the genre to date.

Through fragments of Shikibu's diary and narrative work, historians have been able to learn about the unique aristocracy of classical Japan. At the time, poetry and prose were written based on the lives of their authors, but Shikibu's was distinct from the masses in that it was clearly a work of fiction - although many claim that the stories in The Tale of Genji were inspired by real events.

Genji's Tale

Genji's Tale is thought to be the world's first written work of fiction. It’s not certain whether Shikibu wrote the complex story in a couple of years or decades, but what is certain is that this complete literary work is a portrait of the Heian aristocracy in all its complicated hierarchies.

What is even more impressive is that, despite the long list of characters and appearances throughout the book, the story still surrounds only what at the time was less than 1% of the population, the highest elite.

Reading the chapters gives you a vivid idea of what it was like to be a man or a woman in the Heian period, with the corresponding expectations. The protagonist, Genji, is the archetype of a hero of the period, the perfect man. Son of an ancient emperor, his right to the throne was taken away from him and he was demoted to populan when he changed his name to Morimoto.

The Story of Genji Monogatari

The work tells of one of the sons of the Japanese emperor of the Heian era, known by the name of Genji or rather Hikaru Genji (Genji Splendente). Genji, however, is just a different way to read the kanji of the Minamoto clan (the reading On of Minamoto is in fact 源 Gen, the same kanji present in the word Genji), a family that really existed and to which the author wanted to allude. Born from the emperor's relationship with one of his concubines, and therefore unable to be part of the main branch of the imperial family or aspire to the throne, Genji is adopted by the court which allows him to climb the high ranks starting from the position of simple court official.

The whole story then revolves around Genji's love life and his various relationships, thus showing the customs of the court society of the time. Despite his numerous relationships and the different wives he will have during his life, as a libertine Genji still shows his particular loyalty and bond with all the women in his life by not abandoning any of his wives or concubines, especially at a time when for a concubine or wife to be left by her protector meant abandonment of society and marginalization.

Among them, however, one woman was a particular presence in the life of the young Genji: Fujitsubo. The premature death of his mother left in Genji a void that the young man tried to fill throughout his life, always looking for a mother figure in all the women with whom the young man fell in love. He thought he would find the mother figure in Fujitsubo, a concubine of the Emperor, his father.

In the woman, Genji saw not only the sweetness of the mother but also beauty and gentleness, and although he was reciprocated by the woman, the two were forced to repress their feelings because she "belonged", as concubine and then bride, to the Emperor, and Genji had recently joined the Emperor in marriage with Princess Aoi.

The story continued telling the intertwined stories of all the characters whose lives were intertwined and united until the end of the novel, with the conclusion that saw Genji in old age, reflecting in solitude on the meaning of life and the transience of things and their fleeting beauty. However, there are other chapters, known as Uji's Chapters, which, like the rest of the work, continue to recount events even after Genji's death and have as their protagonists Genji's son and a friend struggling with their love affairs.

However, the story ends abruptly, almost in the middle, leaving the various foreign scholars and authors who have translated the English version to imagine that the work has not been completed by the author. In fact, it seems that Murasaki didn't plan any end for the novel but simply continued to write it as long as he wanted or could leave it incomplete.

Structure of the Genji Monogatari

photo credits: rugrabbit.com

The story that tells the life of Prince Genji, tells about the young prince's youth, his rise to success, his worldliness and loves until his fall and then rise again. A plot in which there are bewitching and beautiful female figures as a frame. As for the language, it is very complex and not easy for modern readers: being from the Heian period and moreover in a court environment, Murasaki's language has a very complex grammar.

Each character is almost never called by name but by their honorary title or according to their class. For women, instead, typical colour of their clothing is indicated, different for each female character, or alludes to a woman using the rank of a male relative of the first order to which she belongs.

Another difficulty of the novel is the presence of poetry and conversations written in verse. This often served the characters to communicate subtle and veiled allusions in a court environment: poetry is classic Tanka poetry. Like most writings of the Heian period, the Genji was most likely written all, or almost all, in kana, and not using Chinese characters as it is written by a woman for a female audience.

It is well known that in the Heian era writing in Chinese characters was something purely masculine, but women were forbidden.

Besides many suggestions of a society dominated by men, the novel was proof of something that could be even more crucial: women had undeniably played a great role in the propagation of the arts. In fact, while the Heian period saw many failed attempts to revolutionize Japanese government policies, what's left is a rich attachment to the culture that Japanese society still clings to today.

The prose and poems written in hiragana by the women of the court ensured that the lower classes could also enjoy them. In other words, the Heian period is seen as a time when the art world in Japan was born. Not only Shibiku is an important historical figure for its legacy in Eastern and international literature, but she is a symbol of an era in Japan when women were successful in ways never seen before.

Murasaki Shikibu in popular culture

Shikibu is one of the most significant historical figures in East Asian cultural history and, over the next millennia, has remained a staple in Japanese high schools and colleges, just like Shakespeare in Europe and North America.

There have been many important translations and interpretations, as well as a fair amount of criticism. In Japan, Genji's tale is commemorated on the rare 2,000 yen note and Murasaki Shikibu is the name of the Japanese berry plant.

Like the story of the 47 ronin, Genji's Tale has been adapted for the big screen several times, and the latest is the feature film Genji monogatari: Sennen no nazo (2011). In recent years, Murasaki Shikibu herself has appeared in mobile games such as Fate/Grand Order and Monster Strike, where the characters are inspired by her work.

Japan History: Eugène Collache

Eugène Collache (29 January 1847 Perpignan - 25 October 1883 Paris) was an officer in the French Navy of the 19th century. He left the Minerva ship in the port of Yokohama with Henri Nicol to rally other French officers, led by Jules Brunet, who had embraced the Bakufu cause in the Boshin war. On November 29, 1868, Eugène Collache and Nicol left Yokohama aboard a commercial ship, the Sophie-Hélène, chartered by a Swiss businessman.

Eugène Collache, between France and Japan

Author: SaiKaiAngel

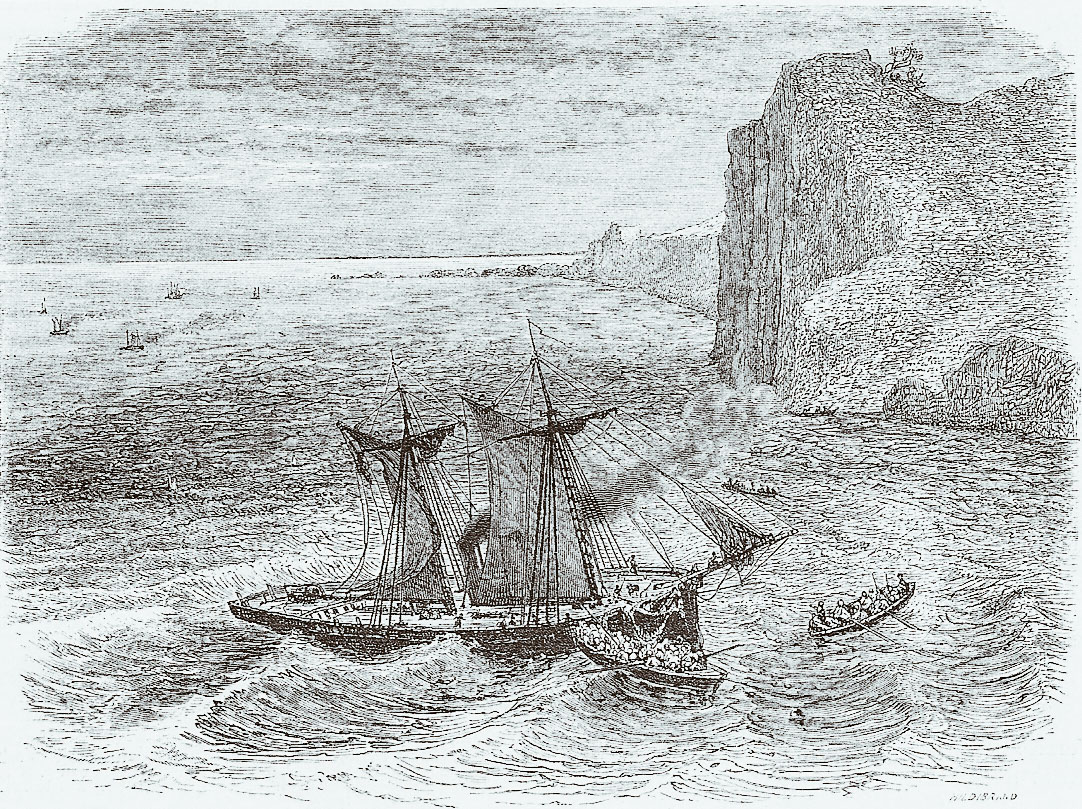

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Eugène Collache and Boshin's war in Japan

Eugène Collache and Henri Nicol first reached Samenoura bay in Nanbu province (modern Miyagi prefecture), when imperial forces had subdued the daimyō of Northern Japan and that those in favour of the shōgun had fled to the island of Hokkaidō. In Aomori, they were warmly welcomed by Tsugaru's daimyō. An American ship warned them of an arrest warrant against them and Eugène Collache, always with his friend Henri Nicol, decided to board that American ship to reach Hokkaidō.

During the winter of 1868-1869, Eugène Collache was commissioned to establish fortifications in the volcanic mountain range to protect Hakodate.

The surprise attack on the Imperial Navy, in which Collache participated in the battle of Miyako, occurred on May 18. Collache was on the ship Takao, while the other two ships were the Kaiten and the Banryū. The ships encountered bad weather, so the Takao reported engine problems and the Banryu returned to Hokkaido, without joining the battle.

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Kaiten instead planned to enter the port of Miyako with an American flag. Due to engine problems, Takao was sailing after him and at that moment Kaiten joined the battle for the first time by raising the Bakufu flag a few seconds before boarding the imperial warship Kōtetsu. The Kōtetsu managed to repel the attack with a Gatling gun and the Kaiten came out of Miyako bay just as Takao entered it. Eventually, Kaiten fled to Hokkaidō, but Takao was unable to leave the pursuers and was destroyed

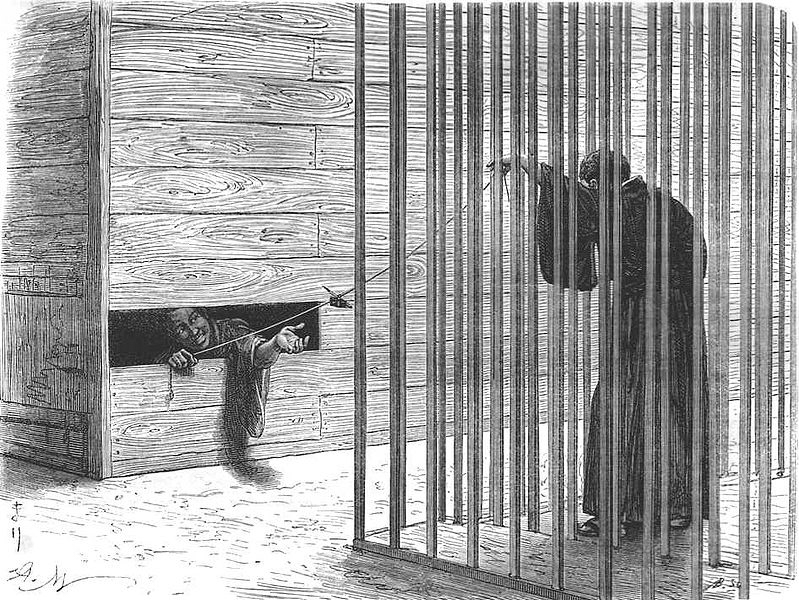

At that point, Collache tried to escape with the favor of the mountain, but surrendered after a few days together with his troops to the Japanese authorities. They were taken to Edo for arrest. Collache was judged and sentenced to death, but eventually pardoned and transferred to Yokohama aboard the French Navy frigate Coëtlogon, where he joined the French rebel officers led by Jules Brunet.

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Return to France

Returning to France, he was discharged from the military and called a deserter, but the sentence was light and he was allowed to return to the list for the Franco-Prussian war together with his friend Nicol.

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Books

The experience in Japan was very important, so Eugène Collache wrote "An Adventure in Japan 1868-1869" ("Une aventure au Japon 1868-1869"), which was published in 1874.

The shōchū and its infinite pairings

If you follow us closely, you've surely heard about shōchū several times. I’m about to make a small recap just to remind you what we are talking about: shōchū is a distillate made from barley, sweet potatoes or rice. Generally, it contains 25% alcohol so it is lighter than vodka but stronger than wine. The production area of this distillate is the island of Kyūshū, but today it’s produced practically everywhere in Japan.

The shōchū and its infinite pairings

Author: SaiKaiAngel

photo credits: japantimes.co.jp

The pandemic caused by COVID-19 has caused or even just resurrected many fears in the minds of many, from the fear of dying to the much lighter fear of gaining weight.

We are all, even more, looking for everything that can be healthy... well, it seems that shōchū may be just one of the things we should be looking for. Shōchū expert Stephen Lyman, the author of the book "The Complete Guide to Japanese Drinks" also nominated for a James Beard Award, has replaced beer and wine with shōchū and thanks to this he has lost seven kilos in seven months! Obviously, if we give importance to weight loss, it is absolutely not for an aesthetic issue, but to avoid serious diseases such as obesity.

The shōchū in 2003 has reached a sales volume even higher than the sales of sake! Its popularity is growing, driven also by its alleged medical benefits - ranging from the prevention of blood clots to the containment of obesity - which make it a healthy alternative to other alcoholic beverages.

photo credits: japantimes.co.jp

Lyman, a native of New York, discovered this beverage in an izakaya bar in Manhattan more than 12 years ago and it was love at first sight. Lyman explains: "I've always loved wine and craft beer. Distilled drinks were a bit too strong for me and I was always looking for a drink that would have been perfect with food".

Shōchū is good for diet too

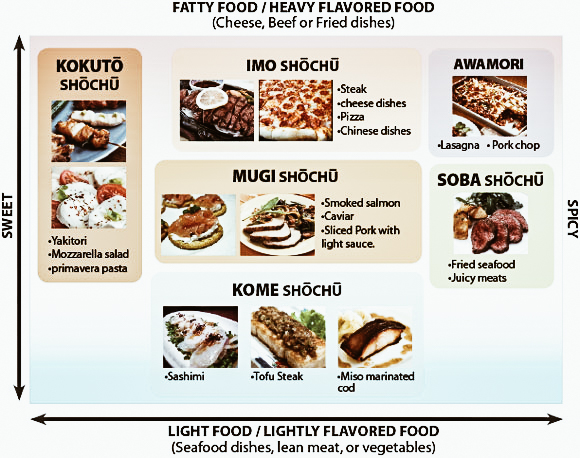

In 2011 Lyman's interest in shōchū became a real passion, and he started drinking it, even more, when a sports injury caused him a gain of weight. "I knew that shōchū was low-calorie, so I decided to give up wine and beer for shōchū six days per week," he says. Within a month, Lyman lost two kilos; after two months, five. Because of this, having found the shōchū could make him lose weight without altering his lifestyle, he began to take an interest in this Japanese drink and all possible pairings. Lyman says that the pairing of shōchū is possible with more than 50 possible ingredients! Richer shōchū notes work with heavier foods and, in particular, with miso dishes.

The barley shōchū obtained by vacuum distillation with a lighter and more aromatic style is perfect with white fish dishes, delicately flavoured sashimi and simmered. In general, the sweet-potato shōchū instead goes well with meat such as pork, while the kokutō (black sugar) shōchū, which is similar to rum, harmonizes with grilled meat. The full taste of shōchū is a surprising accompaniment to dark chocolate.

Also, the Iichiko Silhouette also called "the Johnnie Walker of shōchū" tastes like stone fruit and paired with soda water can be served with watermelon and mint soup. The shōchū Yamatozakura resists the sweet and earthy spices of Taiwanese braised pork with aniseed and cinnamon, while the Komaki Issho Bronze, a shōchū of sweet potatoes easy to eat, goes perfectly with a vegan stew of sweet potatoes, chickpeas and peanuts.

photo credits: mtcsake.com

But let's go more specifically and analyze some of the tastiest combinations:

Imo, sweet potato shōchū

Pork chops, pizza Margherita, fried tempura

Imo has a sweet aroma and taste, which goes well with substantial dishes or fried foods. It also is good with rich Chinese food or pizza with lots of cheese.

Mugi, derived from barley

Smoked salmon, caviar, sliced pork with lemon sauce

The mugi has a very clean and fresh taste. Technically this drink goes well with any kind of food, but it tastes better with a simple dish than with an oily dish. The aroma of barley enhances the vegetable sauce.

Kome, from rice

Sashimi, trout marinated in miso, tofu steak.

The kome has an umami (flavor) that goes well with any kind of food but particularly indicated with the delicacy of sashimi. It can also be enjoyed with rice dishes.

Kokuto, sugar cane shōchū

Yakitori (grilled chicken), pasta primavera, mozzarella salad

The Kokuto is made with sugar cane and can taste a bit fruity. The fragrance of kokuto is similar to the one of sweet syrup, but the taste is very simple and delicate and not extremely sweet. This particular taste can bring out the original flavours of the food and is indicated with soy sauce dishes that have a slight sweetness.

Awamori shōchū

Porkchop, lasagna, banana pancake

Awamori has a special aroma and rich flavour that goes well with spicy or heavy foods such as cheese and creamy dish.

Soba shōchū

Penne arrabbiata, fried oysters, meatballs

The characteristics of soba are very mild and clear-cut but at the same time a little bit bitter. This can be enjoyed with slightly spicy foods or juicy meats.

I'm sure that as soon as you've finished reading this article you're already looking for the perfect shōchū for you, are you ready for a completely new adventure and completely different lunches and dinners?

Chadō, the Japanese Tea Ceremony

If there is anything in which the Japanese are true masters is in living in harmony with life itself, this is demonstrated by the Japanese tea ceremony, also known as Chadō. A real gift, their innate ability to flow naturally with everything that happens from the smallest everyday gestures. Rooted in the here and now, fully in tune with the present moment.

Chadō, the Japanese Tea Ceremony - 茶道

Guest Author: Flavia

photo credits: YouTube

Therefore, it's not surprising that the people of the Rising Sun have been able to translate this extraordinary talent into various forms of art. They are in fact real ways of living (the so-called Ways - 道, Dō) through which to express their ability to grasp the meaning of existence. The Chadō or Sadō ( 茶道 ), or the Way of Tea, is one of the most significant and appreciated. Otherwise called Cha no Yu (茶の湯) - literally "Hot water for tea" - it is a social ritual aimed at educating the individual. A true philosophy of life and aesthetic form that has strongly permeated Japanese culture. But how did this tradition originate?

The matcha, from southern China in the bosom of Zen

Originally from the Yunnan region, the tea plant has been known for its therapeutic properties since ancient times. Initially, it was in fact used as natural medicine, it will only become a form of "delight" later. It was consumed in a monastic environment, being used by monks to promote concentration during meditation or studies. However, it will land in Japan at the beginning of the Heian period at the hands of Japanese monks who went to China to study Zen (禅, from Chinese chan).

Tradition attributes in particular to the monk Myōan Eisai - who lived between the 12th and 13th centuries - the role of the precursor of the tea ceremony. As it happened, he introduced in Japan the form of Rinzai Zen Buddhism (Linzhi or Linji, in Chinese) and with it a specific method of preserving and preparing tea. In essence, it provides that tea is kept away from light and oxygen and prepared according to the method of suspension (instead of infusion): this allows to better preserve its properties. The tea associated with the ceremony will become known as Matcha (抹茶), that is powdered tea. Actually, from that moment the consumption of tea will begin to spread on a large scale, leaving the monastic and aristocratic circles where it had been confined until then.

photo credits: tesoridoriente.net

Therefore Tea (Cha, 茶) has its roots in the Zen doctrine, which will remain decisive also for the diffusion of Chadō, inexorably permeating it. Zen and theism, therefore, developed at the same pace (since the 12th century). A key role here will be played by the equally nascent Samurai class destined to dominate the scene shortly afterwards. The caste will welcome the Zen doctrine, which will make it totally its own, and the cult of tea as a sort of status symbol.

Rikyū, father of Cha no Yu

After Eisai, other masters will leave their mark on the Chadō still in "embryonic" form. This is Murata Jukō, father of the Wabi-cha style ( 侘茶 ) - already well distinctive of the Japanese style compared to the Chinese one - and Takeno Jō. However, at this stage it cannot yet be configured as a real ceremonial rite. It will be necessary to wait until the sixteenth century for a real codification to take place and transform it into the form that has reached our days.

Creator of this reform, none other than the historic tea master of Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Sen no Rikyū, whose imprint will be revolutionary. He will go further than Murata Jukō, completely undermining the aesthetic taste of the Shōgun. Before his intervention, in fact, the execution took place focusing on the objects, that is, thought of their performance. With Rikyū, the focus becomes the people and the ceremony becomes less elaborate and more essential. In addition, he sets real rules around the concept of wabi ( 侘び ) - i.e. the beauty that lies in the essentiality and simplicity - applied to the performance of the ceremony and the gestures to be performed. The important Zen vision of Wabi Sabi ( 侘寂 ) - which we will have the opportunity to deepen in a next article - is thus consecrated as a pivotal concept, soul, of Cha no Yu.

Chadō, the four founding principles

4 are the principles Rikyū summarizes for the performance of Cha no Yu. They concern both the people who take part in it and the tools used as well as the room itself. Naturally borrowed from Zen aesthetics, they are:

- Wa (和), Harmony. The absence of imbalances or extremism in the interaction between the surrounding environment, things and people. Particular attention is paid to the interaction between guests and landlord: putting guests at ease becomes a pivotal point.

- Kei (敬), Respect. Recognition for the existence of things and people. A sincere soul is necessary: only an open soul will be able to perceive things and people in their true essence (kokoro, 心) and thus enter into authentic communication.

- You are (清), Purity. The absence of attachment to earthly things. Without such purification, true communion with the All is unattainable. It is taken up symbolically from the roji stone path (路地) placed in the gardens outside the tea houses. The variety of shapes and distances between the stones is not by chance designed to educate the guest already from outside to a conscious exercise of attention.

photo credits: iaininjapan.deviantart.com

In a way, the tea ceremony already begins in the garden. Because it helps those who walk this path (a Way) to harmonize with nature even before they set foot in the tea room. The principle is also "evoked" by the symbolic purification of the participants who, once invited to enter by the host, must rinse their mouths and hands.

Jaku (寂), Serenity. The state that is achieved in a natural way by the practice of these three principles already from daily life.

If the hearts of all those present will be open and receptive to the emptiness of that moment if the mind will have left that outside world beyond the garden: a harmony will be born so deep that environment, things and people... will become one. In a perfect fusion where dualism dissolves and it is no longer known where the boundaries of one or the other end or begin.

Chadō, Less is more: beauty according to the Japanese sensibility

In this perspective, negation becomes a positive value, the state of mind par excellence. This is reflected in the research of a frugal style which avoids ostentation and superfluous, already starting from the tea room, the Chashitsu ( 茶室 ).

The latter must be devoid of excessive earthly elements: in the Zen perspective of the master Rikyū it is necessary to limit sensory stimuli as much as possible. Leave space to the void, in order to empty the mind. Then the void itself will give space to the sounds that spontaneously emerge from it and that otherwise too many sensory stimuli would end up eclipsing. Sounds thus assume greater depth and the consciousness is refined. Perception is in fact amplified thanks to silence not only auditory but also visual, olfactory, tactile and gustatory. The senses are literally educated not to be dependent on stimuli, but in this way, they become more receptive. It may seem paradoxical to most people. But if you who are reading have so far understood the sensitivity that underlies this philosophy, you will certainly have understood this too.

The room must, therefore, be minimal, not so much illuminated, "intimate". It must be welcoming. Verbal interactions must be reduced to a minimum, also because non-verbal communication can be done here. Everything is designed in order to create a meditative atmosphere - typical of Zen. It is therefore recommended that we keep our eyes ajar in order to let the images that come into our field of vision flow, avoiding our sense of "feeling" them too much.

The semi-darkness of the room gives back value to the other senses other than sight, usually a little overwhelmed by it. The touch, for example, that emerges in contact with the teacup, in particular, if it is raku ( 楽 ), a symbolic cup in Chadō and Wabi Sabi because of its imperfect shapes that make it unique and unrepeatable. Or, in the case of the traditional Wagashi ( 和菓子, literally "Japanese sweet" ), where the dominant sense would be the taste, we find, on the contrary, also the sight and the other senses involved in a superfine way. But let's dwell on the concept of unrepeatability.

But let's dwell on the concept of unrepeatability.

photo credits: moroalberto.com

Ichi go, Ichi e (一 期 一 会), the metaphor of life

Literally "once, an encounter", Ichi go-Ichi and is a Zen expression that refers to the idea of transience. It reminds us how every single encounter is unique and unrepeatable. Yes, in time we can repeat the ritual of Chadō as many times as we want, but each time remains unique in itself and distinct from the others. The atmosphere experienced in each encounter can never be the same the following times. Therefore, each one of them should be appreciated...as an encounter that happens only once in a lifetime.

So in Chadō, so in life: let go past and future. To take from them the knowledge we need for our learning, yes, but just enough not to get stuck with our minds. Otherwise, we run a risk: that of not appreciating in time the things that are with us here and now. Remaining, in that case, with the regret of not being able to see them in their value (remember the Kei, Respect) when they end their time in our lives.

That is when Zen wisdom comes to us, reminding us that this is the time to focus on, in the here and now, appreciating as much as possible what you have now that you have it. You have to live now and live it, in every single unrepeatable moment. But then again, what is the art of Cha no Yu if not life itself?

Kata - Katachi: When form becomes part of you

In Chadō every gesture is not random: movements and breathing must be harmonized, in order to transmit serenity in giving that cup of tea. You should know that Japanese culture attaches great importance to the concept of form (kata, 型), i.e. gestures codified by certain principles. Not schemes that are an end in themselves but a way to achieve a body-mind-spirit fusion and consequently harmony with existence itself (the concept permeates their vision of the world to such an extent that it also has its own small linguistic form).

When a practitioner arrives at embodying kata to the point that they no longer feel as something external to themselves - to be "staged" - then we speak of katachi ( 形) or "internalized forms". Through kata the practitioner learns patience, precision, resilience...and is forged from them. Final goal: the attainment of harmony with oneself and the surrounding world.

Observe-execute, to the point of internalizing: this is the basic approach of all Japanese art forms-disciplines. It is really part of their soul. They do nothing but decline this feeling in various areas of life. A way of life (the Way) that gives rise to forms of art and discipline which, in turn, guide the individual's path of life. A perfect circle that closes...

But the search for the perfect gesture carries within it another magical gift, that of dilating time. The present moment is crystallized and in that moment the depth of the senses puts us in communion with nature.

But beware: it is not an escape from reality. Sometimes for the human mind, the boundary between the two can be very subtle, but it is a mistake: to shun reality means in truth to alienate oneself from being present. No escape, therefore, as well as no attachment (two extremes of avoiding). But lucid, conscious fusion with what is happening in that place, in that moment. With reality.

The Way of tea, therefore, requires a true psycho-physical discipline about oneself and long preparation. So much so that in the process of self-improvement - as in any self-respecting spiritual discipline - the practitioner can be hindered by the human emergence of feelings such as laziness, apathy or other grey areas.

photo credits: moroalberto.com

The ceremony

The ritual is very complex, especially in its extended form. There is, in fact, a traditional version lasting four hours(!) reserved for formal events (Chaji, 茶事 ) and a reduced version for informal occasions (Chakai, 茶会 ). Likewise, Chashitsu can be distinguished in small (Koma, 小間) or large (Hiroma, 広間). The Koma is the wabi-cha room par excellence, while the Hiroma is well suited to more official circumstances.

During the ceremony, the tea water is boiled in an iron or cast iron teapot. When it is ready, pour some into the ceramic cup where the matcha was previously brought. Then, the whole thing is beaten with a bamboo whisk. The appearance of foam indicates that the tea can be served.

But let's see what happens depending on whether we're in a formal or informal event.

茶事Chaji

- Before tea. Since drinking and eating never go hand in hand, the traditional Kaiseki meal is offered first ( 懐石o会席 ). After the meal, Wagashi are offered at a later stage. Different Wagashi will be paired according to whether the tea is dense or not (as we will see shortly also in the Chakai).

- Usucha. The guests individually drink a whole cup of tea, this time no denser, they dry the edges of it and give it back to the master who in turn washes it, dries it, and prepares it for the next guest.

The ceremony in this form is very elaborate, so breaks and even room changes are envisaged.

photo credits: pinterest.co.kr, pinterest.it

茶会 Chakai

- Before tea. Here the guests receive only the traditional Wagashi sweets, specifically: Higashi (dry sweets) if Usucha is served, Omogashi (soft sweets) if Koicha is served. In any case, the dessert will have to compensate for the bitter taste of the matcha.

- Koicha or Usucha. As the time available is shorter, only one of the two modes can be presented. It will then be up to the teishu (master of ceremonies) to decide which one to perform.

Everything concerning the behaviour to be held or not during the ceremony is called Otemae (お点前). It is known as "etiquette", but it is much more than that. The very way in which the ceremony is carried out right from the preparations (setting up, cleaning and so on) already constitutes the Tea Route. And therefore, the Otemae.

Ways within the Way, Art within Art

The Tea Route is emblematic. For in itself it contains other forms of art that already constitute a world of their own. Other Paths that intersect and unfold in that of Tea creating a unique association where that perfect fusion - mentioned above - is already taking shape. The artisan technique of Raku ceramics, for example, is perfect for embodying the Zen spirit of the Tea Route: in extracting the still incandescent cups from the kiln, it enhances the naturalness of the irregular shapes randomly generated.

The marvellous art of the Wagashi has evolved parallel to Chadō, finding in it its maximum expression. Influenced by the Yin and Yang philosophy and the five elements, its designs and colours inspired by nature and seasons promise an awakening of the five senses. We also include Chakaiseki (茶懐石, Kaiseki kitchen applied to Chadō), Chabana (茶花, Ikebana applied to Chadō), the architecture itself. Even poetry: among the possible verbal interactions there is the possibility for the landlord to quote a Haiku (typical poetic composition) for seasonal reference. They all remind us that things also have a spirit. And that it must be nurtured, respected, contemplated... just like ours.

photo credits: sweetsofjapan.com, Flickr

A universe enclosed in a single cup of tea

The Tea Ceremony is, therefore, a meditative practice to all effects that with the "excuse" of a cup of tea leads us to the doorway of our Consciousness. This intent is at the basis of all Japanese art forms: to use earthly things without being harnessed by them. Knowing how to seek, feel, the spirit within the earthly experience inevitably included in it. The key is not to exclude it, but simply not to be harnessed by it.

As a little girl, I myself did not understand the necessity of having to make all those gestures. Now, after experiencing a particular state of emptiness simply thanks to a pair of chopsticks (hashi), everything became crystal clear to me. Understanding in my heart the loving act of these people, in trying to express this truth. That is why only by experiencing it in person can you truly understand.

As of today, in fact, the main Chadō schools come from the descendants of Sen no Rikyū and are the Omotesenke, the Urasenke and the Mushanokojisenke. They present technical and stylistic differences that however do not affect what is the spirit at the base of Cha no Yu. There are also other minor schools. Among these: the Oribe-ryū descending from Furuta Oribe (successor pupil of Rikyū) and the Yabunouchi-ryū founded instead by such Yabunouchi Kenchū Jōchi who was a disciple of Takeno Jōōō as Sen no Rikyū.

Finally, it is worth mentioning the lesser-known Senchadō (煎茶道), the variant "for infusion" of Cha no Yu, which uses the precious green tea leaves. More recent than Chadō, it is born with a more convivial tone and less "spiritually committed", although it is inspired in several aspects. However, it differs in that it is less rigid and more focused on aesthetic pleasure and fine utensils.

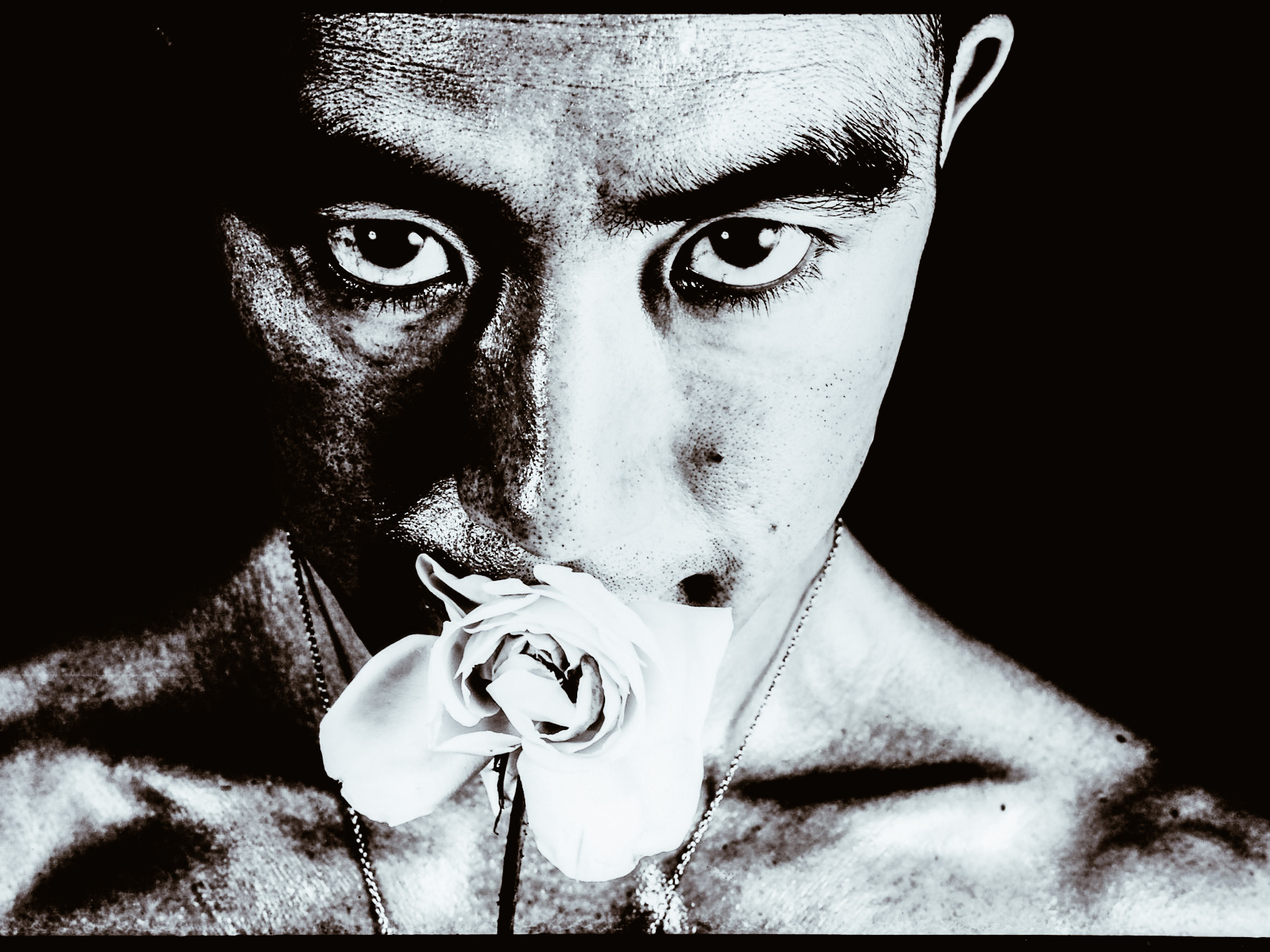

Japan History: Yukio Mishima

Yukio Mishima pseudonym of Kimitake Hiraoka (Tokyo, January 14, 1925 - Tokyo, November 25, 1970), was a Japanese writer, playwright, essayist and poet and this year marks the 50th anniversary of his death.

50 years since Yukio Mishima's death

Author: SaiKaiAngel

photo credits: @williert

Mishima was a highly controversial character, considered close to Fascism in Europe and, according to many critics, a nostalgic Japanese nationalist. Alberto Moravia called him a decadent conservative. The two met in Mishima's Art Nouveau western home in a suburb of Tokyo. Yukio Mishima, on the other hand, called himself apolitical and anti-political. Strongly patriotic, he also inspired numerous characters of his works, and the cult for the Emperor, seen as an abstract and/or semi-divine ideal, the embodiment of the essence of traditional Japan.

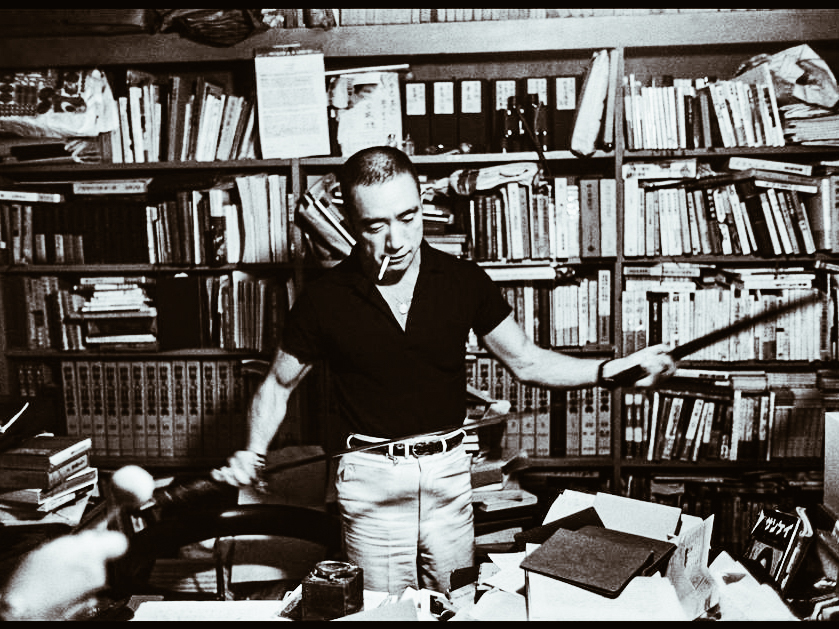

Kimitake Hiraoka was one of the few Japanese authors to have immediate success also abroad. His numerous works range from the real novel to the modernized and readapted forms of traditional Japanese theatre Kabuki and Nō. Yukio Mishima has revisited the Nō theatre in a modern key.

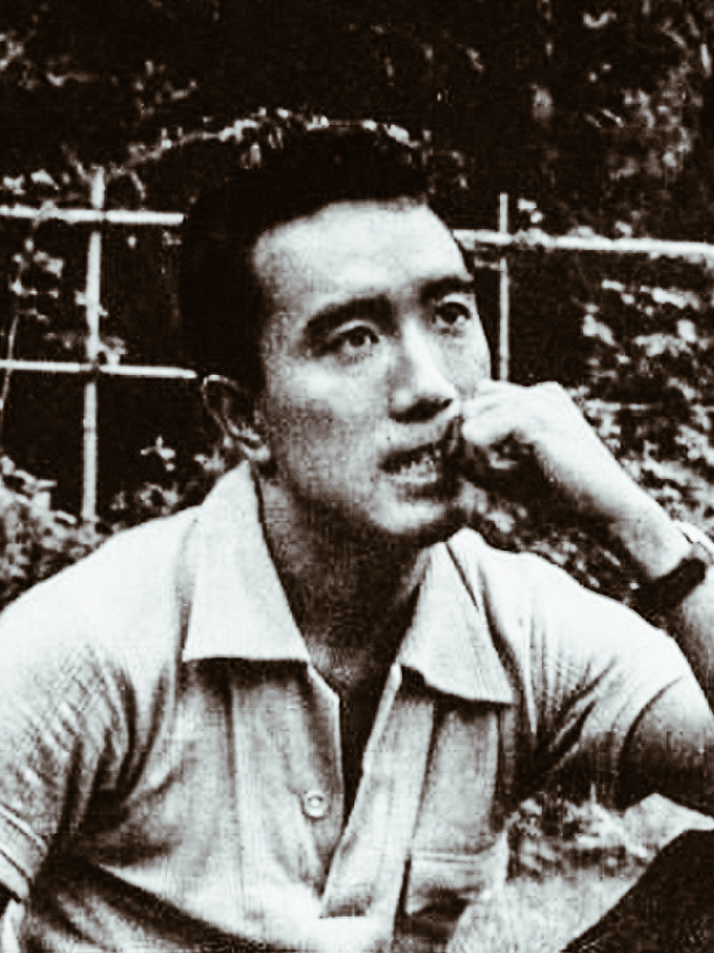

photo credits: thereaderwiki.com

The life of Yukio Mishima

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Yukio Mishima was born in Tokyo on January 14, 1925, in the home of his paternal grandparents, Jotarō Hiraoka and his wife Natsuko. Her parents, Azusa and Shizue, lived together with her grandparents and her grandmother who had an unhappy marriage, assumes all responsibility for the education of the child, usurping the role of the mother. It will be his grandmother to bring the child closer to classical literature and the forms of the theatre Nō and Kabuki.

The relationship that little Kimitake Hiraoka had with her grandmother was something very obsessive, even his mother was allowed to visit him only for breastfeeding.

photo credits: paola1chi.blogspot.com

Grandmother never allowed her grandson to leave the house until Hiraoka escaped from her grandmother stolen from her mother in 1934.

These and other experiences of childhood and adolescence are reported in the novel Confessions of a mask of 1949, in-depth self-analysis of his life.

From 1931 he began studying Gakushūin, the school of the Peers, always thanks to the advice of his grandmother. In this school, most of the students were part of the aristocracy. Those who were not aristocrats were called "outsiders". With this school, students became more warriors than writers and Kimitake Hiraoka's poems were published in the school magazine.

His first work, Hanazakari no Mori (The forest in bloom) was completed in 1941 and was heavily influenced by the Japanese romantic school (Nihon romanha). The professor of Gakushūin letters, Shimizu Fumio, immediately noticed his classical style. Bungei Bunka magazine published the story and from there he began to use the pseudonym Yukio Mishima. Hanazakari no Mori will be published in book form together with other short stories: its success will make the name of the writer known to the public for the first time.

After school, convinced by his father, he enrolled in law university. After graduation, he won a competition as a state official at the Ministry of Finance. During the period of work at the Ministry, he lived a "double life": state official until the evening and writer at night, sleeping no more than three or four hours.

photo credits: oltrelalinea.news

Early works

In 1946 he presented two of his works to the Nobel Prize winner Yasunari Kawabata. Between the two there was a feeling of profound esteem more than that which actually binds teacher and disciple.

In 1948 he began his work at the Kindai Bungaku magazine, linked to leftist circles. Yukio Mishima always tried to avoid any political argument in his novels, apart from the descriptive character that we find in After the feast and the Horses on the run, in fact, Yukio Mishima became part of the leftist group only to get more contacts with the intellectual world.

After the publication of Kamen no Kokuhaku (Confessions of a mask) in June 1949, he received recognition from critics and sales. Between 1950 and 1951 he published three important novels: Thirst for love, The Green Age (1950) and Forbidden Colors (1951). In the novel Thirst for the love he returns to the third-person narrative.

In 1951 he visited the United States, Brazil and Europe as a correspondent for Asahi Shinbun. In Shiosai (The voice of the waves 1954) and the trip to Greece marked the beginning of a new life for Mishima: from 1955 he began to devote himself to bodybuilding, and to kendo.

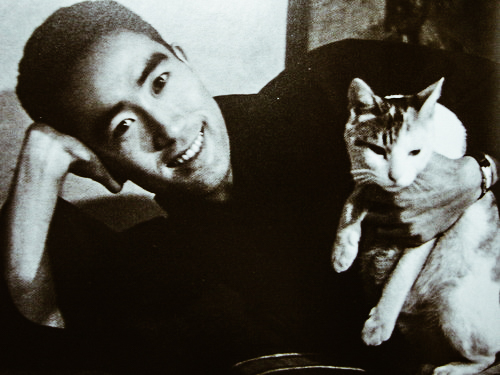

Yukio Mishima: marriage and sexuality

Yukio Mishima got married on 11 June 1958 with Yoko Sugiyama, under the advice of the family; two children were born from the union, Noriko (2 June 1959) and Ichiro (2 May 1962).

photo credits: paola1chi.blogspot.com

Yukio Mishima's sexual orientation was highly controversial, due to some of his visits to Japanese gay bars. Many testimonies saw him as the protagonist of homosexual relationships with for example the writer Jiro Fukushima. The latter wrote a novel describing very explicit details of the relationship with Mishima. At that point, Mishima's children started a fight for violating privacy.

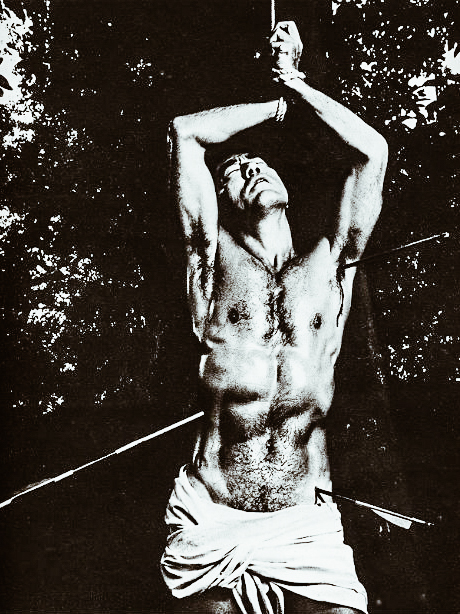

At that time Yukio Mishima entered into a relationship with Eikoh Hosoe and became the model for some of his photos of Bara-kei, 1961–1962. Abroad, the title will be Killed by Roses or Ordeal by Roses.

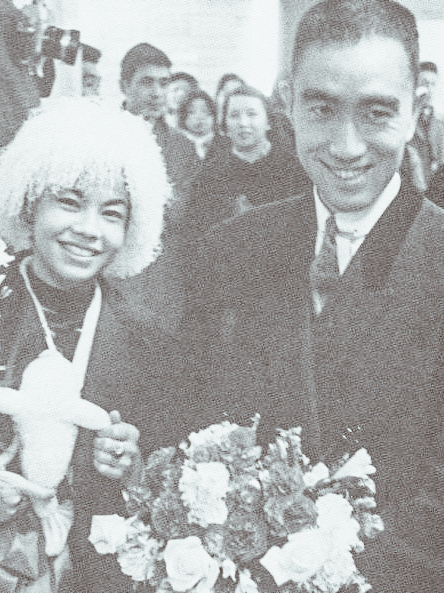

photo credits: dangerousminds.net

He began his acting career in the film based on Yūkoku (Patriotism, 1966), the story of a young officer who decides to do seppuku with his wife. The film was directed, written and played by him. In addition to this, his photos as a bodybuilder and kendōka are published in various newspapers, as well as news of the training periods together with the Jieitai (Japanese Self-Defense Force) and the foundation of the Tate no Kai (Shield Society), his "private army. "

photo credits: lintellettualedissidente.it

The tetralogy Hōjō no Umi (The sea of fertility) began in 1965. The last volume is published in 1970.

Suicide

"A life that suffices to be face to face with death to be scarred and broken, perhaps it is nothing but a fragile glass." (from Spiritual lessons for young samurai and other writings)

Yukio Mishima had always been obsessed with the idea of death and decided to combine this unease with the ideas of traditionalist patriotism.

On November 25, 1970, at 45, Yukio Mishima gathered the most important members of the Tate no Kai ("Association of Shields"), which he himself had found, and occupied the office of General Mashita of the self-defence army. From the balcony of the office, in front of a thousand men of the infantry regiment, as well as newspapers and televisions, he gave his last speech: exaltation of the spirit of Japan, condemnation of the 1947 constitution and the San Francisco treaty, which they made the Japanese national feeling enslaved by westernization.

«We must die to restore Japan's true face! Is it good to have a life so dear to let the spirit die? What army is this that has no more noble values than life? Now we will testify to the existence of a higher value than attachment to life. This value is not freedom! It's not a democracy! It's Japan! It’s Japan, the country of history and traditions that we love. "It was November 25, 1970 in front of an audience of young soldiers, in which after this speech and after praising the Emperor, Yukio Mishima practised seppuku by piercing his belly and then having his head beheaded. Together with him, his most trusted friend and disciple, Masakatsu Morita, committed suicide too.

The choice of Seppuku

The date and manner of killing himself were not random, but chosen as the whole meaning of his life, the purpose for which it had been devoted. It all ended with the extreme act of the Japanese man: seppuku. This sacrifice was based on Wang Yangming's Chinese teaching that "knowing and not acting means not knowing".

Just before seppuku, he had delivered to the publisher the last part of the tetralogy The sea of fertility, which was however completed three months earlier, but with the date "November 25, 1970" just as a testament. He had organized his departure from the scene very coldly, he also left a note: "Human life is short, but I would like to live forever."

The three survivors went to justice and were sentenced to four years in prison for occupying the ministry, but were released for good conduct after a few months.

Summarizing it all, we can say that according to Yukio Mishima the relationships between human beings are reduced to a cloudy and confused mixture of good and evil, of trust and diffidence, distilled in small doses. Despite all this, if the group of people manages to make a pact based on a purity of mind, consumerism, relativism, nihilism and individualism become nothing. Yukio Mishima managed to transform his existence into something more important and profound, thanks to the way he had decided to live and die.

photo credits: wikimedia.org

His works

Romances

The forest in bloom (花 ざ か り の 森 - Hanazakari no mori, 1944)

The doll's house (雛 の 宿 - Hina no yado 1946-1963)

Confessions of a mask (仮 面 の 告白 - Kamen no kokuhaku, 1949)

Thirst for love (愛 の 渇 き - Ai no kawaki, 1950)

The Green Age (青 の 時代 - Ao no jidai, 1950)

Forbidden colours (禁 色 - Kinjiki, 1951)

Midsummer Death (真 夏 の 死 - Manatsu no shi, 1952)

The voice of the waves (潮 騒 - Shiosai, 1954)

A locked room (鍵 の か か る 部屋 - Kagi no kakaru heya, 1954)

Five modern Nō (近代 能 楽 集 - Kindai nōgaku shū, 1956)

The golden pavilion (金 閣 寺 - Kinkakuji, 1956)

A wavering virtue (美 徳 の よ ろ め き - Bitoku no yoromeki, 2007)

Kyōko's house (鏡子 の 家 - Kyōko no Ie, 1959)

After the banquet (宴 の あ と - Utage no ato, 1960)

Animal’s playthings (獣 の 戯 れ - Kemono no tawamure, 1961)

Wonderful star (美 し い 星 - Utsukushii Hoshi, 1962)

The taste of glory (午後 の 曳 航 - Gogo no eiko, 1963)

The school of meat - Nikutai No Gakko, 1963

The sword (1963)

Music (音 楽 - Ongaku, 1965)

Madame de Sade (サ ド 侯爵夫人 - Sado kōshaku fujin, 1965)

The voice of heroic spirits (英 霊 霊 聲 - Eirei no koe, 1966)

Evening dress (夜 会 服 - Yakaifuku), (1966-1967)

My friend Hitler (わ が 友 ヒ ッ ト ラ ー - Waga Tomo Hittorā, 1968)

The sea of fertility (豊 饒 の 海 - Hōjō no umi), 1968-1970, tetralogy composed of:

Spring snow (春 の 雪 - Haru no yuki, 1968)

Horses on the run (奔馬 - Honba, 1969)

The temple of dawn (暁 の 寺 - Akatsuki no tera, 1970)

The mirror of deception (天人 五 衰 - Tennin gosui, 1970)

Middle Ages & The Palace of the Roaring Deer (Mishima, history and secret affairs) (Chūsei, 1945–46 + Rokumeikan 1956)

Essays

1967 - Apollo's cup (ア ポ ロ の 杯 - Aporo no Sakazuki, 1967)

The way of the samurai (葉 隠 入門 - Hagakure nyūmon, 1967)

Sun and steel (太陽 と 鉄 - Taiyō to tetsu, 1970)

1988 - Spiritual lessons for young Samurai (若 き サ ム ラ イ の た め の 精神 講話 - Wakaki Samurai no tameno Seishin kowa, 1970): a collection of essays including the proclamation read by the author a few moments before the ritual suicide.

1997 - Letters 1945-1970 (川端康成 ・ 三島 由 紀 夫 往復 書簡 - Kawabata Yasunari ・ Mishima Yukio Ohfuku Shokan, 1997), SE (ISBN 88-7710-543-7): correspondence between Mishima and Yasunari Kawabata.

Japan History: Maeda Toshiie

Maeda Toshiie was born on January 15 1538 (now Nagoya) as the fourth son of Maeda Toshimasa who held Arako Castle and died on April 27 1599. He was known to be one of the main generals of Oda Nobunaga after the Sengoku period.

Maeda Toshiie, the head of the Maeda clan

Author: SaiKaiAngel

photo credits: wikimedia.org

His father was Maeda Toshimasa and his wife Maeda Matsu. Fourth of seven brothers, his childhood name was "Inuchiyo" and his favourite weapon was a yari, which is why Maeda Toshiie was known as "Yari no Mataza" or Matazaemon. The highest grade he received was that of Great Councilor Dainagon.

By order of Nobunaga, Maeda Toshiie was rewarded with the appointment as the head of the Maeda clan, despite having four older brothers. This position was received in 1560 upon the death of his father. Just like Oda Nobunaga, Toshiie was also a criminal and seems to have become, in his youth, also a friend of Kinoshita Tokichiro, more famous with the name of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. It seems that Toshiie was called Inu (dog) by Nobunaga because of his reserved and severe nature, in contrast to Hideyoshi's talkative nature.

photo credits: samurai-world.com

Military life

Toshiie began his career as a member of akahoro-shū under the personal command of Oda Nobunaga. Later he became an infantry captain (ashigaru taishō) always in the army of Oda Nobunaga. During his military career, Toshiie met many important figures, such as Hashiba Hideyoshi, Sassa Narimasa, Akechi Mitsuhide, Takayama Ukon and many others that we have previously seen in our blog. Maeda Toshiie was also Tokugawa Ieyasu's eternal rival. After defeating the Asakura clan, Maeda fought under Shibata Katsuie in the Hokuriku area.

Maeda Toshiie participated in various war situations: we see him in the battle of Okehazama in 1560 in the siege of Inabayama in 1567, in the battle of Anegawa in 1570, in Nagashino in 1575 and in Tedorigawa in 1577, in the siege of Suemori in 1584 and of Odawara in 1590. Eventually, he was granted the fief of Fuchu and a han (Kaga domain) that crossed the provinces of Noto and Kaga. Despite its small size, Kaga was a highly productive province that would eventually turn into Japan's wealthiest han in the Edo period, with a net worth of 1 million koku.

photo credits: samurai-world.com

Maeda Toshiie had a central group of very capable senior vassals. Some, such as Murai Nagayori and Okumura Nagatomi, maintained a long tradition with the Maeda.

After Nobunaga's assassination in Honnō-ji, Akechi Mitsuhide and Mitsuhide's subsequent defeat of Hideyoshi, Maeda Toshiie fought Hideyoshi under Shibata's command in the battle of Shizugatake. After the defeat of Shibata, Toshiie worked for Hideyoshi and became one of his main generals. Later Maeda Toshiie was forced to fight another of his friends, Sassa Narimasa. Narimasa was shot down by Toshiie following Maeda's great victory in the battle of Suemori Castle. Before he died in 1598, Hideyoshi appointed Maeda Toshiie to the council of the Five Elders to support Toyotomi Hideyori until he was old enough to take control. Despite this, Maeda Toshiie only managed to support Hideyori for a year before he died. Maeda Toshiie's successor was his son Toshinaga.

The Maeda Family

Maeda Toshiie's family played a very important role in her life. His wife, Maeda Matsu, very famous because being an expert in martial arts, was very decisive for Toshiie's rise to success.

Maeda Toshiie's older brother, Maeda Toshihisa, adopted Maeda Toshimasu (more famously by the name Maeda Keiji). Maeda Toshimasu served under Oda Nobunaga together with his uncle. Toshimasu was originally intended to inherit the direction of the Maeda family; however, after Oda Nobunaga replaced Toshihisa with Toshiie as head of the Maeda family, he lost this position. Perhaps because of this loss of inheritance, Toshimasu was well known for the constant quarrels with his uncle Maeda Toshiie.

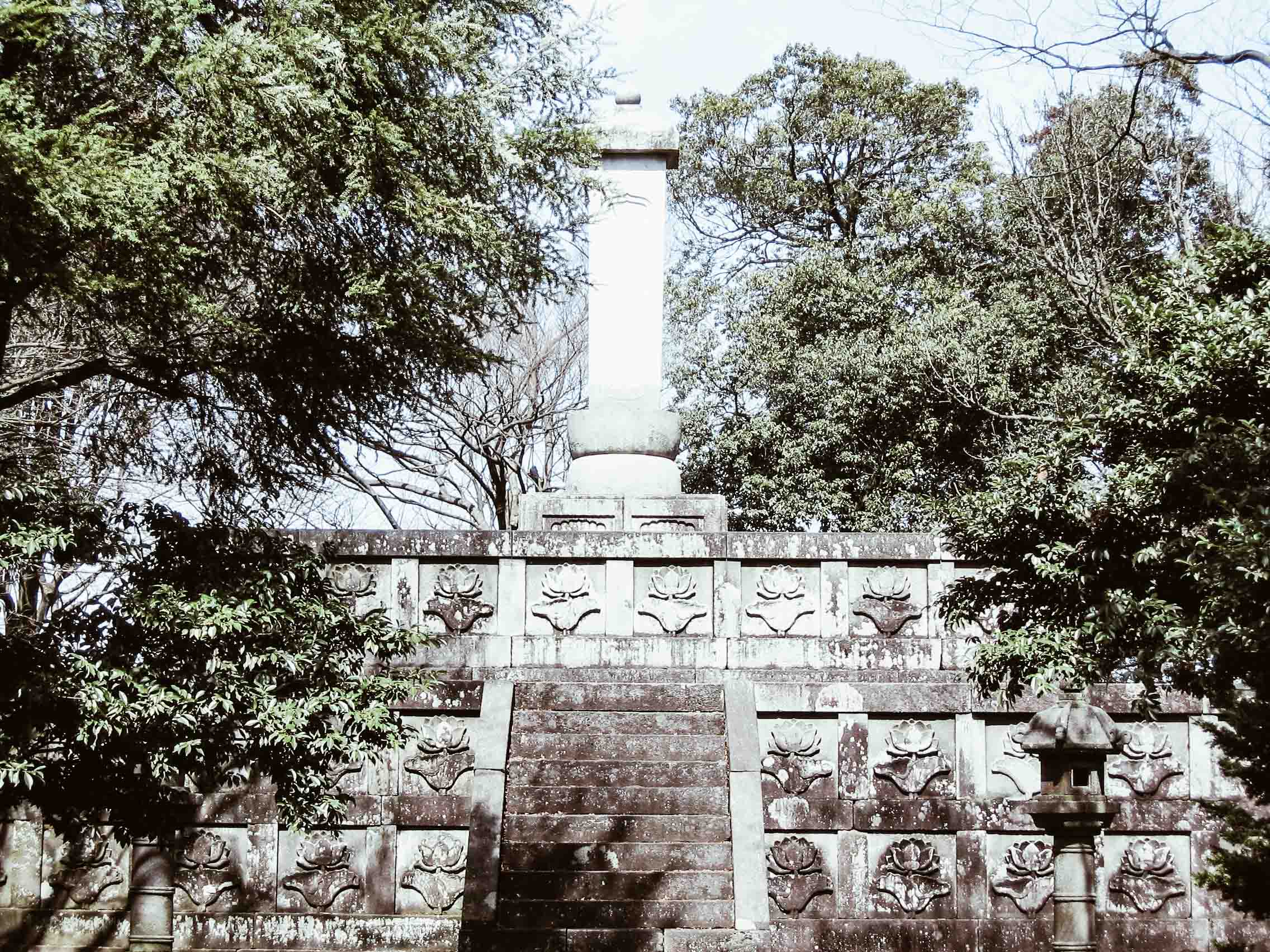

Maeda Toshiie died in 1658 at the age of 64, and her grave is in the Maeda cemetery of Nodayama in Kanazawa.

photo credits: wikimedia.org

photo credits: wikimedia.org

Japan History: Yamamoto Tsunetomo

Yamamoto Tsunetomo, the samurai philosopher

Author: SaiKaiAngel | translation: Erika

Yamamoto Tsunetomo (1659 - 1721), also known by the Buddhist name Yamamoto Jōchō was not only a military man but also a great philosopher. We decided to talk about this Samurai also because of his importance in the literary field.

photo credits: wikipedia.org

The life of Yamamoto Tsunetomo

Samurai of Saga Prefecture in the province of Hizen (Kyūshū), he entered the service of Mitsushige Nabeshima at the age of 9. At the age of 20 he met the Buddhist monk Tannen, who had left the temple in protest of the condemnation of another monk, and Ishida Ittei, a Confucian scholar counselor of Nabeshima who had been exiled for more than 8 years because of his opposition to the decision of a daimyō.

In 1700, at the death of his patron, he did not choose to accompany him in his death with seppuku, because Nabeshima had always condemned that practice, so he decided to continue to respect his will. Yamamoto Tsunetomo decided to take Buddhist vows and take the name Jōchō by retiring to a hermitage in the mountains after some problems with Nabeshima's successor.

After becoming a Buddhist monk of the Zen sect Sōtō, between 1709 and 1716 with his student Tashiro Tsuramoto, he composed the Hagakure, the work on the spirit and the code of conduct of the samurai. Tsunetomo asked the disciple never to publish these thoughts but to set the book on fire, but the young Tsuramoto decided to make it public under the name of Nabeshima Rongo, or "the Nabeshima Dialogues." The book was adopted for centuries as a code of the Samurai and was only printed in 1906 with the title Hagakure ("In the shade of the leaves").

photo credits: amazon.com

Hagakure's main theme is death, not as the end of life, but as the elimination of the ego. Hagakure is a collection of moral principles and advice as behavioral norms and historical news. This book contains some rules of a simple nature, for example "how to dismiss a servant", while others are part of Bushidō, of that set of principles that constituted for centuries the ethics of all Japanese people.

The book written by Yamamoto Tsunetomo, which is originally 11 volumes, has never been fully translated because it is often very specific about Japanese culture to be difficult for Italians to read.

The Hagakure became one of the most famous texts on bushidō around the 1930s.

Some of the most famous phrases in the book

"I have discovered that the Samurai Way is death: you must prepare for death from morning till night, day after day."

"The Samurai Code is to be sought in death. Meditate daily on its ineluctability. Every day, when nothing disturbs our body and our mind, we must imagine ourselves torn by arrows, rifles, spears, and swords, swept by impetuous waves, wrapped in flames in an immense bonfire, electrocuted by a lightning bolt, shaken by an earthquake that leaves no escape, plunged into an endless precipice, agonizing over an illness or ready to commit suicide for the death of our Lord. And every day, unfailingly, we must consider ourselves dead. This is the essence of the Samurai's Code."

"Every morning and every night we should continually think about death, feeling we've been dead forever; in this way, we'll be free to move in any situation."

"We can maintain good relationships with others by giving them the importance and avoiding misunderstandings with good manners and with true humility, doing things well even when they are not useful to us but to others as if it were the first time we meet.

"Those who are impatient end up ruining everything and fail to accomplish great things. Those who do not care about time will complete their mission very quickly."

photo credits: wikipedia.org