Japan History: Date Masamune

Date Masamune

Photo Credits: samurai-archives.com

Date Masamune (伊達 政宗,5 Settembre 5, 1567 – 27 Giugno, 1636) governò durante il periodo Azuchi–Momoyama (ultima fase del periodo Sengoku) e per la prima parte del periodo Edo. Erede di una lunga stirpe di potenti daimyō nella regione di Tōhoku, fondò la città di Sendai. Eccezionale stratega, reso ancora più particolare ed iconico dalla mancanza di un occhio, per questo Masamune era spesso chiamato dokuganryū (独眼竜), o “Il Dragone da un Occhio Solo di Ōshu”.

I primi anni

Date Masamune nacque con il nome di Bontemaru (梵天丸) nel castello di Yonezawa (oggi prefettura di Yamagata). Egli era il figlio maggiore di Date Terumune, signore dell’area Rikuzen di Mutsu, e Yoshihime, figlia di Mogami Yoshimori daimyo della provincia di Dewa. Ricevette il nome di Tojirou (藤次郎) Masamune nel 1578, e l’anno successivo sposò Megohime, figlia di Tamura Kiyoaki, signore del castello di Miharu, nella provincia di Mutsu. All’età di 14 anni, nel 1581, Masamune guidò la sua prima campagna, aiutando suo padre a combattere la famiglia Sōma. Nel 1584, a 17 anni, Masamune ereditò la carica del padre che scelse di ritirarsi dal suo ruolo di daimyō.

L’armata di Masamune era riconoscibile per via dell’armatura nera e l’elmetto dorato. Masamune stesso è conosciuto per alcune caratteristiche che lo hanno fatto risaltare rispetto agli altri daimyō del periodo. In particolare, il suo famoso elmetto con la luna crescente gli valse una spaventosa reputazione.

Da bambino, il vaiolo gli fece perdere la vista all’occhio destro, ma nonostante questo rimane un mistero come abbia perso completamente l’organo. Ci sono varie teorie a riguardo. Alcune fonti dicono che si sia cavato l’occhio da solo quando un membro anziano del clan gli disse che un nemico avrebbe potuto afferrarlo in caso di combattimento. Altri dicono che sia stato il suo fidato servitore Katakura Kojūrō a farlo per lui, cosa che, assieme al suo temperamento aggressivo lo rese il ‘Dragone con un occhio solo di Ōshu’.

La campagna militare

Il clan Date aveva costruito alleanze con i clan vicini grazie ai matrimoni delle precedenti generazioni, ma le dispute locali era comuni. Poco dopo la successione di Masamune nel 1584, un servitore dei Date di nome Ōuchi Sadatsuna fuggì presso il clan Ashina, della regione di Aizu. Masamune dichiarò quindi guerra a Ōuchi e al clan Ashina per questo tradimenimento, cominciando una campagna per dare la caccia a Sadatsuna. Diversi clan anche alleati caddero. Prevedendo la sua sconfitta, nell’inverno del 1585 Hatakeyama Yoshitsugu si arrese a Date. Masamune avrebbe accettato la resa a patto che Hatakeyama gli consegnasse gran parte dei suoi territori. Questo risultò nel rapimento da parte di Yoshitsugu del padre di Masamune, Terumune, durante il loro incontro al castello di Miyamori dove Terumune risiedeva in quel momento. L’incidente finì con la morte di Terumune mentre gli uomini di Hatakeyama in fuga si scontrarono con le truppe di Date vicino al fiume Abukuma.

Seguì una guerra generale tra i Date e gli Hatakeyama sostenuti da Satake, Ashina, Soma ed altri clan locali. Gli alleati marciarono fino a meno di mezzo miglio dal castello Motomiya che era di Masamune, riunendo circa 30.000 soldati per l’attacco. Masamune, avendo solo 7.000 guerrieri, preparò una strategia difensiva facendo affidamento sulla serie di forti che proteggevano le vie di accesso a Motomiya. I combattimenti iniziarono il 17 novembre e non cominciarono bene per Date. Tre dei suoi preziosi forti furono presi e uno dei suoi principali servitori, Moniwa Yoshinao, fu ucciso in un duello con un comandante avversario. I nemici si dirigevano ora verso il fiume Seto, che rappresentava l’ultimo ostacolo tra loro e Motomiya. I Date cercarono di fermarli al ponte Hitadori, ma furono respinti. Masamune portò le sue restanti forze all’interno delle mura di Motomiya e si preparò per quella che sarebbe stata sicuramente una valorosa ma futile ultima resistenza. Ma la mattina dopo, il principale contingente nemico marciò in ritirata. Questi erano gli uomini di Satake Yoshishige. Il loro signore aveva ricevuto la notizia che in sua assenza i Satomi avevano attaccato le sue terre a Hitachi. Apparentemente, questo lasciò gli alleati con meno uomini di quanti credessero possibile per far cadere Motomiya, perché anch’essi si ritirarono entro la fine della giornata.

Probabilmente questa sfiorata sconfitta totale trasformò Masamune nel noto generale che un giorno sarebbe divenuto famoso. Arrivò anche la pace tra Hatakeyama e Soma, anche se questa si dimostrò di breve durata.

Nel 1589, i Date sconfissero i Soma e corruppero un importante servitore degli Ashina, Inawashiro Morikuni, per passare dalla loro parte. Quindi riunirono una potente forza e marciarono dritti verso il quartier generale degli Ashina a Kurokawa. Le forze di Date e Ashina si incontrarono a Suriagehara il 5 giugno. L’esercito di Masamune prese il sopravvento avventandosi contro i vacillanti ranghi degli Ashina, distruggendoli. Infatti, sfortunatamente per gli Ashina, gli uomini di Date avevano distrutto la loro via di fuga, un ponte sul fiume Nitsubashi, e quelli che non annegarono tentando di nuotare verso la salvezza, furono uccisi senza pietà. Alla fine del conflitto, Masamune poteva contare qualcosa come 2.300 teste nemiche, in una delle più sanguinose e decisive battaglie del periodo Sengoku. I ricchi domini appena conquistati ad Aizu divennero la sua base operativa

Questa però sarebbe anche stata l’ultima avventura espansionistica di Date Masamune.

Photo credits: wattention.com

Statua di Date Masamune nella città di Sendai sulle rovine del Castello di Sendai,

Il servizio sotto il comando di Toyotomi Hideyoshi e Tokugawa Ieyasu

Nel 1590, Toyotomi Hideyoshi si impadronì del Castello di Odawara e costrinse i daimyō della regione di Tōhoku a partecipare alla campagna. Nonostante all’inizio Masamune rifiutò l’ordine di Hideyoshi, si accorse presto di non aver altra scelta visto che quest’ultimo era di fatto il dominatore del Giappone. Il ritardo fece però infuriare Hideyoshi. Aspettandosi l’esecuzione, Masamune indossò i suoi migliori abiti mostrando sicurezza nell’affrontare la rabbia del suo signore. Ma Hideyoshi gli risparmiò la vita dicendo “Potrebbe servirmi”.

Ad assedio concluso, Masamune fu costretto a rinunciare ai territori di Aizu e gli furono consegnati Iwatesawa e le terre intorno. Terre che gli avrebbero però fruttato proventi minori. Masamune vi si trasferì nel 1591, ricostruendo il castello rinominato poi Iwadeyama, e incoraggiando la crescita della città sottostante. Masamune rimase all’Iwadeyama per 13 anni e trasformò la regione in un fiorente centro politico ed economico.

Lui e i suoi uomini si distinsero nell’invasione Coreana al servizio di Hideyoshi e, dopo la sua morte, Date cominciò a supportare Tokugawa Ieyasu, sembra sotto consiglio di Katakura Kojūrō. Per questo, Masamune fu premiato con il comando della regione di Sendai, cosa che lo rese uno dei più potenti daimyō del Giappone. Tokugawa aveva promesso a Masamune un dominio che avrebbe fruttato un milione di koku ma, anche dopo i vari miglioramenti, le terre produssero solo 640,000 koku. E molti di questi proventi erano usati per sostenere la regione di Edo. Nel 1604, Masamune, accompagnato da 52,000 vassalli con le loro famiglie, si spostò nel piccolo villaggio di pescatori di Sendai, e lasciò il suo quarto figlio, Date Muneyasu, al comando di Iwadeyama. Masamune avrebbe trasformato Sendai in una grande e prosperosa città.

Nonostante Masamune fosse patrono delle arti e simpatizzasse per le cause straniere, era anche un aggressivo ed ambizioso daimyō. Quando prese per la prima volta il potere nel clan Date, soffrì numerose sconfitte da clan molto influenti come gli Ashina. Queste sconfitte furono causate maggiormente dal suo essere avventato.

Essendo molto potente nel nord del Giappone, Masamune era visto con sospetto. Toyotomi Hideyoshi aveva ridotto le dimensioni delle sue proprietà terriere dopo il suo ritardo nel partecipare all’assedio di Odawara contro Hōjō Ujimasa. In seguito, Tokugawa Ieyasu aumentò nuovamente la dimensione delle sue terre, rimanendo comunque sospettoso riguardo Masamune e la sua politica.

Nonostante i sospetti di Tokugawa Ieyasu ed altri alleati Date, Date Masamune per la maggiorate del tempo servì fedelmente sia Toyotomi che Tokugawa . Prese parte nella campagna di Hideyoshi in Corea, e poi nella campagna di Osaka. Quando Tokugawa Ieyasu fu sul letto di morte, Masamune gli fece visita leggendogli un poema Zen.

Masamune era sicuramente molto rispettato per la sua etica, e un aforisma quotato ancora oggi è “La rettitudine portata all’eccesso si trasforma in rigidità; la benevolenza oltre la misura si riduce a debolezza”

Patrono della Cultura e del Cristianesimo

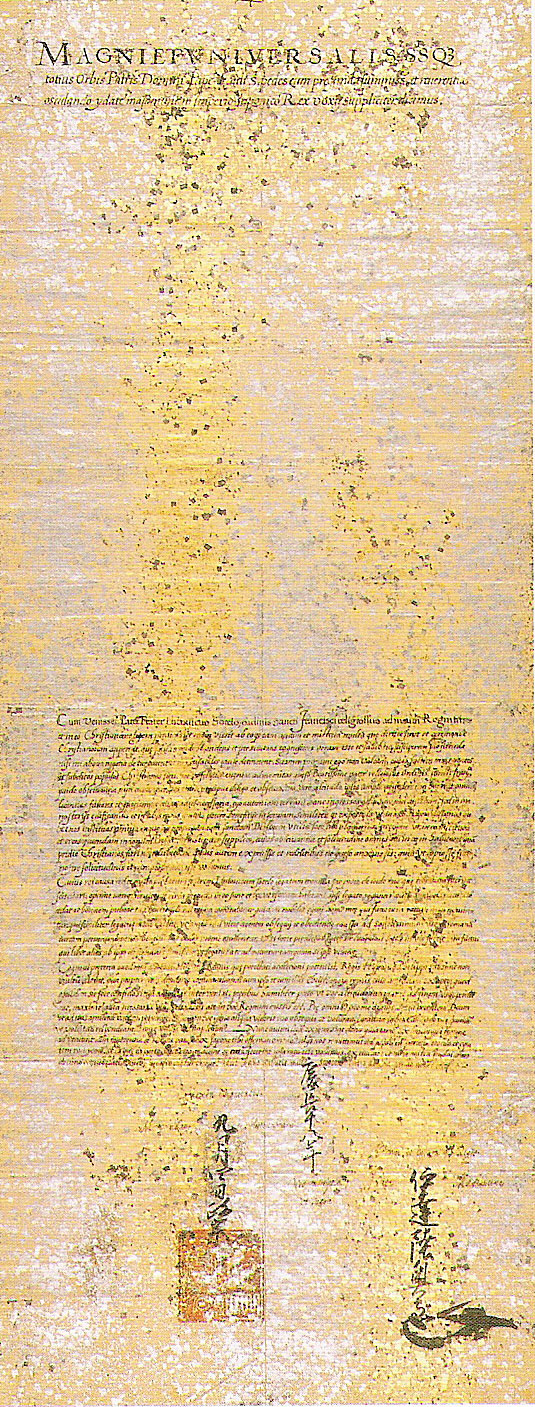

Photo Credits: wikimedia.org

Una lettera scritta da Masamune al Papa Paolo V

Masamune espanse il commercio nella remota regione del Tōhoku. Sebbene inizialmente fu attaccato da clan ostili, riuscì a batterli pur dopo alcune sconfitte. Alla fine riuscì a governare su uno dei più grandi feudi del successivo shogunato Tokugawa. Costruì molti palazzi e lavorò su molti progetti per abbellire la regione. Per 270 anni, il Tōhoku è rimasto un luogo di turismo, commercio e prosperità. Matsushima ad esempio, una serie di minuscole isole, è stata elogiata per la sua bellezza e serenità dal poeta vagabondo scrittore di haiku Matsuo Bashō.

Oltre ad essere noto per aver incoraggiato gli stranieri a recarsi nella sua terra, Masamune mostrò simpatia per i missionari cristiani e i commercianti in Giappone. Oltre a permettere loro di venire a predicare nella sua provincia, liberò anche Padre Sotelo, missionario prigioniero di Tokugawa Ieyasu. Date Masamune permise a Sotelo e ad altri missionari di praticare la loro religione e di ottenere seguaci nel Tōhoku. Inoltre, finanziò e promosse una missione per stabilire relazioni con il Papa a Roma, anche se probabilmente fu motivato almeno in parte da un interesse per la tecnologia straniera. In questo fu molto simile ad altri signori, come Oda Nobunaga. Per la spedizione ordinò la costruzione della nave esplorativa Date Maru o San Juan Bautista, usando tecniche di costruzione navale europee. Sulla nave mandò uno dei suoi servitori, Hasekura Tsunenaga, Sotelo, e un’ambasceria di 180 persone, in un fruttuoso viaggio che comprese luoghi come Filippine, Messico, Spagna e appunto Roma. Prima di allora, i signori giapponesi non avevano mai finanziato imprese del genere, quindi fu probabilmente il primo viaggio di questo tipo. Almeno cinque membri della spedizione rimasero a Coria, in Spagna, per evitare la persecuzione dei cristiani in Giappone. 600 dei loro discendenti, con il cognome Japón, ora vivono in Spagna.

Quando il governo Tokugawa bandì il Cristianesimo, Masamune dovette obbedire alla legge invertendo la sua posizione e, sebbene non gli piacesse, lasciò che Ieyasu perseguitasse i cristiani nei suoi domini. Tuttavia, alcune fonti suggeriscono che la figlia maggiore di Masamune, Irohahime, fosse cristiana.

Photo credits: it.wikipedia.org

Replica del galeone Date Maru, o San Juan Bautista, a Ishinomaki, Giappone

Masamune ebbe 16 figli, due dei quali illegittimi, con sua moglie e sette concubine. Morì nel 1636 all’età di 69 anni. Nell’Ottobre del 1974, la sua tomba fu aperta. Dentro, insieme ai suoi resti, gli archeologi trovarono la sua spada tachi, una cassetta delle lettere con il simbolo di paulownia, e la sua armatura. Dallo studio dei suoi resti, i ricercatori hanno capito che la sua altezza era di 159.4cm, e che B era il suo gruppo sanguigno.

Essendo un leggendario guerriero e leader, Masamune è stato un personaggio di vari drama Giapponesi. E’ stato anche interpretato dal famoso Ken Watanabe nella popolare serie NHK del 1987 Dokuganryū Masamune.

Photo credits: wikimedia.org

La tomba di Masamune al mausoleo di Zuihōden

Condividi:

- Fai clic per condividere su Facebook (Si apre in una nuova finestra)

- Fai clic qui per condividere su Twitter (Si apre in una nuova finestra)

- Fai clic qui per condividere su Tumblr (Si apre in una nuova finestra)

- Fai clic qui per condividere su Pinterest (Si apre in una nuova finestra)

- Fai clic per condividere su Telegram (Si apre in una nuova finestra)

- Fai clic per condividere su WhatsApp (Si apre in una nuova finestra)

- Fai clic qui per condividere su Reddit (Si apre in una nuova finestra)

- Fai clic qui per stampare (Si apre in una nuova finestra)